Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEDITOR S LETTER

Rob the Vote!

It's about time Americans stopped worrying about the Baathists, Shiites, and Islamists playing footsie with free elections in Iraq, and paid attention to more pressing electoral problems we have here at home. The 2000 presidential election told us that even in a nationwide election in a country of 292 million people, important victories can be won by astonishingly slim margins. In Florida, remember, Bush beat Gore by just 537 votes.

Matters of trust in the system facing American voters appear to be even worse than they were in 2000. Indeed, the 2004 presidential election has the potential to be catastrophic. Even after the debacle in Florida in 2000, voting rolls are still notoriously slapdash affairs. The U.S. government gives local election officials general instructions on how to maintain the rolls and then pretty much leaves the locals to their own devices. As The New York Times said in an editorial: "The lists of eligible voters kept by localities around the country are the gateway to democracy, and they are also a national scandal."

In his book The Best Democracy Money Can Buy, Greg Palast tallied the number of felons and so-called felons who were refused the right to vote by Katherine Harris, Florida's top election official, and her predecessor; his count came to an estimated 97,700. State law prohibits felons from voting in presidential elections, and most of those purged from the rolls were African-Americans and, by extension, Democrats. Eight thousand of the people Harris initially delisted reportedly hadn't even committed a felony. Wallace McDonald, for instance, was dropped from the rolls because of a misdemeanor he received for falling asleep on a bus-stop bench in 1959. To be fair, Harris might just have been stretched too thin. In addition to her work as the state's Chief Election Officer, she was also co-chair of the Florida Bush campaign.

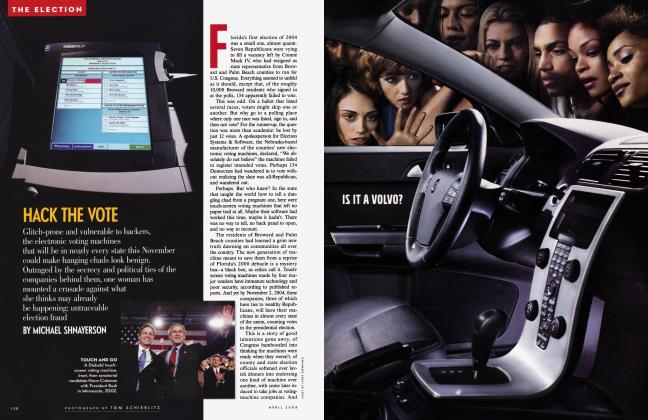

There is the even more serious matter of voting machines themselves. Many polling districts in the country now rely on electronic voting machines. Some of these use optical scanners to read paper ballots, but the majority, known as Direct Recording Electronic voting systems, or D.R.E.'s, have touch-screen technology similar to those in A.T.M.'s. Unlike A.T.M.'s, though, most D.R.E.'s don't spit out a printed record of a vote, leaving no paper trail should a recount be required. Furthermore, according to critics, they are troublingly susceptible to outside manipulation.

In some of Florida's voting districts, including Volusia County, where A1 Gore initially registered an impossible minus 16,022 votes in 2000, the machines used were optical scanners. Those negative votes played a part in the domino effect that resulted in the Bush victory. On election night, the Volusia votes, together with disputed returns from other counties, showed Bush with a significant winning margin. John Ellis, a political analyst for Fox News, declared him the winner at 2:16 on the morning after election day. The other networks reported the same news soon thereafter, and Gore prematurely called his opponent and conceded the race. Ellis, by the way, is George W. Bush's cousin.

(Not to cast aspersions on the accuracy of Florida's electronic voting machines, but James Harris, the Socialist Workers Party presidential candidate, received almost 10,000 votes in Volusia County in 2000, which was nearly half the number of votes he got nationwide.)

Voting machines, perhaps the single most important electronic devices in American democracy, are outsourced to private concerns. The manufacturers are permitted to operate in virtual secrecy, their technology is kept secret, and they have little in the way of federal oversight. D.R.E.'s are now part of a $3.9 billion business, and divided for the most part among four companies, three of which have staunchly Republican ties. As Michael Shnayerson points out in his report on the voting-machine scandal we face as we go into the next election ("Hack the Vote," page 158), we wouldn't know much about any of these companies were it not for Bev Harris, a 52-year-old grandmother and occasional journalist, who has become the point person on the D.R.E. mess. After the 2002 elections, she noticed discrepancies between advance polls, which showed Democratic candidates ahead, and final results, which had some Republicans winning with suspiciously wide margins. Since then she's uncovered all manner of conflicts of interest between voting-machine people and the Republican Party. (She originally posted her findings on the Internet. Her book on the subject, Black Box Voting: Ballot-tampering in the 21st Century, has just been published.)

Walden O'Dell is chairman and C.E.O. of Diebold, one of the largest electronic-voting-machine manufacturers in the country. He also happens to be a Bush "pioneer," which means he's raised at least $100,000 for the president's re-election campaign. In mid-2003, he helped organize a fund-raiser attended by Vice President Dick Cheney that brought in a further $600,000. A few months later, O'Dell called upon Ohio Republicans for even more money for the party, proclaiming his commitment to help "Ohio deliver its electoral votes to the president next year." Diebold itself has given almost $100,000 in soft-money contributions to the Republican National Committee. (The company has donated nothing to the Democrats.) One of the company's directors raised $200,000 for the Bush re-election campaign, and 11 other Diebold executives anted up $2000 apiece.

Georgia gave its contract for D.R.E.'s to Diebold. They were supposed to be hackproof. Bev Harris came to believe that not only were they not hackproof, but that all 22,000 machines had the same entry password: "1111." State officials had them tested by two independent labs, which gave them the thumbs-up. But how independent were the labs? One of them had given $25,000 to the Republican National Committee in 2000.

Maryland election officials hired computer experts to test the security of that state's Diebold machines. The experts easily hacked into the D.R.E.'s, either directly or through telephone lines. The machines failed the test completely. Diebold's initial response wasn't to address the problems, but to issue a press release entitled "Maryland Security Study Validates Diebold Election Systems Equipment for March Primary."

In 2002, Diebold had bought G.E.S., a Texas-based company that specialized in voting machines. One of its directors had been accused of tax fraud and money laundering in Canada, and faced stock-fraud charges in the U.S. He's gone. But a man named Jeffrey Dean was subsequently hired by G.E.S. Dean's qualifications: he'd served time on 23 felony counts of embezzlement involving, as court documents pointed out, "a high degree of sophistication and planning in the use and alteration of records in the computerized accounting system that defendant maintained for the victim" in a law firm. Another employee of G.E.S., and now Diebold, was John Elder, a longtime colleague of Dean's, who was brought in to oversee the printing of paper ballots and punch cards for use in some states. Elder had served nearly five years in prison for cocaine trafficking.

The situation is such that having the United Nations monitor the presidential election is not all that far-fetched an idea. We could alternately bring in former president Jimmy Carter's organization. But it only oversees elections in developing countries. So for now we're stuck with the sort of people in charge of the voting machines and the sort of machines that will be registering your vote on November 2. Have a nice day.

GRAYDON CARTER

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now