Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFor 13 years, between 1970 and 1983, I was the principal photographer for Rolling Stone. Everyone called Rolling Stone a music magazine, although most people knew that it was much more than that. I worked with Hunter Thompson on stories about the national elections and Nixon's resignation. I also worked with Tom Wolfe—The Right Stuff came out of Rolling Stone. But music was the center of our lives, or at least it seemed that way.

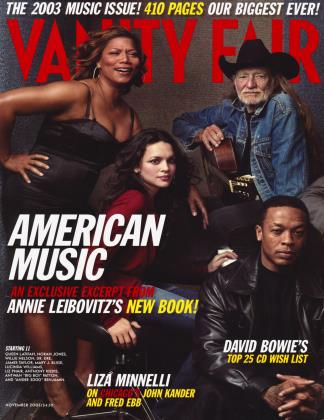

November 2003 Annie LeibovitzFor 13 years, between 1970 and 1983, I was the principal photographer for Rolling Stone. Everyone called Rolling Stone a music magazine, although most people knew that it was much more than that. I worked with Hunter Thompson on stories about the national elections and Nixon's resignation. I also worked with Tom Wolfe—The Right Stuff came out of Rolling Stone. But music was the center of our lives, or at least it seemed that way.

November 2003 Annie Leibovitz

F or 13 years, between 1970 and 1983, I was the principal photographer for Rolling Stone. Everyone called Rolling Stone a music magazine, although most people knew that it was much more than that. I worked with Hunter Thompson on stories about the national elections and Nixon's resignation. I also worked with Tom Wolfe—The Right Stuff came out of Rolling Stone. But music was the center of our lives, or at least it seemed that way.

Before I worked for the magazine, I studied painting at the San Francisco Art Institute and took a night class in photography. The reigning aesthetic was personal reportage—Robert Frank and Cartier-Bresson. It was at the height of the Vietnam War, and soldiers who had come back were attending school on the G.I. Bill. One guy in my photography class—a really, really tough guy—showed us some pictures he'd taken in Vietnam when he was totally stoned. They were of night flares. He was supposed to be holding a gun when the flares went off, but he took these incredible photographs instead.

Rolling Stone hired me after I brought some pictures to the magazine's art director, Robert Kingsbury. There was one of a ladder in an apple orchard that I had taken when I was on a work-study program in Israel, and pictures of people who were living on a kibbutz. I also showed him some photographs I had shot the day before at an anti-war rally. This was not the kind of thing that photographers usually took to Kingsbury. He saw a lot of pictures by people who had gone to concerts and used their cameras to get to the front of the stage. It seemed to me that a concert was the least interesting place to photograph a musician. I was interested in how things got done. I liked rehearsals, back rooms, hotel rooms—almost any place but the stage. And even if I was a fan of someone's music, the photograph came first. It was always about taking the picture. There were other photographers who specialized in shooting musicians—really great photographers. David Gahr, in particular. And Jim Marshall, who probably understood the psyche of a musician better than anyone. He could drink with them and take as many drugs as they did. I couldn't do that without killing myself. But I put in a lot of time with musicians. I had an idea at that point about how musicians lived, but when I went on the road with the Rolling Stones in 1975, I learned how music is made.

That was more than 25 years ago, and I've done a great deal of work since then. I have learned how to help a moment, how to direct it, and when you just have to accept that it's not going to happen and you should come back another day. The impulse to do American Music came from a desire to return to my original subject and look at it with a mature eye. Bring my experience to it. I had something rather ambitious in mind, actually. I wanted to show a Marine marching band, and barbershop quartets, and make it a real American tapestry. It seemed like a good idea to start in the Mississippi Delta, since that's where the music that meant so much to me started. The first person I shot was R. L. Burnside. My crew and I got off the plane and went straight over to his house, which was very dark inside—maybe 10 f-stops different from outside. It was hard to see at first, and then you could make out people sitting in the corners, and tons of grandchildren. Girlfriends. Brothers. Cousins. R. L. Burnside was just sitting around. Life was going on. A woman was putting comrows in one of his nephews' hair.

Nick Rogers, my assistant, and Karen Mulligan, my producer, are very friendly people, and when we showed up it was like an instant party. Not like the old days, when it was just me and my camera. We helped things along by asking Burnside if he would mind playing the guitar. He pulled a lot of stuff out of his garage and someone set up some drums and they played in the carport. I got many beautiful pictures from that first encounter.

The trips to the Delta didn't feel like work. I didn't have to hope that something would happen. Stuff was happening. In Clinton, a little town not far from Burnside's house, we were working with Eddie Cotton Jr. in a club, and while we were setting up the lights I went outside and he was sitting in a car with a girl. I took the picture that we used in the book. We talked about shooting the next day, which was Sunday, and he said that he couldn't get together until later in the afternoon, because he played the organ in his dad's church. I met him there and took some pictures in the church, and then we were standing on the sidewalk and a little girl walked by, looking pretty in her Sunday clothes. I asked Eddie if he knew her, and he laughed and said, "Annie, everyone here is related to everyone else." She was his cousin. We used that photograph, too.

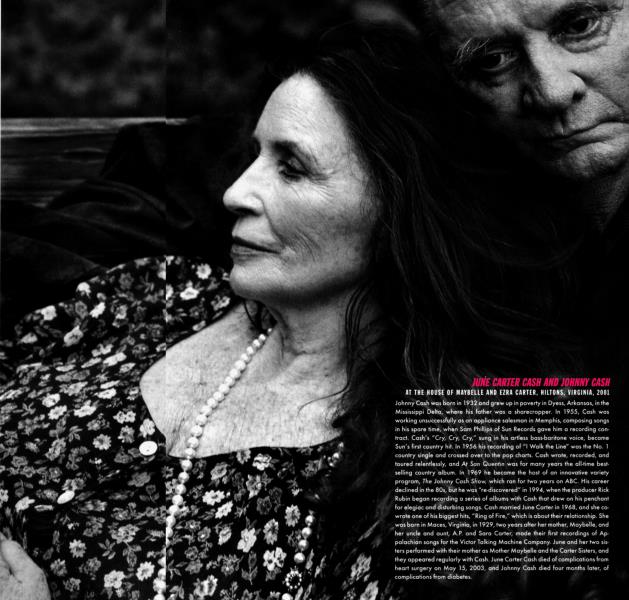

I wanted to photograph Rosanne Cash with her father, Johnny Cash. He had not been well, but he organized a family reunion and birthday celebration for his wife, June Carter Cash, in Hiltons, Virginia, where the original Carter-family homes are, and they invited us to come. It turned out to be the last big gathering of the clan before June's death. We ate with them, and they included us in everything. We shot some photographs at a picnic, and Rosanne and her father sat on the front porch of June's parents' house, and Rosanne played guitar and sang.

I always try to take pictures in places that mean something. The Carter-family porch means a great deal. Several generations of the family sat on that porch. It's not just any porch—I was looking for that kind of detail. A room. Or a chair. One afternoon I went to a juke joint that someone had told me about, thinking that I would like to get a dancing picture. The juke joint was in the middle of a field, and it looked pretty much the way it did a hundred years ago, except for the fact that there was a Lincoln parked in the garage. We knocked on the door, but no one was there, and we were sitting around waiting for somebody to come down the road when I realized that the house was the picture. It was a kind of window on the subject.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers were photographed on the lawn at Fisk University, in Nashville, because I thought you should see the campus and the trees. But then a couple of years later we heard they were performing in New York and we asked them to come to the studio and sing. And when they did I just started to cry, it was so powerful. They weren't belting it out or anything. They were very controlled. But I was totally unprepared for the beauty their voices made in union. I had asked them to come to the studio because I wanted to photograph what singing looks like. I guess I had in the back of my mind Richard Avedon's photograph of Marian Anderson singing. I wanted to see the song. I tried to do this several times. When we went to photograph Ralph Stanley, I asked him to sing "O Death," the song that he won a Grammy for when it was on the soundtrack of O Brother, Where Art Thou? I thought, Well, this will be great. He has this weathered, worn face, and he'll be singing about death. I thought I would have a photograph of a man wailing. But he started to sing and his mouth was hardly open and his teeth were clenched. Which, I realized, made sense. You aren't going to sing, "Hooray, here's death." He sang the whole song all the way through, and his mouth was open maybe a quarter of an inch.

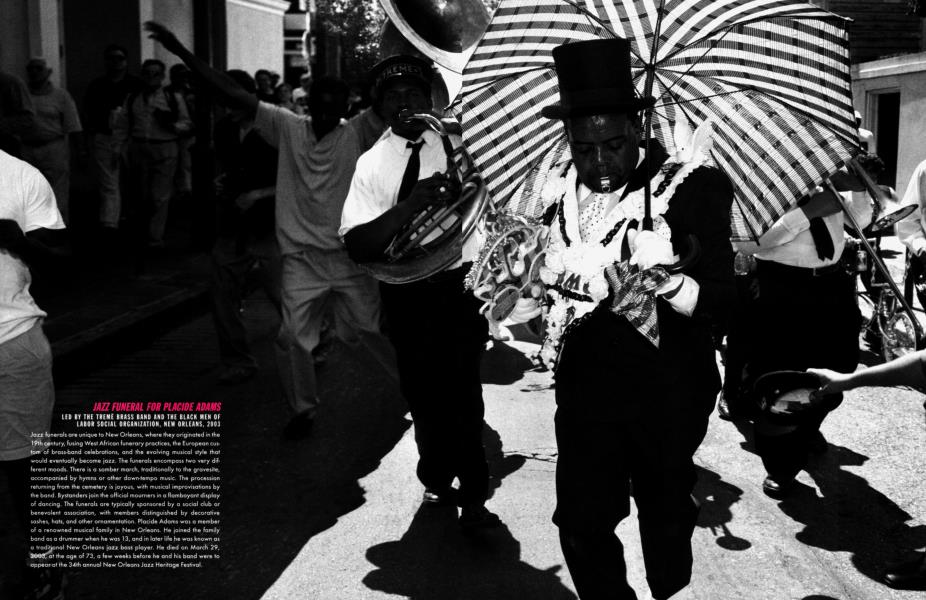

I often got something other than what I had anticipated on this project. Something else. Something that moved me unexpectedly. The musicians who played at Placide Adams's funeral in New Orleans, for instance. Their horns were battered and beaten up, and they were so poor that they barely had shoes, but when the procession started, the music was so rich and so great that I was walking down the street with my camera, crying. I felt privileged to be able to listen to these people play.

Etta James was born Jamesetta Hawkins in Los Angeles in 1938 to a teen mother. She began singing in a Baptist church choir when she was 5 and at 15 came to the attention of the bandleader Johnny Otis, who in 1953 took her and two friends into a studio to record "Roll with Me Henry," a response to Hank Ballard's R&B hit "Work with Me Annie." The song was retitled "Wallflower" and became a Top 10 R&B hit. Otis gave her the name Etta James, and she became one of the most popular members of his show. In 1960 she signed a contract with Chess Records in Chicago and soon became an R&B superstar. But James was beset by personal problems (including heroin addiction and a series of abusive lovers), which she discussed frankly in her 1995 autobiography, Rage to Survive. Her career gained new momentum after she opened for the Rolling Stones on their 1981 U.S. tour. She was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1993 and received a Lifetime Achievement Award at this year's Grammy ceremony.

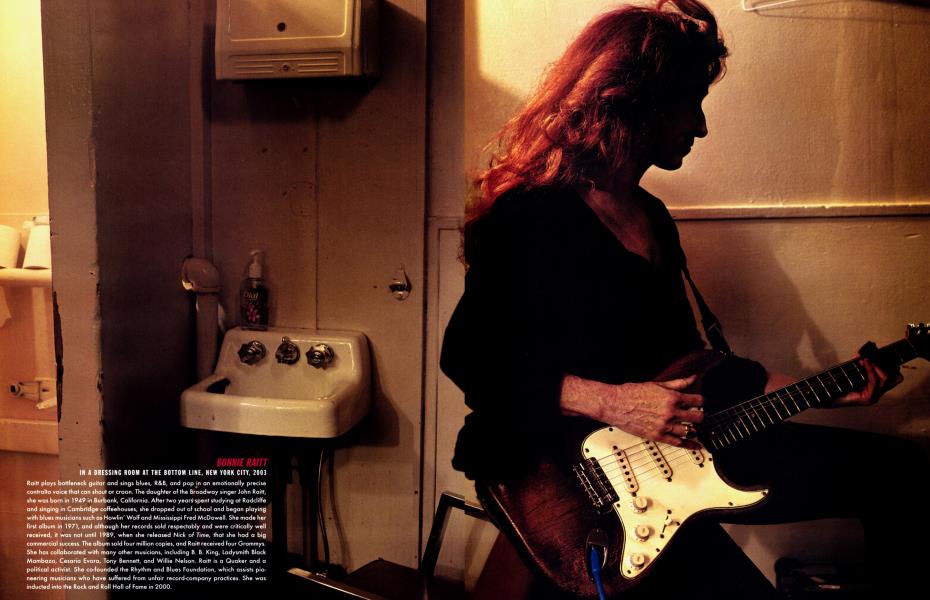

Raitt plays bottleneck guitar and sings blues, R&B, and pop in an emotionally precise contralto voice that can shout or croon. The daughter of the Broadway singer John Raitt, she was born in 1949 in Burbank, California. After two years spent studying at Radcliffe and singing in Cambridge coffeehouses, she dropped out of school and began playing with blues musicians such as Howlin' Wolf and Mississippi Fred McDowell. She made her first album in 1971, and although her records sold respectably and were critically well received, it was not until 1989, when she released Nick of Time, that she had a big commercial success. The album sold four million copies, and Raitt received four Grammys. She has collaborated with many other musicians, including B. B. King, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Cesaria Evora, Tony Bennett, and Willie Nelson. Raitt is a Quaker and a political activist. She co-founded the Rhythm and Blues Foundation, which assists pioneering musicians who have suffered from unfair record-company practices. She was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2000.

Sumlin was born in 1931 in Greenwood, Mississippi, the youngest of 13 children. He began playing guitar in clubs when he was 12. In 1954 he joined Howlin' Wolf's band in Chicago and, at Wolf's request, developed a unique fingerpicking technique. Many of their classic recordings together, including "Back Door Man" and "Little Red Rooster," have been covered by such artists as the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, and the Doors. Sumlfn retired for a time after Howlin' Wolf died in 1976, but returned to music in the 80s. Willie "Pinetop" Perkins was bolt) in Belzoni, Mississippi, in 1913. He began his career as a guitarist, but was forced to change instruments after being stabbed in the arm. He became a pianist, played for several years with Sonny Boy Williamson, and later worked with B. B. King. In 1969 he replaced Otis Spann in Muddy Waters's band. In 1998, Perkins and Sumlin recorded Legends, a mix of traditional Delta blues and electric-guitar-based rock, which was nominated for a Grammy. Perkins was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame this year.

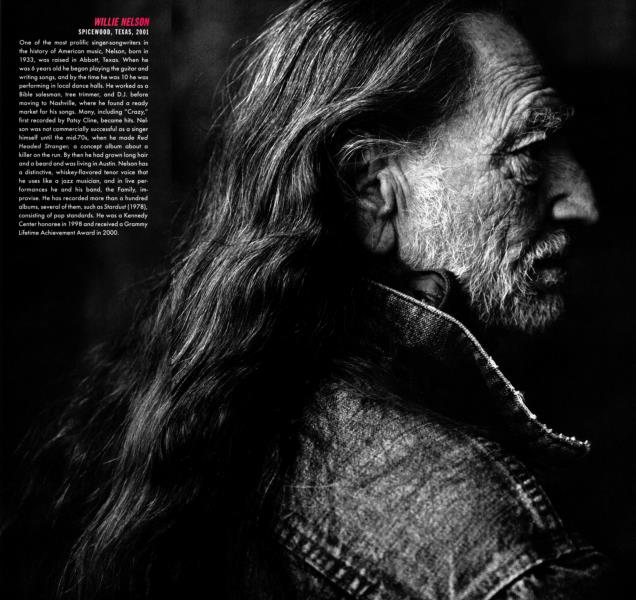

One of the most prolific singer-songwriters in the history of American music, Nelson, born in 1933, was raised in Abbott, Texas. When he was 6 years old he began playing the guitar and writing songs, and by the time he was 10 he was performing in local dance halls. He worked as a Bible salesman, tree trimmer, and D.J. before moving to Nashville, where he found a ready market for his songs. Many, including "Crazy," first recorded by Patsy Cline, became hits. Nelson was not commercially successful as a singer himself until the mid-70s, when he made Red Headed Stranger, a concept album about a killer on the run. By then he had grown long hair and a beard and was living in Austin. Nelson has a distinctive, whiskey-flavored tenor voice that he uses like a jazz musician, and in live performances he and his band, the Family, improvise. He has recorded more than a hundred albums, several of them, such as Stardust (1978), consisting of pop standards. He was a Kennedy Center honoree in 1998 and received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2000.

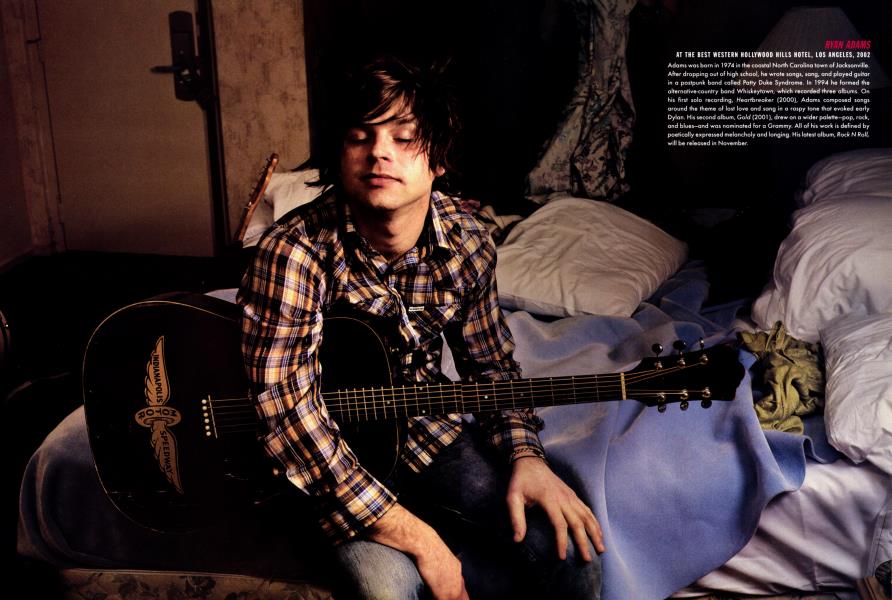

Adams was born in 1974 in the coastal North Carolina town of Jacksonville. After dropping out of high school, he wrote songs, sang, and played guitar in a post-punk band called Patty Duke Syndrome. In 1994 he formed the alternative-country band Whiskeytown, which recorded three albums. On his first solo recording, Heartbreaker (2000), Adams composed songs around the theme of lost love and sang in a raspy tone that evoked early Dylan. His second album, Gold (2001), drew on a wider palette—pop, rock, and blues—and was nominated for a Grammy. All of his work is defined by poetically expressed melancholy and longing. His latest album, Rock N Roll, will be released in November.

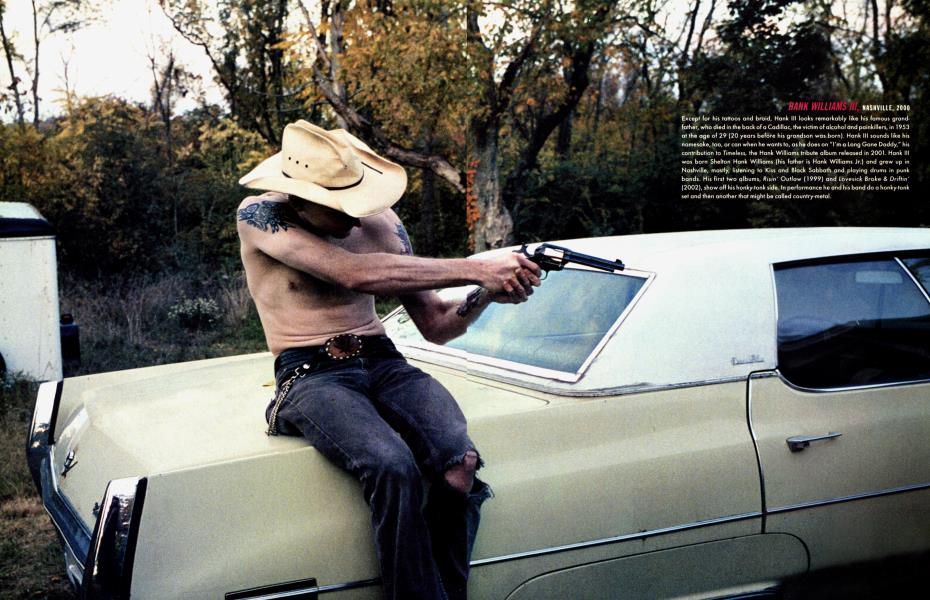

Except for his tattoos and braid, Hank III looks remarkably like his famous grandfather, who died in the back of a Cadillac, the victim of alcohol and painkillers, in 1953 at the age of 29 (20 years before his grandson was born). Hank III sounds like his namesake, too, or can when he wants to, as he does on "I'm a Long Gone Daddy," his contribution to Timeless, the Hank Williams tribute album released in 2001. Hank III was born Shelton Hank Williams (his father is Hank Williams Jr.) and grew up in Nashville, mostly, listening to Kiss and Black Sabbath and playing drums in punk bands. His first two albums, Risin' Outlaw (1999) and Lovesick Broke & Driftin' (2002), show off his honky-tonk side. In performance he and his band do a honky-tonk set and then another that might be called country-metal.

Johnny Cash was born in 1932 and grew up in poverty in Dyess, Arkansas, in the Mississippi Delta, where his father was a sharecropper. In 1955, Cash was working unsuccessfully as an appliance salesman in Memphis, composing songs in his spare time, when Sam Phillips of Sun Records gave him a recording contract. Cash's "Cry, Cry, Cry," sung in his artless bass-baritone voice, became Sun's first country hit. In 1956 his recording of "I Walk the Line" was the No. 1 country single and crossed over to the pop charts. Cash wrote, recorded, and toured relentlessly, and At San Quentin was for many years the all-time bestselling country album. In 1969 he became the host of an innovative variety program, The Johnny Cash Show, which ran for two years on ABC. His career declined in the 80s, but he was "re discovered" in 1994, when the producer Rick Rubin began recording a series of albums with Cash that drew on his penchant for elegiac and disturbing songs. Cash married June Carter in 1968, and she cowrote one of his biggest hits, "Ring of Fire," which is about their relationship. She was born in Maces, Virginia, in 1929, two years after her mother, Maybelle, and her uncle and aunt, A.P. and Sara Carter, made their first recordings of Appalachian songs for the Victor Talking Machine Company. June and her two sisters performed with their mother as Mother Maybelle and the Carter Sisters, and they appeared regularly with Cash. June Carter Cash died of complications from heart surgery on May 15, 2003, and Johnny Cash died four months later, of complications from diabetes.

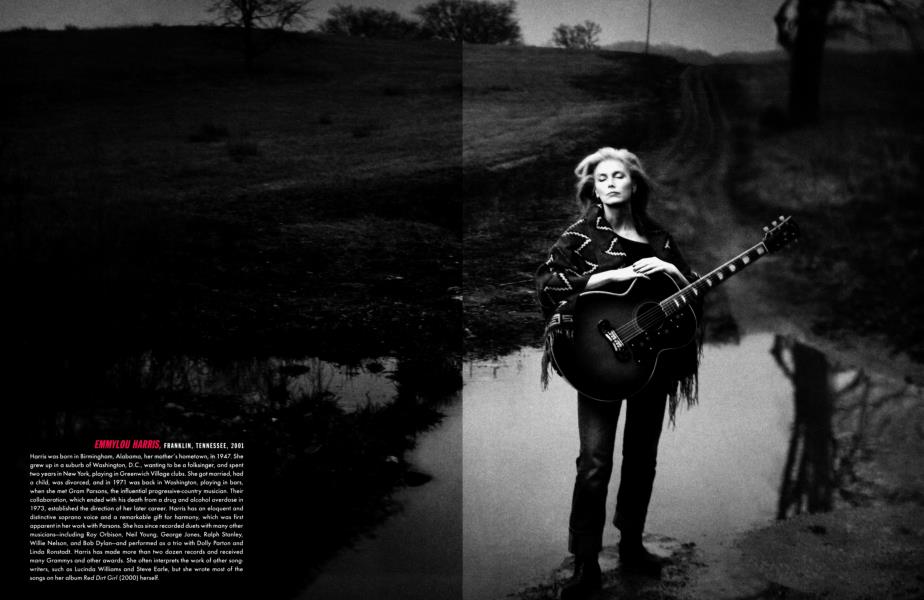

Harris was born in Birmingham, Alabama, her mother's hometown, in 1947. She grew up in a suburb of Washington, D.C., wanting to be a folksinger, and spent two years in New York, playing in Greenwich Village clubs. She got married, had a child, was divorced, and in 1971 was back in Washington, playing in bars, when she met Gram Parsons, the influential progressive-country musician. Their collaboration, which ended with his death from a drug and alcohol overdose in 1973, established the direction of her later career. Harris has an eloquent and distinctive soprano voice and a remarkable gift for harmony, which was first apparent in her work with Parsons. She has since recorded duets with many other musicians—including Roy Orbison, Neil Young, George Jones, Ralph Stanley, Willie Nelson, and Bob Dylan—and performed as a trio with Dolly Parton and Linda Ronstadt. Harris has made more than two dozen records and received many Grammys and other awards. She often interprets the work of other songwriters, such as Lucinda Williams and Steve Earle, but she wrote most of the songs on her album Red Dirt Girl (2000) herself.

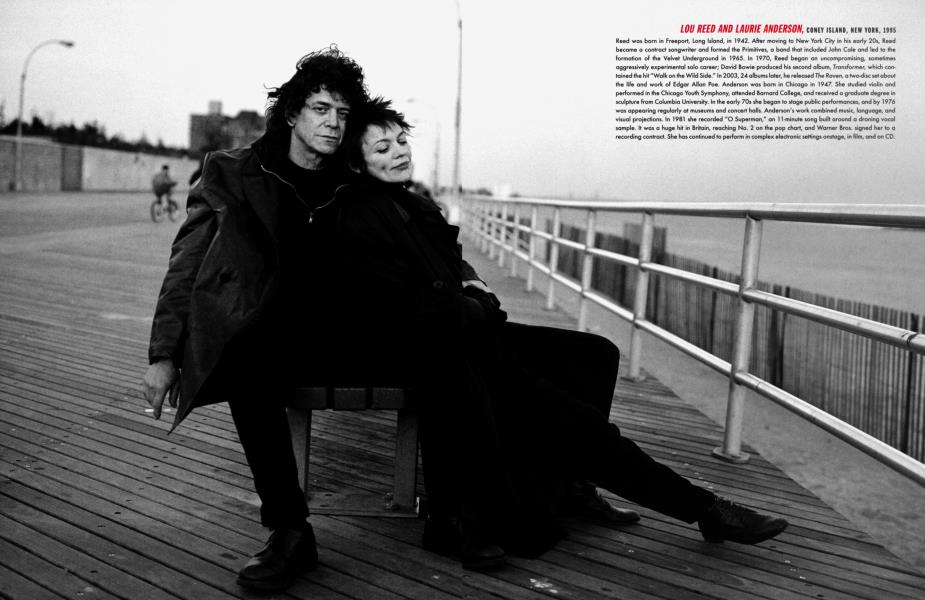

Reed was born in Freeport, Long Island, in 1942. After moving to New York City in his early 20s, Reed became a contract songwriter and formed the Primitives, a band that included John Cole and led to the formation of the Velvet Underground in 1965. In 1970, Reed began an uncompromising, sometimes aggressively experimental solo career; David Bowie produced his second album, Transformer, which contained the hit "Walk on the Wild Side." In 2003,24 albums later, he released The Raven, a two-disc set about the life and work of Edgar Allan Poe. Anderson was born in Chicago in 1947. She studied violin and performed in the Chicago Youth Symphony, attended Barnard College, and received a graduate degree in sculpture from Columbia University. In the early 70s she began to stage public performances, and by 1976 was appearing regularly at museums and concert halls. Anderson's work combined music, language, and visual projections. In 1981 she recorded "O Superman," an 11-minute song built around a droning vocal sample. It was a huge hit in Britain, reaching No. 2 on the pop chart, and Warner Bros, signed her to a recording contract. She has continued to perform in complex electronic settings onstage, in film, and on CD.

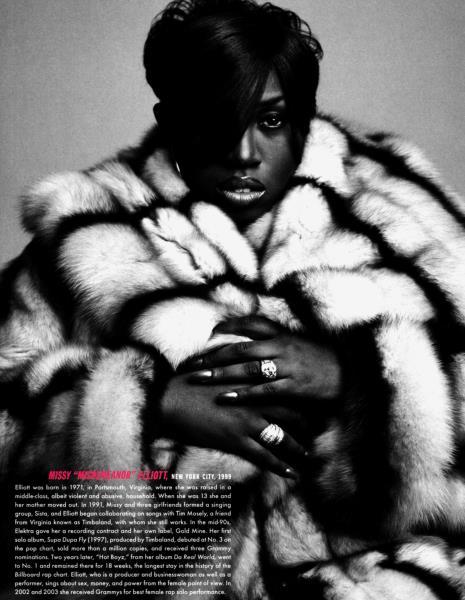

Elliott was born in 1971, in Portsmouth, Virginia, where she was raised in a middle-class, albeit violent and abusive, household. When she was 13 she and her mother moved out. In 1991, Missy and three girlfriends formed a singing group, Sista, and Elliott began collaborating on songs with Tim Mosely, a friend from Virginia known as Timbaland, with whom she still works. In the mid-90s, Elektra gave her a recording contract and her own label, Gold Mine. Her first solo album, Supa Dupa Fly (1997), produced by Timbaland, debuted at No. 3 on the pop chart, sold more than a million copies, and received three Grammy nominations. Two years later, "Hot Boyz," from her album Da Real World, went to No. 1 and remained there for 18 weeks, the longest stay in the history of the Billboard rap chart. Elliott, who is a producer and businesswoman as well as a performer, sings about sex, money, and power from the female point of view. In 2002 and 2003 she received Grammys for best female rap solo performance.

Blige, born in 1971, was raised by a single mother in a housing project in Yonkers, New York. She sang in a church choir and listened to R&B and soul music when she was grow ing up. A karaoke-style tape she mode in shopping mall mode its way into the hands of Andre Harrell, the founder of Uptown Records. He hod the young producer Sean "Puffy" Combs work with Blige on an album that become What's the 411?, which was released in 1992 and sold nearly three million copies. Blige has a raw and warm mezzo-soprano voice that she uses in an R&B style over hip-hop beats, although her later records have a more soulful sound. She is often called the Queen of Hip-Hop Soul. In September her latest album, Love & Life, debuted at , 1.

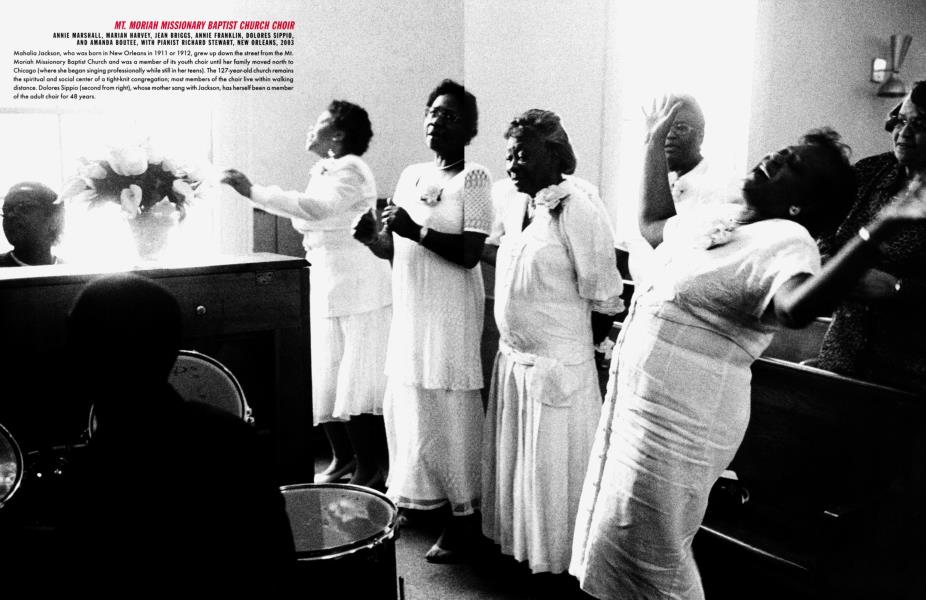

ANNIE MARSHALL, MARIAN HARVEY, JEAN BRIGGS, ANNIE FRANKLIN, DOLORES SIPPIO, AND AMANDA BOUTEE, WITH PIANIST RICHARD STEWART, NEW ORLEANS, 2003

Mahalia Jackson, who was born in New Orleans in 1911 or 1912, grew up down the street from the Mt. Moriah Missionary Baptist Church and was a member of its youth choir until her family moved north to Chicago (where she began singing professionally while still in her teens). The 127-year-old church remains the spiritual and social center of a tight-knit congregation; most members of the choir live within walking distance. Dolores Sippio (second from right), whose mother sang with Jackson, has herself been a member of the adult choir for 48 years.

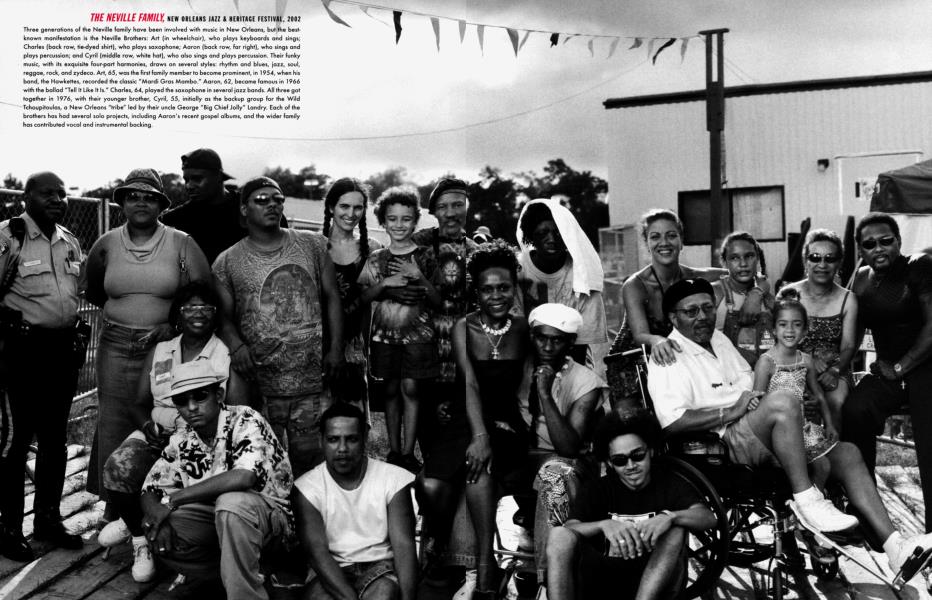

Three generations of the Neville family have been involved with music in New Orleans, but the best-known manifestation is the Neville Brothers: Art (in wheelchair), who plays keyboards and sings; Charles (back row, tie-dyed shirt), who plays saxophone; Aaron (back row, far right), who sings and plays percussion; and Cyril (middle row, white hat), who also sings and plays percussion. Their funky music, with its exquisite four-part harmonies, draws on several styles: rhythm and blues, jazz, soul, reggae, rock, and zydeco. Art, 65, was the first family member to become prominent, in 1954, when his band, the Hawkettes, recorded the classic "Mardi Gras Mambo.* Aaron, 62, became famous in 1966 with the ballad "Tell It Like It Is." Charles, 64, played the saxophone in several jazz bands. All three got together in 1976, with their younger brother, Cyril, 55, initially as the backup group for the Wild Tchoupitoulas, a New Orleans "tribe" led by their uncle George "Big Chief Jolly" Landry. Each of the brothers has had several solo projects, including Aaron's recent gospel albums, and the wider family has contributed vocal and instrumental backing.

The band is a duo. Jack White writes the songs, plays guitar and piano, and sings. Meg White is the drummer and occasionally sings as well. Their music is heavily influenced by the blues, with homages to 60s and 70s rock, and their albums emphasize low-tech production techniques. They claim to be brother and sister, but various rock critics and reporters say there is proof that they were once married. In any case, they were both born circa 1975 and grew up in Detroit, where Jack worked as an upholsterer. They became the White Stripes in 1997, recorded two critically acclaimed albums, and had a hit in 2001 with their third, White Blood Cells. Their second album, De Stijl, was named after the aesthetically austere philosophy of a group of early-20th-century Dutch artists, among them Mondrian, and Jack has said that he and Meg think of the band as an art project, although their success has come less from their conceptual conceits than from the visceral effects of their songs. Their fourth album, Elephant, was released earlier this year.

LED BY THE THEME BRASS BAND AND THE BLACK MEN OF LABOR SOCIAL ORGANIZATION. NEW ORLEANS, 2003

Jazz funerals are unique to New Orleans, where they originated in the 19th century, fusing West African funerary practices, the European custom of brass-band celebrations, and the evolving musical style that would eventually become jazz. The funerals encompass two very different moods. There is a somber march, traditionally to the gravesite, accompanied by hymns or other down-tempo music. The procession returning from the cemetery is joyous, with musical improvisations by the band. Bystanders join the official mourners in a flamboyant display of dancing. The funerals are typically sponsored by a social club or benevolent association, with members distinguished by decorative sashes, hats, and other ornamentation. Placide Adams was a member of a renowned musical family in New Orleans. He joined the family band as a drummer when he was 13, and in later life he was known as a traditional New Orleans jazz bass player. He died on March 29, 2005T at the age of 73, a few weeks before he and his band were to appear at the 34th annual New Orleans Jazz Heritage Festival.

Excerpted from American Music, by Annie Leibovitz, to be published in November by the Random House Publishing Group; © 2003 by Annie Leibovitz.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now