Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

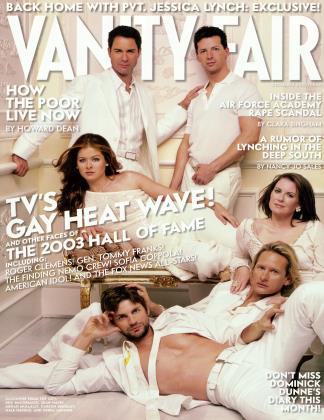

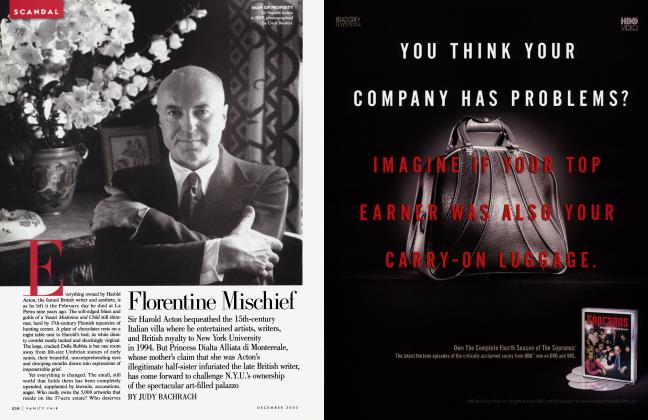

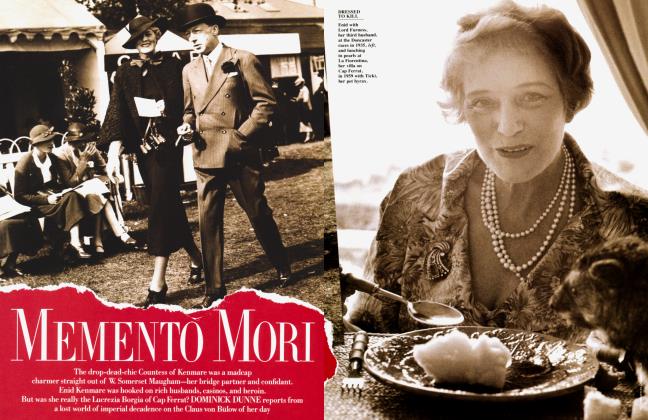

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA link between Kobe Bryant and the Moxley murder, says Robert Kennedy Jr. No link between the Sansum-gallery scandal and Dennis Kozlowski's trial, says the Manhattan D.A. The author investigates both possibilities as one of the most admirable figures in the O.J. saga takes his secrets with him

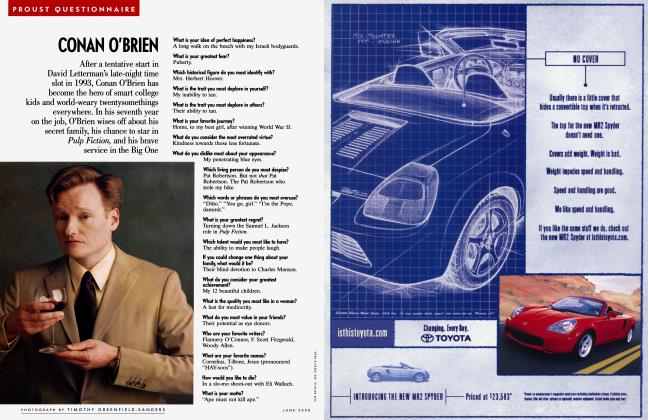

December 2003 Dominick Dunne Timothy Greenfield-SandersA link between Kobe Bryant and the Moxley murder, says Robert Kennedy Jr. No link between the Sansum-gallery scandal and Dennis Kozlowski's trial, says the Manhattan D.A. The author investigates both possibilities as one of the most admirable figures in the O.J. saga takes his secrets with him

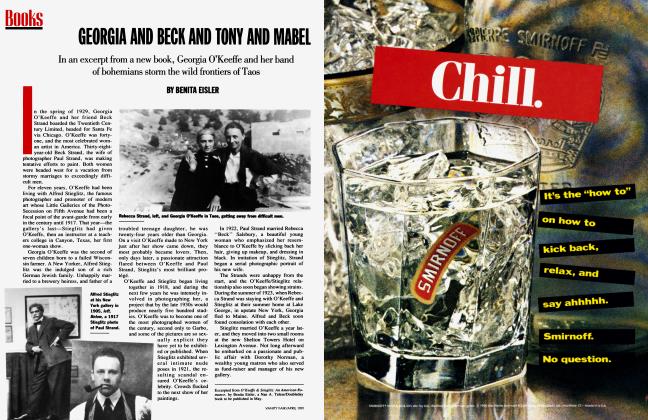

December 2003 Dominick Dunne Timothy Greenfield-SandersAt a September cocktail party that Graydon Carter, the producer Harvey Weinstein, and Jonathan Burnham, president of Miramax Books, gave at the Four Seasons restaurant for 375 of the most notable and powerful people in New York to honor Madeleine Albright on the publication of her memoir, Madam Secretary, Manhattan district attorney Robert Morgenthau, a venerable, 84-year-old gentleman of dazzling importance in the law-and-order department of the city, spoke to me. I had met him once, but we had never conversed, although I am a great admirer of his. Several days later, when the criminal trial of Tyco C.E.O. Dennis Kozlowski began, Christopher Byron would write in the New York Post, "Morgenthau is without question the greatest living prosecutor in America today, with a record in both federal and state law enforcement that spans four decades, seven New York City mayors, and nine U.S. presidents." At the Four Seasons, Morgenthau said simply, "When are you going to write about that case again?" The unwavering stare that accompanied his question was overpowering.

I didn't say, "What case?," although I have reported in this diary on various ongoing cases, including those of Phil Spector, Robert Blake, and Michael Skakel, which I will come to later. I knew exactly what case he was talking about—the one involving James Sansum, the young antiques dealer on the Upper East Side charged with grand larceny and criminal possession of property in the amount of half a million dollars allegedly stolen from his former employer and once close friend, Helen Fioratti, a well-known antiques dealer, whose gallery, L'Antiquaire, has some of the swellest people in the world, including the royal family of Kuwait, for clients. I replied to the district attorney, "I'll be writing about the case again in the issue after next."

We hesitated, each waiting for the other to speak, but neither of us did. While Sansum's involvement in the unpleasant affair is a devastating blow to his life and career, in the annals of crime in New York, this antiques-shop fallout is a relatively minor event to engage a man of Morgenthau's stature. Finally I said, "Would you like me to call you?" "Yes, I would," he replied. Then we moved on to different groups at the cocktail party.

A few days earlier I had attended a hearing on the Sansum-Fioratti case at the courthouse on Centre Street, at which a request for discovery was to be presented and the warrant which had allowed for the search of Sansum's apartment at gunpoint was to be challenged. What some people may not have known was that a civil suit had previously been filed by Sansum against Helen Fioratti for "mishandling gallery finances (including paying him in expenses instead of a salary) and allegedly diverting millions in business income to personal and foreign accounts," as Art & Auction magazine reported. Lawyers for both sides were on hand, but the judge surprised everyone by calling an end to the hearing.

The morning after the Madeleine Albright cocktail party, I called Morgenthau at his office and left my number in Connecticut. He rang me back late that afternoon. We spoke briefly about the party. "It was a little crowded for me," he said. I was hoping to get information about the Sansum case from him, but, great lawyer that he is, he didn't tell me a thing. I found myself doing all the talking.

I told him that I had become interested in the case, which is not the sort I usually write about, after some important people in town let me know that they felt Sansum was being shafted. I discussed the list of allegedly stolen objects and pictures and said that I didn't understand why, according to Sansum's lawyer, Michael Lumer, the assistant district attorney, Robin McCabe, had not shown much interest in the fact that certain of the items Fioratti claimed had been stolen were still in her shop or had been spotted in her booth at an antiques fair. In the case of one missing object, according to Sansum, she had collected insurance after it was stolen by a moving man. (McCabe declined to comment.) I pointed out that the list also included six pictures painted by Fioratti's daughter, Arianna, who had briefly been James Sansum's lover when they were at Harvard together and later was one of his closest friends. For Helen Fioratti to list her daughter's amateur pictures as stolen property in a lawsuit that could send Sansum to prison for 15 years seemed to me egregious. I was extremely dismissive of Arianna's paintings, photographs of which I had seen. "Valueless," I think I called them. I also talked about the practice in the antiques business of paying commissions to employees on big sales with an object or a drawing instead of cash. In such transactions, papers are rarely drawn up. To me, I told the district attorney, the list of stolen objects, which had led to the search of Sansum's apartment, was suspect. Then I went a step too far. I said, "There is a rumor going around that your office has made a deal with Helen Fioratti for her help in the Dennis Kozlowski case." Morgenthau's tone, which had been pleasant, turned icy. "My office has no deal with Mrs. Fioratti concerning Kozlowski," he said. According to Sansum, certain antiques in Kozlowski's Park Avenue apartment had been purchased at L'Antiquaire, but no sales tax had been paid, because the antiques had allegedly been sent to his decorator on Nantucket. As of this writing, the Kozlowski case is in a New York courtroom, and the unpaid sales tax could become an issue in the future. Fioratti's lawyer, Michael C. Miller, however, assures me that she is not scheduled to be a witness. The Fioratti-Sansum case is set to go to trial November 14.

"My office has no deal with Fioratti concerning Kozlowski."

I had a letter from a man I know in New York telling me that Helen Fioratti, who is a close friend of his, was back in New York from Italy and would like to see me. I called her at her shop and said I'd like to talk to her about her lawsuit against Sansum. She said she would talk to her lawyer and get back to me. Miller later phoned to say that she didn't want to meet with me, but that she would send me a list of people to call about her.

I spoke with three of those people, all of whom were familiar with her business and one of whom was an art dealer. They had nothing but praise for Fioratti's hard work, which included a great deal of traveling. In Sansum, they said, she thought she had found the ideal person to relieve her of the day-to-day operations. "She put all her faith in James," the art dealer told me. "She didn't want him to use her as a stepping-stone. That's why she gave him ownership. When he decided to change lifestyles, he became unfriendly with her." Another friend of Fioratti's, a man who is an art expert, said, "I never liked James. He spoke to her very abruptly. I think you're wrong to portray Helen as a homophobe."

The more people I talk to on both sides of this intriguing case, the more I feel that in the end it will not come to trial. It is like a divorce that has turned ugly.

My last news from Monte Carlo was that Ted Maher, the male nurse found guilty of setting the fire that caused the death of the billionaire Edmond Safra and his nurse Vivian Torrente, had escaped from the Monte Carlo prison in a dramatic feat of derring-do, only to be caught hours later in Nice and sent to a much tougher prison in France. I recently heard from Donald Manasse, Maher's lawyer in Monaco, that Maher is to be extradited back to Monaco, where there will be a trial for the escape, which should begin early next year. The maximum sentence is one year of additional imprisonment. Once Maher is tried in Monaco, he will be sent back to France. Maher is certain to face some hostility in the Monaco prison, where he once reigned as its most important inmate. As a result of his escape, the head of the prison, Charles Marsan, who was both popular and humane, was suspended and then took early retirement. He is said to be greatly missed at the prison.

During the earlier trial in Monte Carlo, the chief of police, Maurice Albertin, would accept no criticism of his officers' performance on the night of the fire, which was generally felt to be appalling. At one point early on, Lily Safra had blamed the police for the death of her husband, but she rescinded her accusation during the trial. Donald Manasse told me that the police chief has also taken early retirement. In an interview with a local magazine before he left office, he admitted that a number of policemen had been disciplined for mistakes they made during the botched rescue attempt. He said he had not revealed this at the trial because he did not want to influence the outcome.

On the spur of the moment last summer, I flew to England to say good-bye to one of my best friends, who was dying but putting up a brave fight to survive. When I first knew him, in 1963, his name was Henry Herbert. A young Englishman who wanted to be a film director, he came to my house in Beverly Hills for a visit. A cousin of his was a friend of my wife's, and we planned a party to welcome him, with a guest list that included a lot of movie people he was eager to meet. However, President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas that morning, so we canceled the party and spent the next five days sitting in front of a television set, watching that extraordinary moment in American history. I hate the word "bonding," but it was the ultimate bonding experience. In 1993, on the 30th anniversary of President Kennedy's assassination, Henry sent me a fax at the Chateau Marmont, in Hollywood, where I was staying while I covered the Menendez brothers' trial. He ended by saying, "Do you realize we have been friends for 30 years?"

He made several films in England, including a racy one which caused quite a sensation because it starred Koo Stark, who had had an affair with Prince Andrew. Then his father died unexpectedly at a young age, and my friend's life changed. Henry Herbert, the film director, became the 17th Earl of Pembroke and inherited Wilton House, one of the great houses of England, with a vast estate to run and oversee. Stanley Kubrick used the house in the film Barry Lyndon, the director's glorious evocation of 18th-century aristocratic life in England.

No one ever mentioned the presence of two unfamiliar boys.

Henry married twice. He had three daughters and a son from his first marriage, and three more daughters from his second. Then he became ill. As the disease worsened, his determination to "beat it" was inspirational to me. He turned more and more to homeopathic cures and healers and traveled abroad to a number of clinics, including one on Staten Island, in New York. Along the way he discovered a strong spiritual self.

Some of the rooms of his great house, including the famous double-cube room, are open to the public. Henry had given me the code to get in a side door that the family uses. Unlike in the old days, there was no butler in sight, or any maids. I knew where to go. Henry was in the library, a vast room the width of the house, which has old masters on the walls and looks out on the private family garden, the orangery, and the swimming pool. He was still remarkably handsome, although his looks had been ravaged by his illness. What struck me was how alone he seemed to be in his 100-room house. It was unbearably sad.

As many times as I had visited the house, I never knew there was a chapel in it. It was closed for years, but Henry had reopened it. "I meditate there for two hours each day," he said. It was where he met with his healer several afternoons a week. Although he was in obvious pain, there was a serenity about him I had never seen before. He talked about his belief in God. On the estate was a small 18th-century house that various bachelor uncles and family friends have lived in over the years. It was empty now, and he planned to turn it into a healing center for people with cancer. "I must make plans or it's over," he said, referring to his life.

He was tired. It was time to say good-bye. "This is all William's now," he said, referring to his son, as he slowly rose from his chair. When we shook hands, we both knew it was for the last time.

In October his wife Miranda called to tell me that Henry had died. Both of his wives and all of his children were with him. I'm so glad I went to see him.

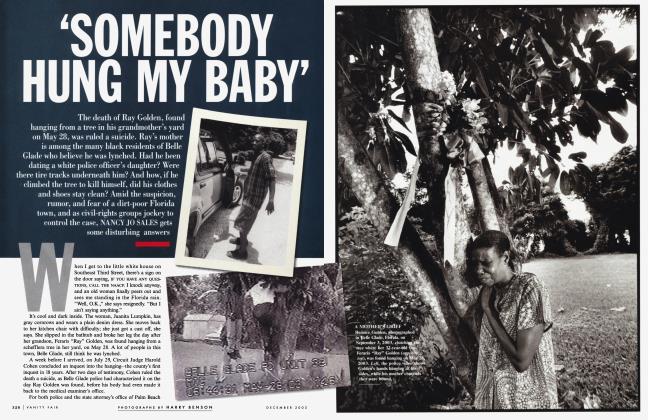

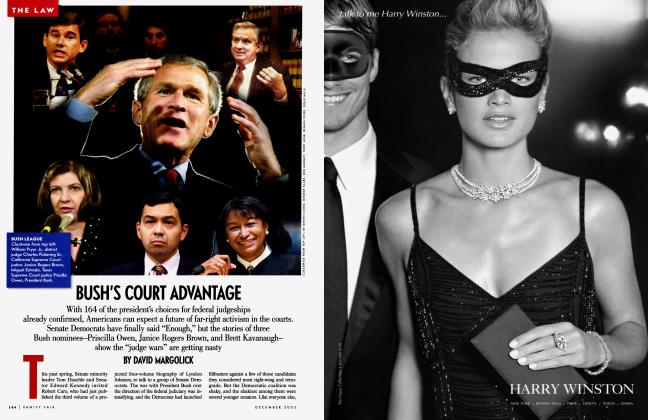

I find it hard to believe the latest scenario in the case of Michael Skakel, who was found guilty last year and sentenced to 20 years for the murder of Martha Moxley in Greenwich, Connecticut, in 1975. Now, nearly 30 years after the crime was committed, a new voice has emerged with another version of Martha Moxley's murder. According to Gitano "Tony" Bryant, a former classmate of Michael Skakel's at Brunswick, a private school for boys in Greenwich, the murder was committed by two friends of his from the Bronx who happened that night to be in Belle Haven, the ritzy gated enclave where the Skakels and Moxleys lived. He said that the two friends had talked about getting a girl "caveman-style," clubbing her and dragging her to a remote area for sexual pursuits. One of these friends was African-American. Bryant let it be known that he was a cousin of Kobe Bryant, the Los Angeles Lakers guard who has been charged with raping a young woman in Eagle County, Colorado. What Kobe Bryant doesn't need at this moment in his troubled life is having his name mentioned in connection with a famous murder case with which he had no involvement whatsoever. Later, Gitano Bryant distanced himself from his relationship with Kobe Bryant, and the unsubstantiated but often repeated rumor is that Kobe's infuriated lawyers had gotten to him. Bryant, who lives in Miami and lost his tobacco company last year in a legal settlement, has a felony rap against him and is therefore not a totally credible witness. He did not contact the police himself. Two years ago he told the story to two other former Brunswick students with whom he kept in touch. One of them, Crawford Mills, went to the authorities and spoke to both the prosecutor, Jonathan Benedict, and Skakel's defense lawyer Mickey Sherman. Both sides dismissed the story as improbable.

The night of the murder was the night before Halloween, known to the young people in Greenwich as mischief night. In almost 30 years no one has ever mentioned the unlikely presence that night of two unfamiliar boys, aged 15 and 17, in their midst. In the aftermath of the murder, all sorts of wild stories were put forth, including a theory that a vagrant who had wandered in from Route I-95 might have committed the crime, but no story ever surfaced about two boys from the Bronx. Without meaning to be politically incorrect, I think it's safe to say that any parent looking out the window that night and seeing two strangers, one of them black, in the guarded community would have immediately called the police. Bryant claimed the boys had spent the night at the home of Geoffrey Byrne, a close friend of Martha Moxley's. Byrne was 11 years old at the time. The idea that the two youths would have spent the night in Belle Haven after committing a murder there seems highly unlikely. It is also highly unlikely that two teenagers from the Bronx would be close enough to an 11-year-old in Belle Haven to be his overnight guests. At the time of the homicide, Geoffrey Byrne said nothing about Bryant or his friends. Byrne died six years later of an overdose.

Robert Kennedy Jr. latched onto Bryant's story. Defense investigators were sent to make a 90-minute video of Bryant telling it. Kennedy then made the inevitable appearance on television, this time to talk to Lesley Stahl again on 48 Hours. Only last February, in a 14,000-word article in The Atlantic Monthly about the Skakel case, Kennedy pointed the finger of guilt at Ken Littleton, the live-in tutor, whose first night on the job happened to be the night of the murder.

In the meantime, both men mentioned by Bryant have been located, and both have denied any involvement. It is most unlikely that the verdict would be overturned on appeal based on what amounts to double hearsay. Perhaps this is part of an attempt to undermine Mickey Sherman—whom the Skakels paid $1.7 million—for not having investigated the story and to make the case for an appeal. The new lawyers for Skakel have requested that Detective Frank Garr, who has been on the case for 27 years, be removed from it.

"It was the blood. OJ. could never explain about the blood."

On October 4, I attended the wedding of my son Griffin to a beautiful young lady named Kelly Monk at his house in Rhinebeck, New York. It rained cats and dogs, but the wedding was still held outdoors as planned, with everyone holding umbrellas before racing to a tent for the reception. My granddaughter, Hannah, who is 13, was a bridesmaid, and 5-year-old Maya Hawke, daughter of Uma Thurman and Ethan Hawke, was the flower girl. It was wonderful.

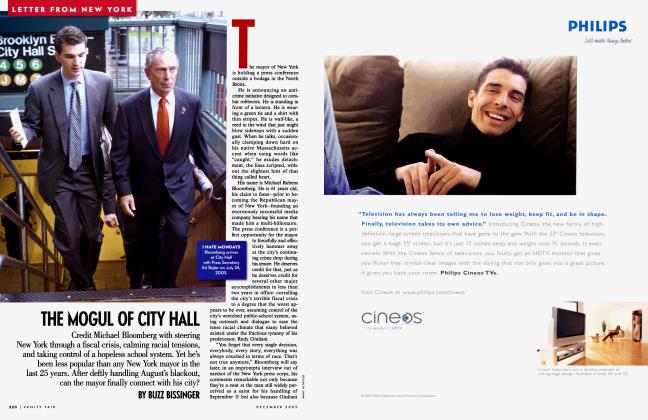

It is impossible to explain to anyone who wasn't there how full of hate the courtroom was during the last weeks of the O. J. Simpson trial in Los Angeles in 1995. There were extra police in the corridors, just in case, and the crowd outside the courthouse was positively scary as people screamed their approval of some participants in the proceedings and demonstrated their loathing of others, all of whom had become familiar public figures during the yearlong trial. One man, however, a pivotal player in the days following the murder, somehow transcended the anger and abuse. His name, Robert Kardashian, is relatively unknown. A successful lawyer and businessman as well as a member of a prominent Armenian family in Los Angeles, he was one of Simpson's closest friends, and as a silent member of Simpson's Dream Team he stood by O.J.'s side throughout the ordeal of the arrest and the highly publicized trial. Their friendship dated back to O.J.'s undergraduate days at the University of Southern California, where he was the legendary star of the football team.

Kardashian rushed to Simpson's home as soon as he heard the news of the murder on television. He could not and would not believe that his great friend was responsible for the heinous slashings of Nicole Simpson and Ronald Goldman. Against the warnings of his friends that his business would suffer as a result and that people would drop him, he believed in the innocence of Simpson. To avoid the onslaught of media at his house on Rockingham Drive in Brentwood, Simpson and his girlfriend Paula Barbieri were secreted in Kardashian's house in Encino. It was from there that Simpson took off with his pal Al Cowlings in the white Bronco, leading to the infamous freeway chase which was watched on television by 90 million people. It was Kardashian, standing beside Robert Shapiro, Simpson's lawyer, who read what was thought to be Simpson's suicide note. It was Kardashian who was photographed carrying away Simpson's Louis Vuitton garment bag after Simpson returned to the house on Rockingham following the chase. During the trial, Kardashian visited his old buddy nightly in the Los Angeles County jail. But then, as the months went by, Kardashian reluctantly ceased to believe in Simpson's innocence. After the trial was over, he said to me one day, "It was the blood. He could never explain to me about the blood, how his blood was there."

The video of Simpson, Johnnie Cochran, and Kardashian at the moment of Simpson's acquittal, which was shown over and over, is fascinating to watch today. Simpson is smiling. Cochran is ecstatic. Kardashian is troubled. Had Simpson been sent to prison, I think Kardashian would have been a faithful visitor. As it was, he went briefly to the champagne celebration at Simpson's house on Rockingham, but the friendship was over. Kardashian subsequently collaborated with Lawrence Schiller on his excellent book, American Tragedy: The Uncensored Story of the Simpson Defense. I always liked Kardashian, even when the division of opinion in the case was most bitter. I would see him when he came to New York, and I had lunch with him in Los Angeles when I was there. He once asked me if I could introduce him to Salma Hayek, but I didn't know her.

During the trial, Kardashian was engaged to a beautiful young widow named Denice Halicki, whose husband had been killed on a movie set in a stunt scene that went wrong. She was blonde, glamorous, and drove a Rolls-Royce to court every day. His first wife, Kris, the mother of his four children, is married to the Olympic gold medalist Bruce Jenner. Kardashian and Halicki never married, but they stayed friends. As predicted, his life was difficult after the trial. His loyalty had cost him friendships and hurt his business.

In September, Denice Halicki called me to say that Robert was dying. He had married again two months earlier, had gotten ill in Italy on his honeymoon, and had been diagnosed with cancer. I called and spoke to him the day before he died. I told him I admired him for standing by a friend but also for having the guts to realize he had been wrong. He told me he was grateful for my call. Did Robert Kardashian take a secret or two to the grave with him? Probably.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now