Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

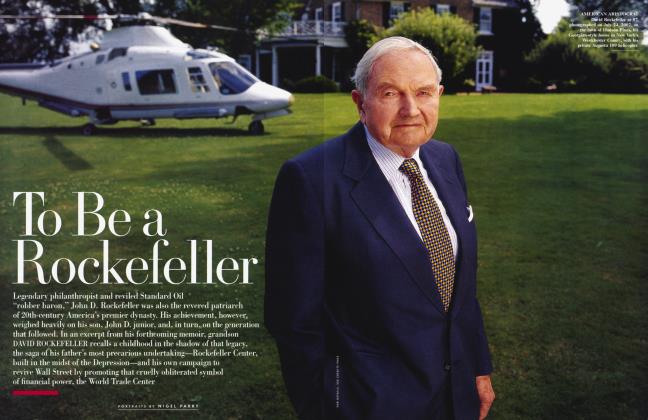

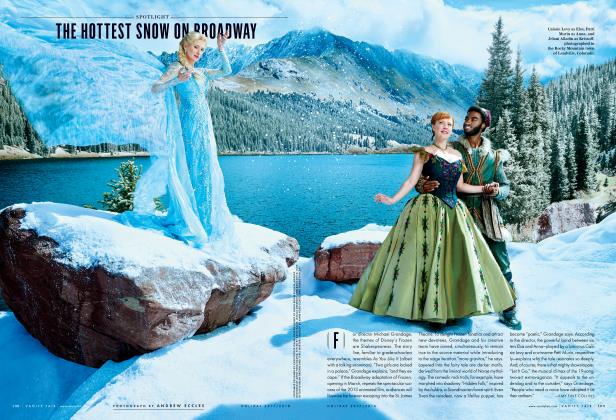

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEloise Takes a Bawth is being published this month, after a 40-year saga during which Eloise's creator, the late, inimitable Kay Thompson, battled with her publisher, her own demons, and the artist who gave Eloise visual life, Hilary Knight. At last, all are invited to the Plaza's madcap aquacade

October 2002 Amy Fine CollinsEloise Takes a Bawth is being published this month, after a 40-year saga during which Eloise's creator, the late, inimitable Kay Thompson, battled with her publisher, her own demons, and the artist who gave Eloise visual life, Hilary Knight. At last, all are invited to the Plaza's madcap aquacade

October 2002 Amy Fine CollinsAround 1947, Kay Thompson—MGM vocal coach, singer, dancer, writer, and allaround grande dame—was running late to meet Hollywood choreographer Bob Alton, who was helping her with a nightclub act. Hell-bent on shortening her route, Thompson impetuously cut through a golf course and drove straight up to Alton's front door. "What's the idea of your being so late?" Alton demanded as she entered. The soignee, 40-ish Thompson offered the only excuse available to her. "I am Eloise," she lisped helplessly. "And I am only six."

That is just one of the several myths of origin concerning Eloise, the fey, hotel-dwelling storybook waif. Thompson's goddaughter Liza Minnelli—who was nine when Kay Thompson's Eloise: A Book for Precocious Grownups leapt onto the best-seller list in 1955—maintains she was the inspiration for the mischievous urchin, "Kay always denied it," says playwright Mart Crowley, a close friend of Thompson's. "For Kay, Eloise was 'me, all me!'" Bea Wain, who sang with Thompson on the radio and appeared with her in the Republic film Manhattan Merry-Go-Round, remembers the entertainer assuming the persona of a naughty little girl as far back as the 1930s. And Thompson's sister Blanche has said that her sibling had been making up a wispy, puerile voice on and off since they were children. "I suppose at some point she simply gave it a name," Crowley says.

Artist Hilary Knight—who illustrated the four classic Eloise books and will be bringing out their long-awaited sequel, Eloise Takes a Bawth (Simon & Schuster), this month—says, "Kay certainly gave her a voice and personality, her own personality, but I invented the image of Eloise. I'd been drawing little girls like her since long before I met Kay." For him, Eloise's aboriginal ancestor is the watercolor of a bushy-haired, saucy girl painted in 1932 by his mother, Katharine Sturges, whose work appeared in The New Yorker and Harper's Bazaar. "It's the way she stands, the palette of black and pink," Knight says. In 1954 fashion editor D. D. Ryan, who had been urging Thompson to transfer her Eloise identity to a more durable medium, introduced the versatile writer to the 28-year-old artist— a galvanizing encounter which led to the birth of their picture book the next year.

'Working with Kay Thompson was fantastic," says Hilary Knight, so much fun that sometimes we had trouble getting started."

In quick succession the fecund pair produced three more Eloise adventures— the cosmopolitan Eloise in Paris (1957), conceived just after Thompson wrapped Funny Face in France (she played Vreelandesque fashion editor Maggie Prescott: "Think pink!"); the bittersweet Eloise at Christmastime (1958), which sold in the hundreds of thousands; and the Cold War period piece Eloise in Moscow (1959). "My technique had fully matured with the Russian drawings—they are my best," Knight says. "In the earlier books, Eloise's appearance was inconsistent—her age and figure change from picture to picture." If anybody ever noticed these imperfections of draftsmanship, they certainly didn't care. By 1963 more than a million copies of the four Eloise books had been sold, and the gamine had generated a merchandising bonanza of toys, clothing, a hit song, and a TV special.

Around 1961, Knight approached Ursula Nordstrom, Harper & Row's revered children's-book editor, about creating a miniaturized boxed set of the four Eloise books for the publishing house's Lilliputian Nutshell Library series. Delighted with the artist's suggestion, Nordstrom asked to meet Thompson. "Ursula, of course, was immediately transfixed by Kay. Kay had an outrageous magnetism, a studied eccentricity. But I had committed one fatal mistake. You could never propose anything to Kay. She always had to suggest something herself. So of course she jettisoned my Nutshell plan right off the bat." But just as quickly Thompson replaced Knight's idea with another, more ambitious scheme of her own—a fifth Eloise book. It was to be titled Eloise Takes a Bawth, and it would be the story of how a long, leisurely soak in the tub leads to a leak that floods the Plaza Hotel. ''Bawth's exact evolution from that First meeting is very hard to pin down," Knight says. "The gestation period was so long. And there were so many interruptions."

Bawth's progress was first thwarted by Thompson's impulsive move in 1962 to Rome, where she took an apartment on the top of the Palazzo Torlonia, near the Spanish Steps. There, Thompson diverted herself with another notion for a picture book, called The Fox and the Fig. Thompson requested that Knight illustrate it, using "a Chinese brush technique," he says. "But I don't work that way." She then asked for Tomi Ungerer. "I think he was too strong a personality for Kay," Knight says. Thompson also sought out Andy Warhol, but Nordstrom found the Pop artist's sample submission to her unsuitably decorative, so he was rejected as well. Thompson discovered her next candidate right in Rome. "I was sharing an apartment there with R. J. [Robert] Wagner," Mart Crowley says. "I was thinking about becoming a set designer. [Crowley went on to write the play The Boys in the Band and for the TV series Hart to Hart.] R.J. was in Rome filming The Condemned of Altona, and seeing Marion Marshall, who became his second wife, and who was divorced from Stanley Donen. Marion and Kay were friends from Funny Face, which, of course, Stanley had directed. Anyway, word got back to Kay about me, and so it was my turn for The Fox and the Fig"—an undertaking that also was eventually left to languish, unfinished.

Inevitably, Thompson's attention circled back to her true love, "me, ELOISE." She summoned Knight to Rome to resume their collaboration. "I spent maybe a month with her in Rome on that initial visit," Knight remembers. "I stayed near Kay at the Hotel Inghilterra, and we would meet every day in the office space she rented in the back of the Palazzo Torlonia, but never before noon. Working with her was fantastic—so much fun that sometimes we had trouble getting started." But when they were ready to get down to business, Thompson was a disciplined taskmaster. While he furiously sketched sheet after sheet, she would compose her lines by "talking them out, rattling them off in Eloise's voice. It was like having some kind of supernatural guidance going on in the background"—a regressive, showbizzy speaking in tongues.

"She was incessantly rewriting," Knight continues, "and her secretaries were constantly retyping. She wore out at least two of them while I was there." Whenever Knight finished a sketch, he says, it would be hung up with paper clips in sequence "on a cotton cord strung across the room," like laundry on a clothesline. Thompson told him, "Think of it as a movie!"

Their sessions were "intense. We'd work straight into the evening. I'd be completely deflated, but then we'd go out to restaurants and eat incredible meals. There was one place that used to fix Kay's pug, Fenice, braised chicken livers. He'd sit on a chair and eat from the table." Afterward, Knight would "fall into bed," while his insomniac partner "stayed up all night revising our work. The next morning I'd Find that she had changed everything completely." To Knight's lasting horror, in his absence Thompson had often smeared his pencil studies with "big globs of rubber cement," to which she then adhered scraps of blank paper. Her intent was to obliterate "everything that had been my invention—not hers." When Knight left for New York they shared the conviction that they had produced all the material required for Bawth. But after gaining some distance they both arrived at the same discouraging conclusion: the book was in fact still raw and unresolved.

The waterlogged hotel has become a communal hydrotherapy tank, and the Venetian Masked Ball is the succès fou of the season.

In the mid-60s, Thompson called Knight back to Rome, where they resumed their writing and drawing marathons as before. But this time the magic between them never quite happened. "Kay was losing control of this property," Knight says. "My drawings were overtaking the book, and that was making her crazy. Here was a woman who excelled at everything—she was a dazzling songwriter, performer, dancer, arranger. The only thing she couldn't do was draw. She really hated that!"

Finally—and anticlimactically—in 1966, Nordstrom received a completed manuscript, and Harper & Row was able to prepare Bawth for publication. Blueprints were dispatched to Thompson in Rome for her approval. The author wasted no time wiring her editor back. Her telegram to Nordstrom read, "This book cannot come out!" Knight recalls, "Ursula was stunned. But Kay was absolutely right to pull the plug on Bawth. My work wasn't any good. It had been labored over for years. Our brains were overtaxed."

In killing Bawth, Thompson discovered a pre-emptive—and hurtful—new way to wield her power. "She found she had the right to take Paris, Moscow, and Christmastime away from the publishers," Knight says. And so she exterminated them too, along with any further commercial ventures. She justified her conduct by insisting that the first Eloise book alone "was perfect," says Knight, "and therefore it all should begin and end there." The artist retained a 30 percent share of royalties from the one title that remained in print, but Thompson owned the copyright to all his Eloise drawings.

Thompson returned to New York permanently around 1967, where for the next seven years the Plaza put her up rent-free. "She came to my apartment," Knight says. "She had totally given up on Bawth. But during this visit—it was 1967—she said, 'Hilary, let's take this book out and look at it again.' And so I started noodling around with a drawing." As he drew, five tapering, pearly fingers descended on Knight's right hand and grasped it. "She took it, and she started pushing it across the page," he says. "She was trying to control my hand totally, make it hers! It was really creepy, an instinct, something she couldn't stop herself from doing. At that instant I knew that I would not, that I could not, work with her again. I told her to find someone else. So she hired an art student who tried to do copies of my work." Nordstrom's letters show that as late as 1969 the editor was still patiently hoping to see a new, finished version of the Bawth manuscript.

Mirroring Eloise's withdrawal from the public, Thompson retreated from the world. She communicated sporadically with only a few friends, mostly by way of telephone. Often over the wire she would revert to the impish voice of her six-yearold alter ego ("Hello, this is me, ELOISE"). She terminated her friendship with Hilary Knight in the 80s—"Kay did not like that I wanted to give Eloise another publicity boost," he says. Thompson filled the void with "paranoid fantasies about Hilary," Crowley says. Infirm and pixilated, she returned obsessively to one delusion, that Knight was "trying to 'take over Eloise."' Thompson died in her mid-90s on July 2, 1998, while occupying Liza Minnelli's East 69th Street apartment. She bequeathed Eloise, her only offspring, to her sister Blanche. With Thompson's stranglehold loosened at last, "everyone wanted to bring back" the three extinct books—Pam, Christmastime, and Moscow—Knight says. "There was a built-in audience dying for them, who'd been waiting for them for decades and decades." Blanche, along with her children John Hurd and Julie Szende, consented to release the three sleeping beauties from the sorceress's spell. Since their 1999 revival about 815,000 of the reprints and their spin-offs {Eloise: The Absolutely Essential Edition; Eloise's Guide to Life; Eloise: The Ultimate Edition) have now been sold, bringing the grand tally of all Eloise books purchased to more than 3.5 million. "These successes spurred the idea of a return to Bawth, " Crowley says.

'If you live long enough," reflects Knight, now 75, "everything comes back around to you. Fortunately, I had saved my Bawth sketches. All the good ones came from that first exhilarating trip to Rome." Attached directly to Knight's sketches by means of the dread "cheap Italian rubber cement" were paper slips with Thompson's typed or handwritten lines of text. Knight called Mart Crowley, a friend since 1968. "Mart had dealt with Kay closely," Knight says. "He knew her sound." The task with which Crowley was presented was essentially "an editorial one," the playwright says. "Kay was like Flaubert—she'd write the same page over and over, changing just one word each time." Over the 1999 Christmas holidays the new team of Knight, Crowley, and Simon & Schuster editor Brenda Bowen conferred at the artist's East Hampton house. "We sat around a table piled with pages," Crowley says. "And we decided together what we loved and what we hated." In the meandering manuscript, "the first material to be cut was anything from which Eloise, the star, was missing." The book that emerged from what Knight refers to as "this 40-year bawth" is supple and effervescent—an Eloise without neurosis. "Well, it is a more elaborate book than Kay and I had ever envisioned," Knight allows. "The fantasy sequences are more prolonged, and there is not much text. This story really moves."

"Eloise is not a bad girl," Hilary Knight explains. She's just an imaginative child.''

Dedicated by Knight to D. D. Ryan, the book opens with a cake of soap swooping out of Eloise's upper-story window—"the first time her room has ever been identified," Knight says. The sudsy projectile is bound for the basin of the Grand Army Plaza's Pulitzer fountain, where a bum contemplates washing himself with it. Meanwhile, in her aerie, Eloise is cleaning herself up to meet the hotel's manager, Mr. Salomone (based on a real-life employee), for tea. As she paddles around her porcelain vessel, she bursts into song, "Oh! I absolutely love taking a bawth." To emphasize her point, she has let the water "gush out and slush" not just from the bathtub's taps but the showerhead and the sink as well. And where is Nanny while the water flows? In one of Knight's illustrations (regrettably discarded by Thompson's estate), she is raptly watching Esther Williams execute her backward-dolphin maneuver in a television broadcast of The Ziegfeld Follies. Later, Nanny tunes in to her favorite, frothiest "soap" operas.

Williams is not the only celebrity who would have been making a cameo appearance at Knight's loopy Plaza. Downstairs in the Grand Ballroom, staff members make preparations for the glitzy Venetian Masked Ball, with gala party entertainment originally to have been provided by the Rhythm Sisters—a girl group composed of Ethel Merman, Lena Horne, Judy Garland, Liza Minnelli, and, naturally, Kay Thompson. (This highcamp conceit was also excised by Thompson's family.) The reader never fully loses sight of Eloise and her ablutive antics, however, thanks to Knight's ingenious split-screen-like device of peeling away the hotel walls (they roll back like scrolls or part like opera curtains).

In Eloise's most vivid daydream, she and a multitude of clones navigate a regatta of sculls, schooners, and speedboats headlong into an enormous wave—the climactic tsunami that inundates the entire hotel. "It all builds up to a big super-sPLAWSH.1" Knight says. While Eloise imagines herself first a mustachioed, cannonball-lobbing pirate, and then a siren undulating undersea, a movie star is squirted with jets of water, spewing from every pseudo-baroque ornament in her suite. Here and there in the drenched hotel, bits of Eloise flotsam can be detected—her hair ribbon, for example, drapes damply over a coiling basement pipe. As Mr. Salomone searches frantically for the origin of the leak, the reader is taken with him on a gatefold tour of the Plaza's labyrinthine plumbing system, delineated by Knight with the mad, vertiginous ingenuity of an architectural engraving by Piranesi. "I decided not to consult any of the technical research I had done 40 years ago," Knight explains, "because I knew it would be funnier if I just made it up." Consequently, the water tank resembles a bathysphere, and the boiler bears a tin-canny resemblance to the potbellied, troublemaking heroine herself.

The source revealed, Salomone charges upstairs to Eloise's room to inform his young tenant, "Thanks to you, the Plaza's through and through / flooded floor to floor / stem to stern / door to door." Yet, unexpectedly—and this is one of the book's strokes of genius—"everyone is thrilled with the water," Knight says. The entire soggy population of the hotel is becalmed; movie stars, waiters, bellhops, bohemians, and debutantes float blissfully like peaceable marine creatures, or else soak up the water like heavenly manna. The waterlogged hotel has become a communal hydrotherapy tank, and the Masked Ball, whose Venetianinspired decor now has acquired a moist authenticity, is the social succès fou of the season.

"Originally, Kay had construed the leak as a disaster," Knight says. "The Plaza's roof caved in, there was panicky live television coverage. Kay had been influenced by J.F.K.'s assassination, which occurred during the course of writing Bawth. At one point, she had even considered dedicating the book to Ethel and Bobby Kennedy."

And is Eloise punished for the aquatic catastrophe? Not at all. "Eloise is not a bad girl," Knight explains. "She's just an imaginative child." Bawth, however, still leaves unanswered one question that has crossed every Eloise fan's mind: Where are the little madcap's parents? Knight says, "My theory is that the father was never mentioned because Kay—you know, she was born Kitty Fink—never mentioned her father," a St. Louis pawnbroker. An alert reader, however, would have found a clue to the mother's whereabouts, if Thompson's heirs had not requested its removal on the eve of Bawth's publication. On one page, on the floor near Nanny's feet, there had been a pad inscribed with a message intimating that the elusive lady has been in Montecatini, the famous Italian spa—deeply immersed, no doubt, in its therapeutic, thermal waters.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now