Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAn Upper East side antiques dealer with a tragic past, James Sansum has been charged with stealing half a million dollars in art and books from his former employer, well-known gallery owner Helen Fioratti. In Southampton, the author gets a tip that the case is not what it seems

October 2003 Dominick Dunne SnowdonAn Upper East side antiques dealer with a tragic past, James Sansum has been charged with stealing half a million dollars in art and books from his former employer, well-known gallery owner Helen Fioratti. In Southampton, the author gets a tip that the case is not what it seems

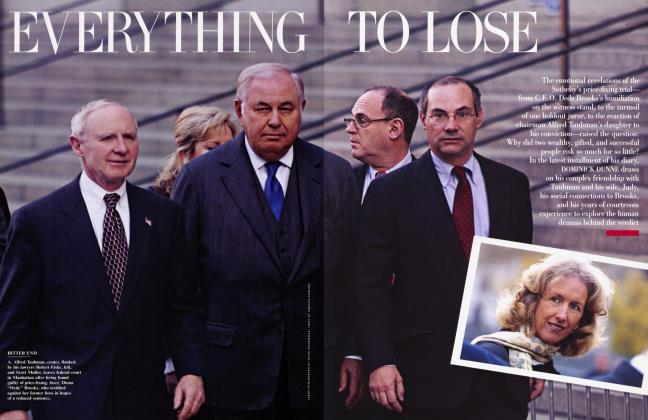

October 2003 Dominick Dunne SnowdonJames Sansum, an antiques dealer on the Upper East Side in Manhattan, is in deep trouble, having been charged with grand larceny and criminal possession of property in the amount of half a million dollars allegedly stolen from his former employer, Helen Fioratti, a well-known figure in the international art market, who has a gallery called L'Antiquaire and the Connoisseur on 73rd Street off Madison venue and who sells to some of the richest people in the world. If convicted, Sansum, who is 36, would face the possibility of 15 years in prison. In a way, it's a very swanky story, although the name James Sansum is relatively unknown outside a small, elite circle. His life has intermingled with those of a number of classy people, but he is a relative newcomer to their world. There now seems be a question in that circle whether the case is a result of a robbery by him or, as Sansum believes, an act of vengeance by her.

I first read about the story in late June in the "Styles" section of the Sunday New York Times, which seemed the right venue for such a rarefied tale. But then a grand lady of exquisite lineage, who wished to remain anonymous, said to me at a lunch party in Southampton over the Fourth of July weekend, "You must write about the James Sansum case. There's more to that story." She silently mouthed the name of an in-the-news C.E.O. under indictment for financial malfeasance. Soon other people I know began to call me about Sansum, all of them expressing the feeling that the whole story was not being told and that he was getting a raw deal. Then Sansum himself wrote me a letter, and after talking with him on the telephone I suggested that we meet in person.

He came to Connecticut and stayed with friends of his in the antiques business who live near me. I already knew that he had gone to Harvard, where he studied medieval-art history, was on the ski team, and became president of the Hasty Pudding Club. In his freshman year he met Arianna Fioratti, Helen's daughter, who was also studying art history. Their response to each other was immediate. They had a brief romance, which developed into a deep friendship. Arianna introduced James to her parents, and over time he became a family member—the son Helen never had, the brother Arianna never had.

Before he came to my house, I also knew something of the dark side of his history. I had heard he was nervous about meeting me. It's always awkward to be interviewed by a stranger and asked personal questions about murder, rape, romance, or, in this case, theft. Sansum is handsome and shy, and he stutters badly, which I could see embarrassed him. Before we started talking, I told him, "We have three things in common. First, I'm an ex-stutterer. I don't stutter anymore, but I know what it feels like when you're fighting to get a word to come out of your mouth. Second, we're both involved in legal cases that are being written up in the newspapers, which is embarrassing for us in front of other people, although I'm not facing 15 years in prison the way you are. Third, we've each had a murder in our immediate families, and you don't meet many people you can say that to." That ended the nervousness.

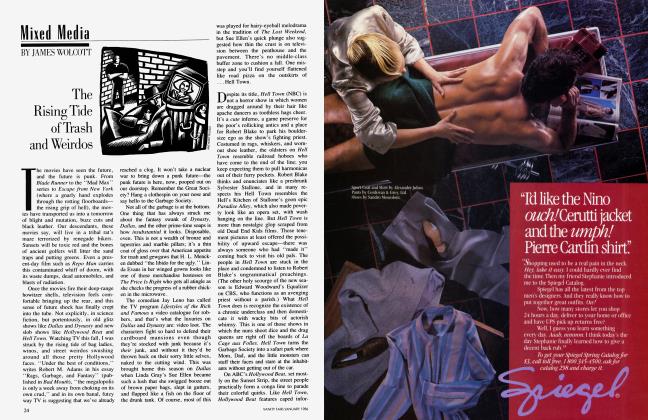

Helen Fioratti accused Sansum of stealing 39 works of art.

When Sansum was 18 years old, his father murdered his mother. The father claimed he had been cleaning an old hunting rifle, which went off by accident. However, there was a girlfriend waiting in the wings, with whom he had been having an affair. She soon moved into the house and married him. James's uncle, his mother's brother, never believed the alibi and pursued the case. The father agreed to give James and his sisters money, but, according to James, "he went back on his word and refused to pay our tuition." James and one of his sisters became convinced that their father had murdered their mother, and 13 years later he was arrested getting off an airplane from Europe. Four years ago, at age 70, he was sentenced to 27 years in prison. James attended the trial, where he was a witness. "He was convicted the 28th or 29th of December 1998," he told me.

"Do you ever visit him?"

"I visited him in the county jail prior to the trial. I don't know where he is serving," said Sansum. Their relationship has permanently ended.

His uncle helped pay his Harvard tuition, and during his junior year he changed his name from Niebauer to Sansum, which was his mother's maiden name. His friendship with Arianna Fioratti was a godsend. When vacations came, and he had no home to go to, Arianna would take him to Florence with her. Her mother, Helen, adored him from the start and took him into the heart of the family. They traveled together. When Arianna married at a castle in Italy, James was a member of the wedding party. Helen and James were interested in the same things—art and furniture. From early on in their relationship, it was understood that when James graduated from Harvard he would go to work at L'Antiquaire.

The gallery took up three floors of a town house, and Fioratti had an apartment made up for Sansum on the fourth floor, which she gave him rent-free as part of his wages. While it was being worked on, he lived in Helen's apartment, at 555 Park Avenue, which looked more like the interior of an Italian castle than a New York apartment. She paid him a salary of only $18,200 a year, less than she paid a maid who worked for her. In time, however, he was given an extra $1,000 a month, not as salary but expense money. She eventually raised that to $2,000 a month and then to $5,000. Among other commissions, Fioratti decorated the palaces of the al-Sabah family in Kuwait. Her husband, who died shortly after Arianna's wedding, gave Sansum 12 shares of L'Antiquaire, out of 200, or 6 percent ownership, worth approximately $400,000. Sansum worked for Helen Fioratti for 12 years.

Then the troubles started. Sansum fell in love with a man, for the first time in his life. The man, whose name was Markham Roberts, is 36, a graduate of Brown University, and a highly respected interior decorator, trained by the late Mark Hampton. In a letter Sansum's lawyer, Michael Lumer, of Montclare & Wachtler, wrote to Assistant District Attorney Robin McCabe, he stated, "There came a time when Mrs. Fioratti learned that Mr. Sansum is gay. She reacted quite poorly, and her treatment and behavior towards Mr. Sansum changed markedly and became increasingly hostile." According to Sansum, it was as if Roberts had upset the applecart in the perfect working arrangement between Sansum and the Fiorattis. After Sansum made plans to live with Markham Roberts in his apartment in Murray Hill, he wrote to Helen Fioratti in Kuwait to say that he wanted to leave the company and cash in his 12 shares. With $400,000, he figured, he would be able to open his own gallery. In October 2001, four months later, when the money was not forthcoming, Sansum filed a civil suit against Helen Fioratti. At eight o'clock one morning in October a year later, in what sounds like a slum drug bust rather than a call on the posh apartment of two upwardly mobile men, there was loud knocking on the door of Roberts's apartment, and someone called out, "Police!" Roberts grabbed a bathrobe, went to the door, and found eight policemen, some with drawn guns. One of them said, "We have a warrant. Are there weapons in the house? Keep your hands up where we can see them."

It was a perfect arrangement for all—too perfect to last.

"I was naked in the bedroom," Sansum told me. "I asked if I could put on my pants. The police watched my hands at all times."

The police took objects and paintings from the apartment. "Those things were mine," said Sansum. "Some of those art books were inscribed to me by professors at Harvard." He was marched through the lobby of his building in front of his neighbors and taken to his gallery, where more armed policemen had gathered.

"How did all that feel, with the police and the guns?," I asked.

"It was worse than when my mother was killed," Sansum replied. "I felt my whole life was crashing down. My whole universe changed. I think it was designed to frighten me, and it did. It was the end of Helen in my life. She was trying to jail me."

Fioratti had accused him of stealing 39 works of art and 294 art books. Her inventory of missing objects was inaccurate, however, according to Sansum. It included, for instance, a 16th-century drawing that had apparently been stolen by a mover when he was in the shop, and Fioratti had made a claim, filed a police report, and collected the insurance money. Other objects she claimed had been missing were reportedly subsequently spotted in her gallery by another decorator. ("We believe that the courthouse is the proper forum to resolve the serious charges prosecutors have leveled against [Sansum]," responds Fioratti's attorney, Michael C. Miller.)

I once interviewed Kate Hepburn—"for 15 minutes only."

Helen Fioratti has a living nightmare in the form of a Dutch writer who calls himself Michel van Rijn—Rembrandt's family name, by the way—on his Web site, where he publishes a paper called Art News. Since the article on Sansum was published in The New York Times, van Rijn has been relentless in attacking Helen Fioratti's integrity and honesty.

But make no mistake about it: Helen Fioratti also has her strong followers, who think she was fleeced. I recently called a rich woman I know in another city—one more who doesn't want her name used—and said, "How are you?"

"I'm absolutely marvelous. I've just had my face and my neck lifted and my tits raised, and I think I look wonderful. I'm 57, after all—it's about time."

"Listen," I said, "is it possible I could have met Helen Fioratti in your apartment in New York?"

"You did meet her. She wasn't at the little dinner you came to, but she was at the large cocktail party, and you talked to her. She's absolutely wonderful. She has a Giotto in her dining room, for God's sake! Why?"

"I'm writing a piece about James Sansum."

"James Sansum! Helen came back from Europe or wherever she was, and she went through all the things in the basement of the gallery, and there were so many things missing!"

Before he left L'Antiquaire, James Sansum made photocopies of deals done by the gallery. At some point, the C.E.O. under indictment mentioned by the grand lady above will reportedly enter this case. This will be an ongoing story.

A. Scott Berg, the Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer of Charles Lindbergh, pulled off the publishing world's best-kept secret, his 20-years-in-the-works remembrance of Katharine Hepburn, entitled Kate Remembered, which was in bookstores within two weeks of the actress's death in Fenwick, Connecticut, at the age of 96. It has been at the top of the New York Times's best-seller list ever since. In the inscription of the copy he sent me, he wrote, "For Nick, who, like the heroine of this book, is no stranger to Hartford, Hollywood, 49th Street, and the Connecticut River, from a longtime friend, Scott." It is true that I have lived in all the places where she lived over the years. I cannot claim to have had a friendship with her, but we had many encounters. Before I bought my house off the Connecticut River, I rented one for two summers in Fenwick, a three-minute walk from her famous white brick house on the beach, which she built after her family's summer cottage there was washed out to sea in the 1938 hurricane. Twice she called and asked me over for tea. She had a cantankerous relationship with her brother Richard, who shared the large house with her, and she would kick him out of the living room before we settled down to chat. Both times she wanted to talk about Hollywood. She knew that I had known her friends David Selznick, George Cukor, and Clifton Webb. I remembered the poem by Kipling that she had read at Selznick's funeral. She loved that. We both lived on 49th Street in New York, and I once interviewed her—"for 15 minutes only"—for a cover story I was writing for Vanity Fair on Warren Beatty, with whom she made her last film appearance, in Loxe Affair in 1994. Her abruptness made me so nervous that I forgot my briefcase when I left. I called to ask if she could leave it with the maid in the kitchen below, and she said no, that I would have to come in and climb the stairs to pick it up where I had left it, so that I would learn not to leave things behind.

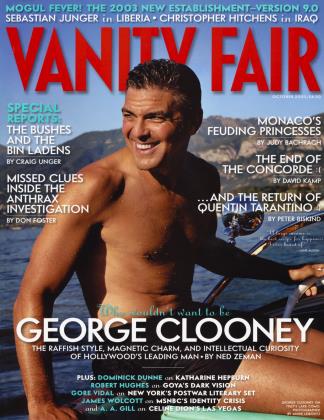

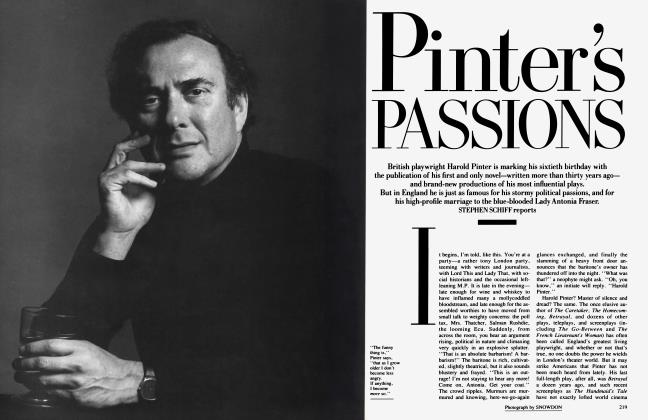

This summer, when I was in London, I received a call at Claridge's, where I was staying, from Lord Snowdon, who had been asked by Vanity Fair to photograph me for this diary. I was due to leave for New York the next day, but on no account was I going to miss an opportunity to be photographed by the great Snowdon.

"When was the last time we saw each other?" he asked over the telephone.

"It was when you were photographing Ava Gardner, and I was interviewing her for the same article in Vanity Fair," I said.

"Good Lord. Ava Gardner's been dead nearly 15 years."

When I got to his studio on Launceston Place at the appointed hour two days later, he had the proof sheets of Ava Gardner out. "It was 1983," he said. We looked at his pictures of that great beauty. "I think it was her last sitting and her last interview," I said.

I sat on a red chair, one of those he had designed, he said, for "the investiture." I assumed he meant the investiture of Prince Charles as the Prince of Wales. He told me he was sad because he had just sold a beloved country house he inherited from his family. He showed me photographs of it in a real-estate brochure. He mentioned a time in the 60s when we had been guests at the Arizona ranch of the late ambassador Lewis Douglas, whose daughter, Sharman, was Princess Margaret's close friend. "Do you remember? Danny Kaye was there," he said. We spoke about Roddy McDowall, who had been a mutual friend. All of these people were dead. Then he talked about his children, and said how proud he was of his son, Viscount Lindley, who has been very successful as a furniture designer. "We talk every day," he said. His daughter by his second marriage, who was a child in the studio the day he photographed Ava Gardner, is now in her 20s, living in Paris and working as an apprentice to an Italian photographer. All during our conversation, he was looking through his lens, giving orders to his assistant, saying, "Move a little to your left," smiling at a good Polaroid, looking cranky at one he didn't like. It was evident that this 72-year-old titled photographer, who once played a romantic role in the history of England's royal family, still loves his work.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now