Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

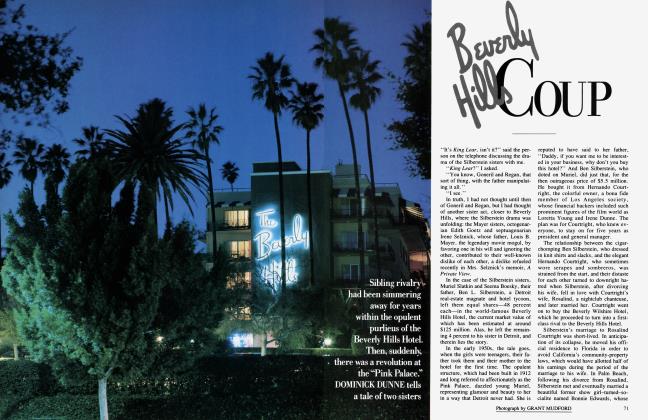

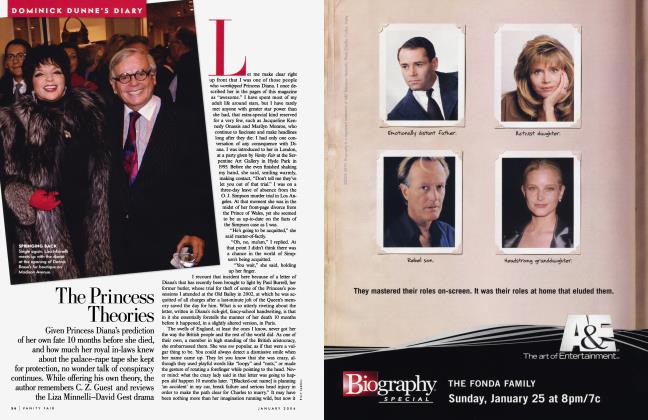

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Menendez brothers and Billionaire Boys Club ringleader Joe Hunt: the author updates his files on some of L.A.’s most notorious recent villains. But he’s also drawn back to the 1970s Begelman forgery scandal and the A-list cover-up that gave him his first taste of crime reporting

April 2002 Dominick Dunne Michael O'NeillThe Menendez brothers and Billionaire Boys Club ringleader Joe Hunt: the author updates his files on some of L.A.’s most notorious recent villains. But he’s also drawn back to the 1970s Begelman forgery scandal and the A-list cover-up that gave him his first taste of crime reporting

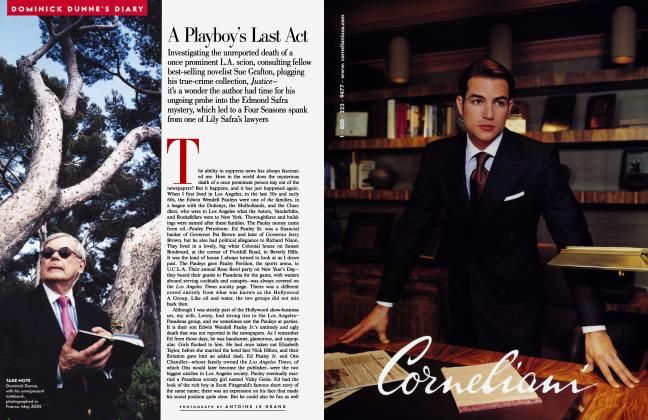

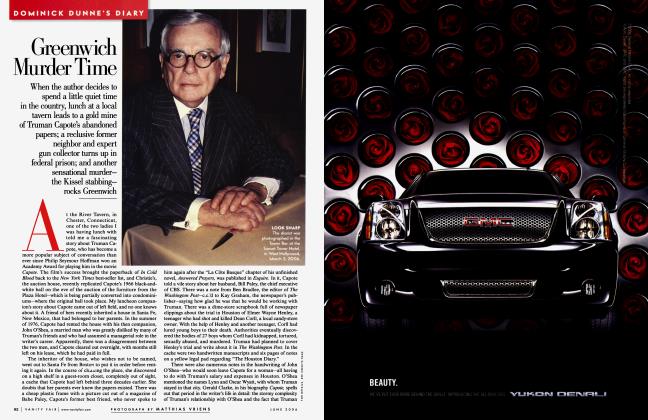

April 2002 Dominick Dunne Michael O'NeillThis being the Hollywood issue, I decided to put some of my favorite topics—the upcoming murder trial of Michael Skakel in Connecticut, the dark doings in Monte Carlo concerning the death of Edmond Safra, the continuing mystery surrounding Chandra Levy’s disappearance—on the back burner and update instead a few West Coast criminal cases before revisiting an old Hollywood forgery scandal in which I played a minor part and which redirected my life’s calling from producing movies to writing books and articles about the rich and powerful in criminal situations. But I do want to mention before it becomes stale news that all the requests for further investigation into Edmond Safra’s death made by his powerful brothers, Joseph and Moise Safra, have been denied by Monaco’s highest court, the Cour de Revision, which provided the brothers with only a video of the reenactment of the night of the penthouse deaths of Safra and his nurse Vivian Torrente. In other words, the investigation is officially closed. Hmmm. Just think about that decision as it applies to Ted Maher. A very upscale, well-dressed man I encountered on Park Avenue the other day called out as he passed by, “That nurse in Monaco is taking the fall, isn’t he?” Next month I hope to be loaded with info on all three cases. But back to L.A.

It looks as if the murder of Mrs. Robert Blake, like that of JonBenet Ramsey, is going to go unsolved, even though everybody feels he knows who’s guilty in both cases. Or so my reporter friend Harvey Levin, who’s producing a new television show called Celebrity Justice, told me when we had dinner at Elaine’s in New York. Harvey is a friend of Robert Blake’s lawyer, Harland Braun. Mrs. Blake, the former Bonny Lee Bakley, who was not a popular woman in anyone’s book, had given birth 11 months before her murder to a baby daughter, Rosie. She was found shot to death in the front seat of her husband’s car, after dining with him in a restaurant they frequented and after Blake returned to the restaurant to retrieve his gun, which he had left behind in the booth, or so he claimed. While I was in Los Angeles over New Year’s, several local news reports announced that an arrest was imminent, although they didn’t say who was to be arrested. It seemed odd to me that anyone would announce an arrest before the arrest, but I was sufficiently tantalized to stay tuned for the next few days; however, no arrest was made and the story died. As everyone knows, Robert Blake was the chief suspect, but the bullets in his gun did not match those in his wife’s body, and although a second gun was later found, there was not sufficient evidence to link him to the crime. Blake, in the meantime, has put his house on the market, and he and baby Rosie have moved in with his older daughter from a previous marriage, who lives in a gated community in the San Fernando Valley.

Several weeks ago I shot the intro for my new television show, Dominick Dunne’s Power, Privilege, and Justice, for an episode about Joe Hunt, the charismatic scholarship student who rounded up a posse of Los Angeles rich kids he had met at the exclusive Harvard School and formed a gang called the Billionaire Boys Club. Hunt had plans to make them all very rich in their own right, but in 1984 he ended up getting involved in two murders. One of his victims was a scary con man named Ron Levin, whom I once knew slightly. He was a mystery man who drove a green Rolls-Royce and gave off an aura of evil. The other was the rich Iranian father of one of the members of the club. Hunt is now doing life in Folsom prison. In the same prison, Erik Menendez, who with his brother, Lyle, purchased two 12-gauge shotguns and blew away their parents in their Beverly Hills mansion in 1989, is doing life without the possibility of parole. Joe Hunt had been a sort of hero to the Menendez brothers. Lester Kuriyama, one of the prosecutors in their trial, which I covered for this magazine, argued that the killer brothers were inspired by a television program about Joe Hunt and the Billionaire Boys Club which they had watched shortly before they slew their parents. Both Joe Hunt and Erik Menendez have married in prison. Lyle Menendez, who is in a different prison, also married, but his untouched bride, Anna Eriksson, divorced him a year later. Joe Hunt married a young woman named Tammy Gandolfo, and Erik married a woman named Tammi Saccoman, a wealthy widow in her late 30s, whose first husband committed suicide. She became fascinated with Erik while watching his murder trial on television in Minnesota. They married in 1999 in a glass-enclosed room at Folsom prison that is usually used by attorneys meeting with their clients. She wore a white pantsuit. Erik was in prison garb. There are no conjugal rights for lifers at Folsom, so they are allowed only to hold hands and exchange quick kisses during visiting hours four days a week. Tammi Menendez owns and operates a pet store called Planet Puppy in the town of Folsom. Tammy Hunt helped her get it started and for a time worked in the shop.

It looks as if the murder of Mrs. Robert Blake is going to go unsolved.

The most puke-making television moment of the month was the Today-show appearance of Mrs. Kenneth Lay, the wife of the disgraced and despised former C.E.O. of Enron, and her flock. Sitting in an elaborately paneled room of her $2.8 million Houston condominium, in the exclusive River Oaks section of town, she cried poor mouth—literally cried, tears and all. “It’s gone. There’s nothing left,” she dared to say, as if she and Ken and the kids were just as bad off economically as all the Enron employees who had lost their life’s savings. She scarcely made mention of the numerous pieces of real estate they were in the process of selling, including one house in Aspen, Colorado, which went for $10 million. Whoever thought that stunt up should get out of the public-relations business. I find it amazing that so many titans are falling these days, deep into the mire of greed.

I love the old scandal stories of Hollywood. I’ve always wanted to write about the Lana Turner/Cheryl Crane/Johnny Stompanato murder case of 1958, inasmuch as it happened just a couple of blocks from where my late wife and I were living in Beverly Hills, and I stood outside Lana’s house for days, watching the comings and goings. It always intrigued me that Lana called her powerful Hollywood lawyer before she called the police, and Jerry Giesler arrived immediately and took care of things. But that story has already been written up wonderfully in this magazine by Patricia Bosworth. There was also the 1932 suicide of Jean Harlow’s brand-new husband, Paul Bern, which might not have been a suicide. Harlow called MGM before she called the police, and Louis B. Mayer, the studio head, and Howard Strickland, the studio’s public-relations genius, arrived and took care of things. There were always people who took care of things back then.

In the 70s, a guy named David Begelman rose to the top in Hollywood. He was an agent who ultimately became the head of Columbia Pictures. Nowadays, nobody outside the film industry knows the names of the studio heads, but the job still had huge importance in Begelman’s time. It catapulted him to the top of the heap of the power structure in the film business. Under his aegis, Columbia released such hit films as Shampoo, Taxi Driver, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. He wore great clothes, drove a Rolls-Royce, and lived in the grand manner. He had charm, wit, a touch of charisma, a kind of glamour, an eye for the ladies, and a rather shady reputation, even before the breaking of the scandal that made him the talk of the town. Allegedly, Begelman had romanced Judy Garland during the beginning of her downward spiral, when she was doing a weekly television show, and, allegedly again, he had skunked her out of a great deal of money, from which poor Garland, who was in love with him, never made a financial recovery. He was suspected of gambling for serious stakes, and of often owing money to men he gambled with. He was the kind of guy who represented everything I had come to hate about Hollywood, but at the same time I was fascinated by him. In fact, I think it’s safe to say that I developed a sort of fixation on him.

Fate put me in his path on many occasions, so I got an up-close lesson in the social behavior of a flawed person putting on a front. He played brilliantly the role of a man who didn’t have a care in the world. Once, at the height of the Begelman scandal, when all anyone in Hollywood talked about was the scandal, Wendy Stark, the daughter of the producer Ray Stark, who was a close friend of Begelman’s, and I were having dinner at the Beverly Hills Hotel, on a banquette in the old swanky dining room that’s not there anymore, and Begelman and Joseph Fischer, the head of the financial department at Columbia, were seated right next to us in an earnest, heads-together conversation. Begelman flashed us his Hollywood, capped-teeth smile, and for the whole dinner Wendy and I had our ears cocked to the next table, trying to hear what they were saying. I was on the skids in those days, but Wendy—who is now a V.F. contributing editor—always stayed a friend, so she was probably paying for dinner that night in such a fancy restaurant. The feeling in the town was that Begelman was going to get away with the crime he had committed.

As crimes go, it was a minor one. It was the cover-up that gave it its importance in Hollywood social history. In 1976, Begelman ordered up from accounting a check for $10,000 made out to the actor Cliff Robertson, whose agent he had once been, before his ascension into C.E.O. circles. He endorsed the check with Robertson’s name, making no attempt to disguise his handwriting, and then took it to the Wells Fargo bank in Beverly Hills, had it initialed by a bank officer, and cashed it for traveler’s checks. He later explained it as expense money for the film Obsession. I always felt he must have gotten a high from the danger of doing what he did. It was not Begelman’s only forgery, though that was not discovered until the Robertson forgery became known. He also forged the name of Pierre Groleau, a maitre d’ at Ma Maison, a restaurant he frequented which was popular with the movie crowd. He had earlier forged a check in the name of Peter Choate, a well-known architect who had designed the projection room in Begelman’s Beverly Hills home. Neither Groleau nor Choate had even been aware that his name had been forged. But Cliff Robertson would be a very different story. Robertson was an old friend of mine, who was then married to Dina Merrill, the actress and daughter of Marjorie Merriweather Post, of the Post cereal fortune. Dina was also an old friend of mine, from live-television days in New York.

Friends advised Cliff Robertson to forget it, but Cliff wasn’t that kind of a guy.

As the head of Columbia Pictures, Begelman was probably one of the highest-salaried men in Hollywood, so $10,000 was nothing to him. He could have called half a dozen friends, any one of whom would have sent over $10,000 by messenger within the hour, but he was a risktaker and liked living on the edge. There was always a mistress in the background in Begelman’s life, and I imagined that a hot-and-heavy matinee must have followed his visit to the bank.

It has never been ascertained why Begelman picked Cliff Robertson’s name for the forgery, or didn’t stop to think that the accounting department of his studio would send Robertson, who lived in New York, a tax statement for $10,000 at the end of the year, a year during which he had not worked at Columbia. Cliff realized that something was up, and he began investigating. He didn’t care that he was dealing with a studio head. Begelman called Robertson and told him that a young man at the studio had forged the check. Lying was second nature to Begelman; he did it effortlessly. Even when confronted with his criminality, he lied.

Friends advised Cliff Robertson to forget it, but Cliff wasn’t that kind of a guy. His name had been forged, and he was going to get to the bottom of things, no matter what. The scandal spread like wildfire. Everybody had a Begelman story to tell. He had never really been accepted by the top movie society, so the whole community was waiting for the story to break in the news, but it didn’t break. The Los Angeles Times virtually ignored a story involving big names and financial malfeasance that was going on right in its own backyard, a story that should have made headlines.

Rumors began that the silence had been imposed on the paper from above. It was well known that for decades the old-line money of Los Angeles and Pasadena had had no truck whatsoever with the A-group society in Hollywood. However, in the early 60s, when Mrs. Norman Chandler, the social powerhouse known as Buff, who was the wife of the owner and publisher of the Los Angeles Times, was raising money to build the Music Center, which would house the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, where the Academy Awards would be held for years, she had to call on Hollywood for financial help. That was the first time the Old Guard and the Hollywood guard ever came together. Now the on-dit was that powers in the film industry had called on Mrs. Chandler to return the favor and have her family’s paper downplay the Begelman scandal.

Well aware of all this intrigue, which I wanted desperately to have exposed, I kept the rumors alive on the telephone. Since I was out of work, I had time to spare. Just then, David Begelman’s wife, Gladyce, a much-beloved figure, brought out a book that was a sort of shopping guide for rich women, which she co-wrote with Fern Kadish and Kathleen Kirtland. It was called New York on $1,000 a Day Before Lunch, and the timing could not have been worse, or better, depending on how you looked at it. There was at that time a flamboyant figure named Allan Carr, who was just beginning to make himself known as a host and personality in Hollywood. For a while he enjoyed a spectacularly successful career as a manager, a promoter, and a film producer. He bought Ingrid Bergman’s old house on Benedict Canyon Lane in Beverly Hills, gave it a Versace look, complete with a mirrored discotheque and a floor lit from below, and threw some of the most notable parties of the 70s. Giving a party for the launch of Gladyce Begelman’s shopping guide was a step up for Allan, and moreover it took the social responsibility off the shoulders of more elevated people. I went to that party. Even though I was in a career downfall, Allan Carr always kept me on his guest list. Hollywood is not a book town, but the power elite of the film and television industry turned out for that book launch. Even such elegant Hollywood ladies as Mrs. Ray Stark and Mrs. Lew Wasserman, who usually didn’t go to parties with a lot of people they didn’t know, turned up. A photographer from Women’s Wear Daily took a picture of me with a joyous Gladyce Begelman, but the paper didn’t print it. Allan Carr was in heaven having such big names as guests in his house. I realized while I was at the party that the whole point of it was to demonstrate solidarity, to show that the power elite were closing ranks to protect one of their own.

The next day I was having lunch in the Polo Lounge of the Beverly Hills Hotel with my then agent, Arnold Stiefel, who was telling me that I was all washed up in Hollywood, which I already knew, but it was tough to have to hear it. It wasn’t a great lunch to begin with. I was telling Arnold about the stellar turnout at Carr’s book party for Gladyce Begelman. I sensed that my agent was ashamed to be seen with me, because I was such a loser. He had an idea for me to write the sequel to a book called The Users, by the gossip columnist Joyce Haber, which she was unable to write after having taken a large advance. All of a sudden, I heard myself being paged, although I hadn’t told anyone that I was going to be there. The bellboy then in the Polo Lounge was a midget, the same midget bellboy, people said, from the Philip Morris commercials during the war, who would cup his hand over his mouth and announce, “Call for Philip Morris.” Anyway, there he was, paging me. I waved my hand to identify myself, and he told me that there was a gentleman in the lobby who wanted to see me. I told him to tell the man to come in, but he said the man didn’t want to do that, so I went out to the lobby. There, in front of the fake fire that was always blazing, was a guy in a trench coat. As I approached, he put out his hand and said, “I’m John Berry of The Washington Post.” It was one of those coincidental meetings that have become a signature of my life. John Berry had been a classmate of my brother Stephen’s at Georgetown University, and he had recognized me because I looked so much like my brother. He told me he had been sent out to cover the long-suppressed forgery story that had such a grip on me. He told me that Dina Merrill had gone to Kay Graham, the then publisher of The Washington Post, and said that a cover-up was going on. The Post had dispatched John Berry and another reporter, Jack Egan, to check out the story. But no one would talk to them, Berry said. Secretaries would not put through their calls. Doors did not open for them. They had not been able to track down anything that would bear out Dina Merrill’s accusation.

In 1995, Begelman shot himself to death at the Century Plaza Hotel.

That meeting turned out to be a life-changing experience for me. Berry was the release I needed to get out the story that was bursting inside me. I didn’t know any inside stuff about Begelman’s aberration, nor had I been at the Wells Fargo bank when he cashed the check, but I knew the unlisted phone numbers of Ray Stark, his close associate at Columbia, and Sue Mengers, then the most powerful woman in Hollywood and a close personal friend of Begelman’s. I also knew that Gladyce Begelman had been so in love with Begelman that she divorced the New York multimillionaire real-estate tycoon Lewis Rudin in order to marry him. I spent a fascinating week with Berry and his partner, driving around with them, watching investigative reporters research and then put together a story. They were among the first to break it nationally, in the Christmas Day edition of The Washington Post. I was thrilled to know that I had played a small part in the process. In 1982, David McClintick wrote the definitive book on the scandal, entitled Indecent Exposure.

Begelman was fired from Columbia, and legal action was taken against him. He was fined $5,000 and ordered to continue sessions with a famous Hollywood psychiatrist named Dr. Judd Marmor. In 1979 he became the head of MGM studios. Cliff Robertson, on the other hand, who had won an Oscar for his performance in Charly, in 1969, never got a role of consequence in Hollywood again. For years Begelman gave screening parties at his house on Sunday nights, showing all the newest films, and the creme de la creme, who had said they would never speak to him again, were all there, accepting his hospitality. As one of Gladyce’s friends said to me, “He sabotaged his marriages and his romances.” In 1995 he shot himself to death in a room at the Century Plaza Hotel, bringing a resolution to the anxieties that must have been on his mind all those years. He had neatly hung up his clothes and taken a shower first, the actress who discovered his body told me.

In the middle of writing this saga of a nearly forgotten Hollywood scandal, I had a phone call. It was from Beth Rudin De Woody, a New York figure prominent in cultural and philanthropic circles, asking me to a small dinner she was giving. Beth is the daughter of Gladyce Begelman and the stepdaughter of the famous forger whom I was at that moment writing about. She said she had just been talking to Annabelle Begelman, David’s widow, whom he married after Gladyce died. Annabelle is also a friend of mine. After David’s suicide, she sent me a Panama hat of his that I had once admired.

I said, “Listen, Beth, there’s something I have to tell you. I’m writing my diary for the Hollywood issue, and they want me to write about another Hollywood scandal. Last year I wrote about Sharon Tate’s murder, and now I’m writing about the, uh, Begelman scandal.”

“Oh dear,” she said. I could tell it was a painful subject for her.

“I played a bit part in that story,” I told her. Once, during the O. J. Simpson trial, David and Annabelle Begelman took me out to dinner with another couple to talk about the trial. I told David that night that I had gotten my start in writing about high-class crime when I helped out the two reporters from The Washington Post. David was so perverse that he roared with laughter.

“Listen, be nice to my mother,” said Beth.

“I loved your mother,” I replied. “Of course I’ll be nice.”

Gladyce Begelman was a class act. She was the most loyal of wives after her husband’s forgery became public knowledge. She held her head high. She continued to go out. Her deportment was a lesson in good behavior for wives of prominent men going through a highly publicized disgrace. She died, much too young, of leukemia. A lot of people who knew her thought that her inner torment had brought on the disease. Pretending that everything is wonderful when it’s not can be a terrible strain.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now