Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe French Connection

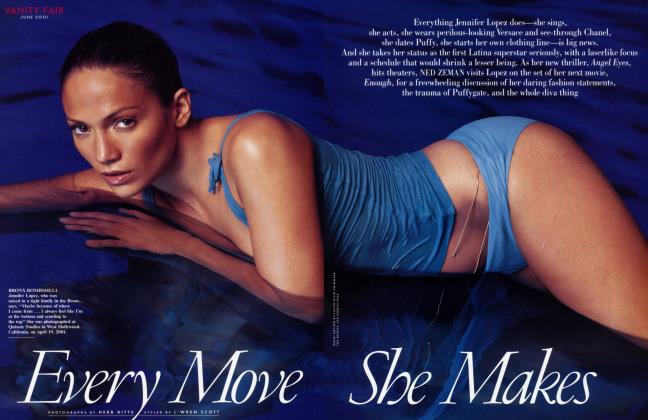

In placing 32-year-old Hedi Slimane at the helm of its men's-wear line, Dior has given Paris fashion the added dazzle of a rising hometown star. Slimane's first Dior collection won t hit stores until later this summer, but the best-connected insiders are already scrambling to get their hands on his elegantly subversive clothes, and Brad Pitt wore Slimane to the altar last year. INGRID SISCHY traces the quiet maverick s ascent, via Yves Saint Laurent, to a commanding position on the Gucci-LVMH chessboard

France doesn't have a monarchy anymore, but the French sure react to Karl Lagerfeld as if he were king. The reception that movie stars get on the streets of Paris is minor compared with what happens when Lagerfeld hits the pavement. Traffic stops. Schoolchildren point. Out come the disposable cameras and the autograph seekers. I witnessed all this and more on a recent spring evening when I was shooting the breeze with the designer and a few others at an outdoor bistro on the corner of Avenue Montaigne and Rue Francois Premier. The best reaction came from a boozed-up old fellow who looked as if he'd been wearing the same clothes since Vichy and who screamed at Lagerfeld, "I love you!"

Only in France can "La Mode" exert such an across-the-board pull. Fashion is a national pastime there, but for some time now the French have been watching outsiders take over their venerable houses—the Englishman John Galliano at Dior, the American Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton, and, most recently, the American Tom Ford at Yves Saint Laurent Rive Gauche—and the nation wants to be proud of a winning home team again. On this score, it just so happened that one of France's great young fashion hopes was also part of the Lagerfeld party that night—the 32-year-old designer Hedi Slimane. He hasn't been top dog at Dior men's wear for even a year yet, but his work for the house is already influential. Slimane is a truly gifted designer who has an utterly contemporary voice and who has, in his first collection for Dior Homme—which hits the stores next month—synthesized the couture tradition and the edgy present. On the one hand, his clothes are beyond beautifully made, with all sorts of luxurious details; on the other, their cut and combination of materials suggest an inner life of more unruly desires. And how many pairs of pants or suit jackets do most of tis own that have a psychological subtext, or that seem to have a soul? Not only is Slimane offering people a new way to dress—women love his men's clothes, too—but along with the 29-year-old Nicolas Ghesquiere, who has recently brought the House of Balenciaga back to life, he has been hailed as a potential savior of French fashion, a Frenchman who "has it in his blood." (He's also received benediction from Hollywood: last July, six months before Slimane had even had his first show for Dior, Brad Pitt wore a sleek black Slimane tux for his wedding to Jennifer Aniston.)

"Hedi is absolutely focused♪he knows where he puts his feet." says Karl Lagerfeld.

But on that recent night when we were all sitting outside, none of the passersby paid Slimane any mind. At first glance he looks like just another young urban hipster. But look again and the Hediness comes out. The alertness in his face gives away his keen awareness and intelligence; his eyes are wide and watchful. His hair tops off his head like a blue jay's crest, and his surname certainly suits him, since he's as slim as a thread. For all his stylish contemporaneity, there is something old-fashioned about his look. He reminds me of one of those intellectual European between-the-wars bohemian figures—Samuel Beckett, say. To Lagerfeld he looks like an actor in a German silent movie, "a cross between Conrad Veidt and Metropolis." You might initially pick up on his obvious shyness, and even his apparent fragility, but under all that is the will of someone who has been put on earth on a mission. As Lagerfeld later told me, "Hedi is absolutely focused—he knows where he puts his feet." And he knows a lot about what is going on in areas outside of fashion, especially contemporary art, architecture, and music, subjects that seem to genuinely interest him and that also subtly inform his work. Most fashion people have an interest in these areas, too, but might not go beyond Julian Schnabel, Frank Gehry, and Patti Smith. Slimane knows every latest development in installation art, in electronic music, and in virtual architecture. It was this precise knowledge that prompted the Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin to award the designer a coveted artist's residency, beginning last year when he was out of work. Now that he's a fashion star, he still spends as much time there as he can, always traveling alone. In fact, you get the feeling he's often alone, even when he's surrounded.

And on that lovely spring night, as I sat beside him watching him watch Lagerfeld handle the crowd—the young master taking in everything—I had the distinct sensation that I was seeing history in the making, one of those moments that crystallize the start of something major. You could feel it, and, along with the season's blossoms, you could practically smell this: fashion is once again in the air in Paris, big-time.

For Paris even to start to matter again in fashion took a while, and Slimane's role in the new course of events is not to be underestimated. (His first name, by the way, is pronounced "Eddy"; his last name rhymes with Iman, as in the model.) Fashion insiders began to pay attention in 1996 when, as a complete unknown, he landed a job as the chief men's-wear designer for Yves Saint Laurent. He took that rather intimidating mandate and managed to be true both to the label and to himself. This was possible because Slimane kept the essence of what Saint Laurent had done—impeccably tailored clothes, always elegant but never stuffy—while rethinking the substance. The new YSL men's wear had lots of black and white, lots of silk, and lots of sheer. It was still suits and long coats, but it looked like nothing that people had seen before because Slimane let his imagination run free. At the time he told a fashion reporter: "I worked with the idea of a guy who goes to a party on the West Coast and has a tuxedo on and suddenly everybody wants to have a swim in the ocean, so he takes off his clothes, and voila—he's wearing this whole matching outfit." The work was a hit, with critics as well as customers.

But shortly after the Gucci Group took over the Yves Saint Laurent ready-towear companies in 1999, Slimane up and quit. The issue seems to have been that Slimane knew he had come far enough along that he needed to be the creative boss, which was not in the picture at the new YSL. There was much talk about where Slimane would go and lots of gossip about the offers he'd received. And when it was announced, three months later, that he had been hired by Gucci's rival, LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton, to basically invent a men's line for Dior, the news was greeted with high expectations. He didn't disappoint with his first collection, last January, and on top of that the show was the catalyst for just the kind of high drama and CapuletMontague symbolism that fashion types eat up. Not only did the mythic Saint Laurent himself, now an employee of the Gucci Group, cross party lines to attend the Dior show, but he and his crowd rose at the end and gave Slimane a standing ovation. This sight fired the imagination of practically everyone who saw it or heard about it, and the tale became instant legend. What would fashion writers do without the rivalry between LVMH and Gucci? God forbid they might even write about the clothes!

In Slimane's case there is much to comment on, though in fact his career in fashion began rather casually. Not very long ago he was just another kid out there with artistic leanings, looking for his place in the world. But right from the beginning he embodied the kind Of Cultural syntheses you can see in his clothes: although he was born in Paris, his father, a retired accountant, is Tunisian, and his mother, a dressmaker, is Italian. (To complicate matters, his mom's mom is Brazilian.) He was raised in a way that emphasized the contrasts in his life, for he not only grew up in the working-class Buttes-Chaumont district of Paris with his own family but also spent a lot of time with the family of a cousin on his mother's side, and she lived in a much tonier way in Switzerland.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 214

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 196

Unlike many contemporary designers, Hedi has had no formal fashion training. What he did have was a mother who loved making her own clothes. The only boy in a family with two daughters, he remembers, "When I was a kid I was always going with my mother to buy fabrics, instead of going to the park." By the time he was 16, the son was also making his own clothes, though he didn't see his pastime as the seed of a career. For one thing, he couldn't afford fashion school, and besides, he told me, he was very serious and found the idea of fashion a bit scary and superficial. "At that time I hadn't met anybody who was so into it that they could make me see it as a very optimistic, positive, inspiring thing," he recalled. He ended up studying art history at the Ecole du Louvre; there he met some kids starting out in fashion whom he could relate to, and whom he soon found himself helping out on various projects.

It was in 1995, while he was pitching in on a show being presented by another young designer, Jose Levy, that Slimane met JeanJacques Picart, a press agent who has been a behind-the-scenes force in the Paris fashion world for years, currently as a consultant for LVMH. Picart became Slimane's "godfather" and saw his future before Hedi himself did; Slimane credits Picart with teaching him that behind the familiar caricatures of the fashion world's exquisite superficiality one can also find true passion, substance, and soul. On a more concrete level, Picart also introduced his young protege to the people at Louis Vuitton, who were embarking on an ambitious and prescient project to examine the idea of the logo and re-invent it. Basically, the underlying question was how to take a classic, traditional company and make it contemporary. Thanks to Picart, Slimane got a job as part of the team—and out of all this he got the perfect experience for what he would be faced with at Saint Laurent.

It didn't take long for the buzz to start after Picart recommended Slimane for the position at the label in 1996. In truth, men's wear at Saint Laurent had been so eclipsed by its couture line and its women's ready-to-wear that Slimane wasn't under that much external pressure—hardly anyone was paying attention. Not that it felt that way to Slimane, then only 27: "I was completely freaked out, because it was this big company with a lot of etiquette, and things worked in a certain way. I was completely out of my parachute, and my first response was to take refuge in the work in the atelier." It paid off. The powers that be, including, of course, the protean Pierre Berge who ran things then, recognized that they had someone special on their hands and encouraged him. They started off by inviting a few fashion journalists and important tastemakers to see what he had done. Bit by bit his presentations got bigger, and quickly word got around that the young designer was someone to watch.

At Dior, with its next-to-nonexistent tradition in men's wear, Slimane was essentially given carte blanche to create the whole shebang, and indeed you can really feel the blank-slate aspect of the enterprise from the minute you arrive at the new headquarters on Rue Francois Premier, which Slimane designed with the technical assistance of the firm Architectes Associes. Overall, the place is like being inside a minimalist light sculpture by James Turrell as furnished by a 21st-century Eileen Gray. (If it sounds rarefied, it is.) This environment is all about reflections and light; surfaces like lacquer and ebony pump the overall effect. The ceiling in the main salon must house the biggest sound system in Paris apart from some stadium somewhere. The furniture, aside from one original Dior chair, was also designed by Slimane.

There's a palpable sense of privilege and secrecy here; to enter, one has to go through doors that can be opened only if one knows the code. That's appropriate, in a way, because Slimane's work is not only about what's visible but also about what isn't. He told me that he doesn't understand the narrative way of creating fashion, which means he stays away from the typical thematic approach, such as clothes inspired by the gangster, the geisha, the peasant, or the Boogie Nights porn star, all of which have figured in recent collections. Instead, he might get turned on by a gesture, by the way someone holds himself, even by an emotion. It is the structure of clothes, the principles of making them, their movement, their rapport with skin, that attract him. Unlike most designers working today, Slimane does not fit his clothes on mannequins. He says he has to try them out on human beings so he can see the movement of the material, the way it folds on the body, and go from there. In fact, his way of designing involves all aspects of the couture tradition as well as the very latest in computer technology; together these approaches allow his clothes to be what they are. Photography is also critical to his process, which partly explains why his clothes are so graphic, and so photogenic. As he continues to work the clothes on his fitting models, Slimane takes pictures of how they look, studies them, and then keeps on refining what he has until he is satisfied. Just how involved Slimane's hand and mind are in each detail of the line is evident with his first collection for Dior. People can't wait to literally get their hands on the stuff—people, that is, who are thin enough to wear them, and rich enough to buy them.

Slimane's are not clothes for big guys like Julian Schnabel or the New York Knicks. What they represent is a way of dressing that brings men's fashion a level of detail and high style that it rarely gets. It is for this reason that women love them, too; Slimane seems to be totally uninvolved with gender cliches. You get the feeling he is designing for a certain type of bodythink aesthete, think poet, think having bigger things on your mind than a hamburger or a bowl of pasta—and he doesn't care what sex it is. (How contemporary!) Typically the clothes are black with a long and lean silhouette. However, they're anything but plain. In his first collection he included leather flowers, leather ribbons, transparent sequins embroidered inside pleats, baroque patterns on laminated sequins, and taffeta—all very discreetly. There was also the occasional shock of color, such as a hot-pink wool-satin sleeveless vest and pants. This is a designer making luxurious-feeling articles of clothing that definitely have a subtext, and that's part of what makes them exciting for people. Exactly what that subtext is is open—which adds a sense of mystery to his fashion. To me, if the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe were alive today, this is what he'd be wearing. Slimane's clothes have all the elegance and polish that Mapplethorpe liked, but also the underlying feeling of sex—with a man or woman—at three o'clock in the morning at some bar along the harbor. Naples, New York, Hamburg, you name it.

It makes sense that most of the time Slimane chooses not the usual fashion haunts, such as Saint-Tropez or St. Barts, but messy old Berlin when he wants to cool out. The city may not seem the most likely of oases, but in fact Berlin is one of the few places right now where there seems to be a lively and authentic art culture, one that, unlike those in New York and London, is not based on money and success. Slimane went there alone after he threw in the towel at Saint Laurent and had no idea what he was going to do next. Now that he's set up as the head of Dior Homme he still goes there whenever he can, staying at his unpretentious quarters at the Kunst-Werke, where his furnishings are pretty much limited to a mattress, a stereo, and old LPs. Hanging out at the institute, he spends his time with artists, musicians, filmmakers, and others who have a more critical approach to culture than those in the fashion world usually do. This is smart of Slimane, because death as a designer comes when one loses one's connections to the real world, or at least a world outside fashion. Slimane is doing everything he can to stay plugged in.

Thinking about Slimane's connection to contemporary Berlin led me to reconnect with the writing of Christopher Isherwood. When I read from the beginning of his A Berlin Diary, which he wrote in 1930 and some of which became the basis for Cabaret, I came immediately to this: "I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking. Recording the man shaving at the window opposite and the woman in the kimono washing her hair. Some day, all this will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed." Hedi Slimane's fashion work is also like a camera— carefully printing, fixing, and creating what a lot of people seem to be yearning for right now.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now