Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

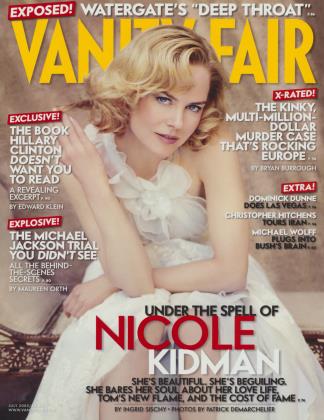

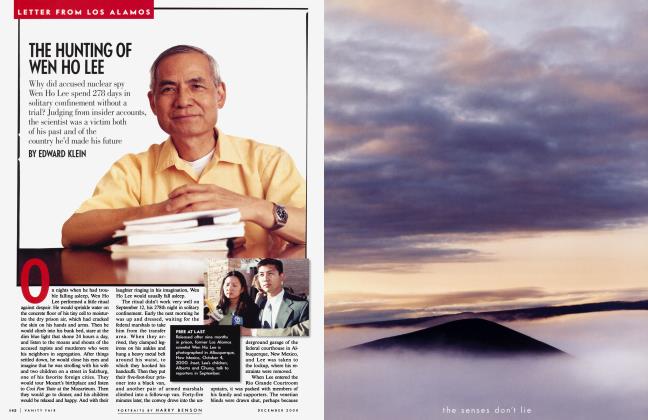

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAs Hillary Clinton seeks re-election to the U.S. Senate next year, she is also considered a Democratic front-runner for the presidency in 2008. But back in 1999, when the First Lady began to contemplate a political career of her own, she faced serious obstacles, not least the disdain and distrust of the powerful man she hoped to replace, New York senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and his tough-minded wife, Liz. In an excerpt from his new book, EDWARD KLEIN takes an inside look at Clinton's first campaign: the muscle, the money, and the lingering scent of scandal

July 2005 Edward KleinAs Hillary Clinton seeks re-election to the U.S. Senate next year, she is also considered a Democratic front-runner for the presidency in 2008. But back in 1999, when the First Lady began to contemplate a political career of her own, she faced serious obstacles, not least the disdain and distrust of the powerful man she hoped to replace, New York senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and his tough-minded wife, Liz. In an excerpt from his new book, EDWARD KLEIN takes an inside look at Clinton's first campaign: the muscle, the money, and the lingering scent of scandal

July 2005 Edward Klein'In the winter of 1999, I was at Camp David with some other major Democratic donors who were close to Hillary, and there was talk of her running for Pat Moynihan's Senate seat," said a prominent Democratic fund-raiser. "At one point Hillary joined us, and the talk started to drift to the subject of her throwing her hat in the ring. We all started to engage her, but she didn't want to be engaged.

"And she explained why," this Friend of Hillary continued.

"'I've had some pretty tough few years in the White House,' she told us, referring to the impeachment battle. She added, 'And now I want to do what I want to do.'

"I figured she had decided not to run. But a couple of months after that conversation at Camp David, it became clear in a number of ways that she wanted financial support. Hillary operates in a different mode than most politicians when it comes to money. Most politicians have to make pilgrimages to people like me, and ask me to help them raise money. Hillary doesn't have to do that. She has star power. A lot of rich people are always dying to be near her and give her money."

By late February, Hillarymania was in the air. Both Newsweek and Time put her on their covers. In early March she invited a group of New York State's top Democratic elected officials and operatives to the White House in order to find out how they felt about her getting into the race.

All the people around Hillary wanted to see her step out from her husband's shadow and run for office. It was high time she stopped focusing on his political survival, they advised her, and started focusing on her own political future.

That spring Hillary gathered yet another group of friends and supporters, this time in the Manhattan office of Alan Patricof, a wealthy venture capitalist who backed Democratic candidates. The subject was money. If Hillary ran for the Senate, the task of raising the money to fund her campaign would fall to the people in the room. Naturally, they wanted some reassurance that Hillary—whose approval rating was now an astonishing 78 percent in New York City and 65 percent statewide—had thought through the personal implications of running for public office.

"How are you going to handle Monica Lewinsky?" asked one of the women at the meeting.

"I decided that, because of Kosovo, for the good of the country I needed to stand by the president of the United States, the commander in chief, during perilous times," Hillary said, reciting an answer that pleased some of her supporters but sounded less than convincing to others. "And we needed to show that the office of the president was strong and intact. And I had to show that what had gone on was between Bill and me."

No matter what she said in public about being undecided, Hillary was now privately committed to running. However, she did not want to look like an arrogant interloper, especially in the eyes of New York State's influential Democratic county leaders.

There were 62 counties in New York State, and 62 county leaders to woo. Ten of those counties had significant voting populations, and Hillary's first order of business was to get the support of the leaders in those counties. These men and women had devoted their lives to the Democratic Party, and they were not eager to welcome a Joannie-come-lately like Hillary. Without their support, however, Hillary had no chance of winning the Senate nomination.

"Before she announced the embryonic stage, her campaign staff did a helluva job with the county leaders," said a Democratic Party activist who was intimately familiar with the state's politics. "Judith Hope, who was then the state Democratic Party chairman, went around the state and told the county leaders, 'Listen, you may not like this idea initially, but do me a favor and don't say anything yet.'"

Hillary needed to convince the county chairmen that she could beat her likely Republican opponent, New York City's mayor, Rudolph Giuliani, on his home turf and hold her own in the Republican suburbs as well as in conservative upstate New York.

That was a big order, and Hillary turned for help to image-maker Mandy Grunwald, a formidable figure both politically and physically. Mandy stood nearly six feet tall and had a booming voice and a thick head of black hair. A bundle of nervous energy, she had been known to chain-smoke Marlboros. Some of her Republican counterparts in the political-consulting business joked that she looked like the Marlboro man in drag.

Though she had grown up in a Republican environment (her father, the late Henry Anatole Grunwald, had been the editor in chief of Time Inc.), Mandy was a New York liberal to her core. After working on Bill Clinton's first presidential campaign, she was hired by the Democratic National Committee. But in the wake of the health-care fiasco and the Republican takeover of Congress in 1994, she was sidelined. Her liberal voice in the White House was replaced by the centrist voice of Dick Morris.

Mandy had been the Harvard roommate of Pat and Liz Moynihan's daughter Maura, and she had made television commercials for three of Moynihan's four campaigns. She had a New York state of mind, and she urged Hillary (who had never lived in New York) to embark on a "listening tour"—traveling all over the state, talking to average New Yorkers about their problems. It was a sophisticated concept, because it deflected the most potent charge against Hillary—that she was a presumptuous outsider who knew all the answers and thought the people of New York owed her a seat in the Senate.

Mandy set up small, intimate meetings, where Hillary—in Oprah-like fashion—could sit on a stage with the president of the local hospital, say, or a union leader, and talk about access to health care and the economy of western New York State. These meetings would give people the opportunity to see that Hillary did not have horns. Many New Yorkers had read that she was cold, mean, and tough. But when they saw her in person, Mandy felt confident, they would find someone who smiled, was funny, possessed boundless energy, and had knowledge of the issues they cared about.

But there was a hitch. Before Hillary could embark on her listening tour, she had to get the blessing of the state's big kahuna: Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan. And everyone knew that Pat and Hillary did not get along.

For years Pat Moynihan had been suffering from back pain, and in the spring of 1999, when he was 72, he had surgery to treat his spinal stenosis. The operation was a success, but his recovery was slow, and by May he still did not feel well enough to make an appearance on the floor of the Senate. However, when Hillary Clinton called to say she would like to drop by for a visit, the gallant senator put on a suit and tie and greeted the First Lady when she arrived.

Pat and Liz Moynihan lived on Pennsylvania Avenue in a modem condominium apartment. They also had a hotel suite in New York City and a 900-acre farm in upstate New York, where the senator had written his 18 books and many of his thoughtful speeches analyzing the ills of American society. Though Moynihan was often portrayed as an intellectual who was above the political fray—he had served both Republican and Democratic presidents before becoming a senator—he was also a shrewd Irish politician who understood power and its uses.

To break the ice with the Moynihans, Hillary began by chatting about the Dalai Lama, whom Pat and Liz had met when Pat was America's ambassador to India. The Moynihans sat and waited for her to come to the point.

According to Moynihan biographer Godfrey Hodgson, from the start the senator's wife did not hide her impression "that Hillary Clinton 'didn't get it,' meaning that she didn't understand how either the Senate or the Senator worked."

As newly appointed chairman of the powerful Senate Finance Committee, Moynihan had urged

Bill Clinton, after his election in 1992, to tackle the issue of welfare reform, which had many supporters in Congress, before he took on the thorny problem of health care. That way, Moynihan had argued, the new president would create a positive legislative record and develop the momentum necessary to push through health-care reform.

The president's decision to ignore this sage advice cost him dearly. In Moynihan's view, the reason for the president's blunder could be summed up in a single word: Hillary. He believed that she had persuaded her husband to go for health care first, and, as everyone knew, she had been put in charge of the effort. Moynihan believed that Hillary's chief motivation was self-aggrandizement; she was determined to seize the favorable attention of the nation in order to enhance her prospects of succeeding her husband in the White House.

Moynihan had publicly referred to Hillary's health-care plan as a "fantasy." And he made no secret of the fact that he found both Clintons difficult to deal with. In his eyes, it was unforgivable that they and their staffs had displayed a complete lack of decorum and had ignored him. Nor did he forgive the Clintons for failing to support his proposals to reform Social Security. He told friends that he had a long list of people he disliked in the Clinton administration, and that at the top of the list was Hillary Rodham Clinton.

"The reason you're not doing well in New York," said Liz Moynihan, "is because Jews don't like you."

In their dealings, he had caught Hillary shading the truth, according to a person close to the Moynihans. For instance, she told people that Moynihan never held hearings on her healthcare plan, when in fact he had held numerous meetings.

Liz Moynihan shared her husband's assessment of Hillary as a liar and dissembler. She and Hillary spent a lot of time together while Hillary was trying to decide whether to run for Pat's Senate seat. Liz told friends that she found Hillary to be one of the strangest people she had ever met. Liz had her own view about what made Hillary that way. "I believe that she believes that God approves of her, and that therefore she can't do anything wrong," Liz told a friend. "I suppose it's a midwestern Methodist view, the equivalent of Nixon and Quakerism."

The Moynihans were deeply disappointed in Bill Clinton. They had expected great things from him and felt that he had squandered a historic opportunity to make a difference. In their opinion, no one in America was better able than Clinton to speak directly to both blacks and whites on the issue of race. Yet, for all his special gifts, Clinton had let the opportunity pass.

What's more, the Moynihans thought that Bill Clinton should have resigned the moment the Monica Lewinsky scandal became public, rather than put the country through the trauma of an impeachment process. And they found Hillary's defense of her husband during the Lewinsky scandal to be nothing short of incomprehensible.

When Hillary had finished discussing the Dalai Lama with the Moynihans, she turned to the real reason for her visit. She had been doing some polling in New York, she said, and she was sorely disappointed with the lackluster response by the voters in New York City to her candidacy.

Liz Moynihan, who had managed all of her husband's Senate campaigns, did not put much store in polls. In fact, she generally commissioned a poll only once every six years, during the middle of each of Pat's terms, and three additional ones during an election campaign. The results of the polls were never used to influence how the senator voted, or what he said on any given issue. The results were used purely to make commercials to reach voters who, according to the polls, did not know their senator well.

Hillary, according to one insider, found it hard to believe that the Moynihans did not poll as frequently as she and Bill Clinton did—which was as often as twice a week.

"So," Liz Moynihan said, "you're interested in the secret of my success."

"Yes," Hillary said.

"I have a good candidate," Liz said. "People like him and trust him."

"Well ..." Hillary began.

"The reason you're not doing well in New York," said the straight-talking Liz, "is because Jews don't like you."

Hillary was taken aback. No one talked to the First Lady like that.

"Is it because of what they say I said about the Palestinians?," Hillary said. A year earlier she had advocated a Palestinian state.

"The thing that is wrong with that statement isn't what 'they say' you said," Liz said sternly. "It's that you said it. And then there's health care."

"Health care?," Hillary said.

"'Yes," Liz continued, "health care. New York has a lot of teaching hospitals, and you want to close them down. New rk has lots of Jewish doctors, and those doctors have lots and lots of wives and relatives and patients, and they don't like what you want to do."

"I'm interested in what you say about health care," Hillary said, "because I had a bill that would protect the teaching hospitals—"

"Hillary!," Liz interrupted. "That's Pat's bill."

"Oh," said Hillary, "did he have one, too?"

Hillary wasn't an elected official, and yet, according to the insider, she was talking as though she had introduced her own bill. And she was looking right at Liz Moynihan and comparing herself to Pat Moynihan, who had one of the most distinguished records in the history of the U.S. Senate.

At that point, Pat Moynihan had had enough. "You have to excuse me," he said to Hillary, getting up slowly from his chair, favoring his back. "I told them I would go to the Senate today."

He left the room. But he did not go to the Senate. He went to an adjoining room and waited for Hillary to leave.

Liz thought that Hillary would leave as soon as Pat did. But the First Lady stayed on to talk.

"She's duplicitous," Liz later told a friend. "She would say or do anything that would forward her ambitions. She can look you straight in the eye and lie, and sort of not know she's lying. 'Lying' isn't a sufficient word; it's distortion of the truth to fit her case."

Hillary understood that it was very important to keep Pat on her side," said one of Moynihan's chief political strategists. "Otherwise, Pat could be fatal to her, if he came out and said he didn't back her."

Mandy Grunwald did a masterly job of preventing that from happening. She used her longstanding friendship with Liz and Pat to persuade them to support Hillary. Mandy asked for one further favor: would Liz make the Moynihans' farm in Pindars Corners, in the rolling hills of New York's Delaware County, available for the kickoff of Hillary's listening tour?

"Liz Moynihan had her doubts about the wisdom of allowing [Hillary] to use her home as the launch pad for a Senate campaign," wrote Godfrey Hodgson. "She drew the fine at some of the suggestions made by the First Lady's overly enthusiastic handlers. They wanted a rope line to keep the media at a distance.

"'No rope line,' Liz said with finality, and disappeared into the house, ostensibly to telephone her husband. She emerged, quoting him as saying, 'You'll have to find another farm!' Liz went on, 'I've never made a circus for Pat, and I'm not going to make a circus for her.' Besides, she added shrewdly, you don't want to dilute the [Moynihan] image. 'It's worth a million votes upstate.'"

In the end, however, Liz relented, and on a hot, sunny day in July, Pindars Corners became the bucolic setting for Hillary's announcement of her listening tour. Some 300 journalists, from as far away as Japan, descended on the place. As one reporter noted, they spilled more ink and used up more airtime on Hillary "than the presidential race, Kosovo, the stock market, the World Series and Ricky Martin combined."

Television camera crews faced the path that led to a white wooden schoolhouse with a potbellied stove, where Moynihan wrote his books. After a while the door of the schoolhouse opened, and Hillary and Moynihan emerged. As the cameras rolled, the two politicians strolled down the hill to the microphones. Hillary, dressed in a navy pantsuit, had on her best Mona Lisa smile. Moynihan, in an oxford button-down shirt and white pants, looked gaunt and frail, and not at all enthusiastic about being thrust into the center ring of a political circus.

The deep ambivalence that Moynihan felt toward Hillary became immediately apparent when he stepped in front of the microphones and plunged into a long, rambling discourse about the schoolhouse behind him and its history. Then he caught himself. "God, I almost forgot," he said with a mischievous grin after introducing Mrs. Clinton. "I'm here to say that I hope she will go all the way. I mean to go all the way with her. I think she's going to win. I think it's going to be wonderful for New York."

In anticipation of tough questions from the press, Hillary tried to use some humor, saying, "I'm really excited about being able to take these long, beautiful summer days and, you know, kind of at a leisurely pace with, you know, a few hundred of you, to travel from place to place and meet people."

Inside the Moynihan farmhouse, Liz stood at a window, marveling at the dozens of TV satellite trucks and buses, the miles of cable, and local kids hawking lemonade to the reporters and onlookers. The scene reminded her of the Steven Spielberg science-fiction movie E.T.

After a moment, Liz turned to the man standing next to her, Moynihan's chief of staff, Tony Bullock. "Tony," she said, "look at this! The Martians have landed!"

In June, Harold Ickes convened a meeting at a New York Sheraton Hotel. The dozen or so people crowded into the conference room made up a Who's Who of Friends of Bill and Hillary. A product of Manhattan's Upper West Side Democratic clubhouse politics, Ickes had been Bill Clinton's manager at the 1992 Democratic National Convention in New York, at which Clinton was nominated for president. He then served as White House deputy chief of staff in the first Clinton administration.

The core group assembled that day included several battle-scarred veterans of past New Yak political wars, including Samara Rifkin, who was in charge of setting up Hillary's Manhattan office. This New York nucleus was augmented by a number of out-of-staters, who were part of the Clintons' far-flung political and fund-raising apparatus. Harold Ickes had invited his favorite fund-raising sidekick, Laura Hartigan, who was the head of the Los Angeles-based consulting firm of Hartigan & Associates.

A tall, strikingly attractive blonde, Laura Hartigan had earned a controversial reputation as the finance director of the 1996 Clinton-Gore campaign. She and her then boss, Terry McAuliffe, who would later become head of the Democratic National Committee, were questioned after the election by federal prosecutors and Senate investigators about their suspected role in an unlawful fund-raising scheme. It was alleged that McAuliffe and Hartigan had tried to arrange to funnel illegal contributions to Teamsters president Ron Carey's re-election campaign in exchange for about $ 1 million in Teamsters contributions to state and local Democratic Party coffers.

"Every morning I open the papers to find out how Hillary's shot herself in the foot today."

Although Laura Hartigan was never charged with any wrongdoing, she did not dispute the existence of a memo sent out by her campaign office listing specific states where the Teamsters should direct funds. Nor, for that matter, did anyone ever doubt that Laura Hartigan's longtime mentor, Harold Ickes—who, as a lawyer, was linked to an unsavory labor union— was up to his eyeballs in questionable fund-raising practices during the Clinton-Gore re-election campaign.

Though the Senate election was still nearly a year and a half away—and Hillary had yet to issue a formal declaration of her intent to run—Ickes and company had already signed up Gabrielle Fialkoff, a former fund-raiser for Pat t Moynihan, to aid in the money chase. They had also drafted a month-by-month campaign budget, and were now ready to turn their attention to the crucial matter of creating a war chest.

"It was clear from the way Harold ran the meeting— and the fact that he brought along Laura Hartigan—that he was going to be in total charge of Hillary's Senate campaign," said a New York-based politico who was there. "I found it strange that Hillary, who was going to face the sensitive carpetbagger issue, would choose Harold, who now made his headquarters in Washington, D.C., not in New York, and was seriously contaminated by his alleged connections to so many financial scandals.

"Let's face it," this person continued, "Harold might be a brilliant political strategist, but he's not a good guy. And he hated Bill Clinton for having fired him [in the wake of the 1996 campaign-finance scandals, in which Ickes was implicated]. True, Hillary had conspired with Bill behind the scenes to fire Harold, but she pretended otherwise, and was able to good-cop Harold back into her camp for the Senate race. That this seriously compromised guy was her guru said an awful lot about the character of Hillary Clinton."

After everyone had a chance to get re-acquainted and settle down, Ickes handed out a sheaf of papers labeled "National Fundraising Strategy Plan Working Document," which, on subsequent pages, bore the instruction, "Confidential—Not for Distribution." The room fell silent, except for the rustle of paper.

A quick scan of the document revealed two major surprises. First, the plan set a staggering goal of $25 million in direct contributions, or so-called hard money, to the candidate. This was a huge amount for a Senate race. Second—and perhaps even more striking—the plan anticipated that as much as two-thirds of the money would come from outside New York.

As far as Ickes was concerned, this was not going to be a local race. From the get-go, it would be treated as a national effort. The atmosphere in the room crackled with excitement. Ickes seemed intent on turning Hillary's Senate campaign into a dry run for the White House.

During the meeting, Ickes got into a nasty argument with Susan Thomases. For a time back in the 1960s and 1970s, Ickes and Thomases had been lovers; they had lived together and worked together on Senator Eugene McCarthy's presidential bid. Like Ickes, Thomases was a bred-in-the-bone leftist, a screamer of obscenities, and a fearless practitioner of the politics of intimidation.

"I have a very strong reality principle, and it's one of the things that gets my mouth in trouble and gets me in trouble—from [the media's] perspective, gets me in trouble," Thomases once told a reporter. "I think, of course, it's the source of my strength."

Others begged to differ. In their view, Thomases' strength derived from her special relationship with Hillary, which had been forged back in Arkansas during Bill Clinton's unsuccessful 1974 campaign for Congress.

Over the years, Thomases had become Hillary's best friend, alter ego, and chief enforcer. She looked the part. With her frizzy salt-and-pepper hair, frumpy clothes, down-at-the-heels shoes, and expletive-laden vocabulary, Thomases was just the kind of tough, strong-willed, ideologically passionate woman Hillary had always admired. And her admiration was only heightened by the way in which Thomases coped with her medical condition, multiple sclerosis, a progressive and incurable disease.

"They had begun on the same track," noted David Brock, one of Hillary's biographers, in his book The Seduction of Hillary Rodham. "Both were the only daughters in families of boys, both had strong mothers. Hillary went to Wellesley and Yale, and Thomases attended Connecticut College and Columbia University Law School. But by the 1980s, Thomases was a high-powered New York lawyer making a half million dollars a year, while Hillary's earning power was substantially eroded by her political work for Bill.

"Thomases lived on Park Avenue, had a summer house in Newport, Rhode Island, and was on a first-name basis with the top political figures in New York. She was living in a sophisticated world that Hillary, tied down in Little Rock, could engage with only at a distance. Thomases was anything but the traditional political wife: she kept her own name after marrying a carpenter-turned-artist, [the late] William Bettridge, who stayed home and took on many of the child-care responsibilities."

During the 1992 presidential campaign, Hillary backed the appointment of Thomases as Bill Clinton's chief scheduler, a role that put her in charge of access to the candidate. Since then, Thomases had become what one reporter called "the Clinton administration's King Kong Kibitzer—whose advice on everything from personnel to policy resounds like a mighty roar through the halls of the West Wing."

From the beginning of the campaign, Harold Ickes and Susan Thomases wrestled with a perplexing problem. A must-win demographic group—observant Jews—did not like their candidate.

Normally, a Democratic candidate running a statewide race in New York needed two-thirds of the Jewish vote to offset the traditional Republican turnout in the suburbs. But Hillary's likely Republican opponent, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, was quite popular with observant Jews. He had reduced crime in Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods and made New York City a cleaner, safer, more civilized place in which to live and earn a living.

Giuliani won the hearts and minds of many Jews by heaping ridicule and contempt on one of their arch-enemies: the late Yasser Arafat, the Palestine Liberation Organization leader. In a popular move, the feisty mayor barred the terrorist leader from a concert at Lincoln Center marking the United Nations' 50th anniversary.

Even more disturbing in the eyes of Ickes and Thomases was the negative reaction of many college-educated women—and not just Republican women—to Hillary's candidacy. Indeed, her biggest detractors were found among women who resembled Hillary the most—white, professional, upper-middle-class baby-boomers.

As Hillary began to gain some political traction, her "woman problem," as it came to be known inside the campaign, continued to bedevil Ickes and Thomases. Finally, after months of dithering, they commissioned a series of focus groups made up of suburban women. When they viewed the tapes from these focus groups, they became deeply alarmed. Asked what they thought of Hillary Clinton, the suburban women said:

"Very controlling."

"Self-serving. She's very cunning, independent."

"She's cold."

"You get the sense that she doesn't think like a woman. She thinks like a man."

What did women want from Hillary? Ickes and Thomases weren't sure, but they knew they had to "warm up" their candidate as quickly as possible. They asked Mandy Grunwald to put together a speakers' bureau, whose job would be to win over women voters. The bureau was called Hillary's Advocates, and it was run by Ann Lewis, a Democratic Party activist and the sister of Barney Frank, the congressman from Massachusetts. Ann Lewis gave Hillary's Advocates a set of talking points, which were aimed in large part at portraying Hillary as a victim of male sexism:

Probably the most important issue to address can be illustrated by one guest's remark—"Something is stopping me from trusting or supporting [Hillary]."

What seems to address this "something" successfully is the realization that more is being asked of her because she is a woman than would be asked of a man in her position—she has to know what it's like to work and change a diaper but he doesn't, she has to justify her marriage, her "realness" but he doesn't.

At some point in the campaign, Harold Ickes realized that his biggest problem—bigger than women, bigger than Jews—was Hillary Clinton herself.

After years of stumping for her husband, Hillary, who had once denigrated moms who "bake cookies and make tea" and complained of a "vast right-wing conspiracy," still had a perverse talent for putting her foot in her mouth.

Ickes's instinct was to keep her as far from the press as possible. Her media advisers regularly informed television camera crews to be prepared for "a 70-foot throw"— campaign-speak, as the New York Post's Gersh Kuntzman helpfully pointed out, for "the distance reporters will be kept from the candidate."

"She's been insulated in the cocoon so long that she's definitely uncomfortable," said WNBC's Gabe Pressman, the dean of the New York press corps. "She's not used to hugs and it shows. But she can learn to do it, just like that other alleged carpetbagger, Bobby Kennedy. He was stiff when he started, too."

But "stiff" didn't even begin to describe Hillary Clinton's clumsiness as a candidate. "Ineptness" and "incompetence" were more like it. In fact, Hillary made so many gaffes during her first few months on the campaign trail that people began to wonder if she was cut out for the rough-and-tumble of electoral politics.

When the Yankees won the World Series and went to the White House, Manager Joe Torre presented Hillary with a team cap. She promptly put it on and declared that she had "always been a big Yankees fan." After the laughter died down in the saloons and taverns throughout New York City, Hillary looked more like an out-of-touch carpetbagger than ever.

When President Clinton granted pardons to 16 imprisoned Puerto Rican terrorists in an obvious bid to help his wife win New "York's two million Hispanic votes, Hillary said she had not been involved in the decision—a claim that almost no one believed. In fact, Hillary's brother Hugh Rodham and her campaign treasurer, William Cunningham III, had both lobbied to win other pardons from the president.

When Pardongate became yet another Clinton scandal, Hillary spoke out against the clemency decision. But her failure to alert Latino officials in advance of her about-face prompted howls of protest from Fernando Ferrer, the Bronx borough president and the highest-ranking Puerto Rican official in the city.

When Hillary made the obligatory trip W to Israel to win Jewish votes back home, she went to the Palestinian-controlled city of Ramallah. There she appeared onstage with Yasser Arafat's wife, Suha, who made the outrageous charge that Israel was poisoning Palestinian women and children with toxic gas. At the end of Mrs. Arafat's speech, Hillary marched to the podium and gave Suha Arafat a big hug and kiss. The photo of the two women kissing, which was played around the world, sowed serious doubts about Hillary in the minds of many Jewish voters.

When Hillary realized that she had gotten herself in a jam with Jewish voters, she suddenly turned up a long-lost Jewish step-grandfather—an announcement that was dismissed by many cynical New York voters as an example of her pandering.

When Mayor Giuliani attacked the Brooklyn Museum of Art for an exhibition drawn from the Charles Saatchi collection, which included a painting of the Virgin Mary with breasts made of dried elephant dung, Hillary did not rush forward to defend the museum's First Amendment rights. Trying to have it both ways with voters, she said she found the show "deeply offensive," but believed shutting it down, as Giuliani proposed, was "a very wrong response." Her response made her look like a woman without any convictions.

When a reporter asked Hillary if she planned to march in the Saint Patrick's Day Parade, she promptly responded, "I sure hope to!" Those four words, perhaps more than any others, revealed Hillary's ignorance of New York's convoluted politics. For years Democrats had avoided the parade because the Ancient Order of Hibernians refused to allow gays and lesbians to march under their own banner. By saying she would march, Hillary offended one of her core constituencies—homosexuals.

"Independently, the mistakes are meaningless," said Democratic political consultant George Arzt. "Cumulatively, I think they are very damaging.... She doesn't have the instincts yet of a New York pol. It's like a quarterback not reading the defenses."

"Here's a woman I've admired since '92 for being a strong, smart feminist," wrote New York Daily News columnist Lenore Skenazy. "A woman who knew her own mind—and spoke it. Now I wonder who's at the controls. Every morning I open the papers to find out how she's shot herself in the foot today. With a .38? An Uzi? A small grenade? The gaffes just won't stop."

"That odd sound you hear," wrote Noemie Emery in the National Review, "is a legend imploding; the short, saintly stardom of Hillary Clinton, as it sputters to a halt."

On February 4, 2000, Bill Clinton and a small group of aides gathered in the White House movie theater to help Hillary rehearse her formal-announcement speech. Standing at the lectern, shifting uncomfortably from foot to foot, Hillary began reading haltingly from her draft speech.

All of a sudden the president jumped up from his seat. "You need to say why you're running here and now!" he shouted.

"Because I'm a masochist," Hillary shot back, half in jest.

The president looked down at the copy of the draft in his hand and began re-arranging the order of the paragraphs.

"She'll announce," he said. "They'll cheer and dance around. That's fine. Why is she doing it? Why not Illinois, Arkansas, Alaska? Why not rake in some dough? Why ask to be trashed right now? What I wish you could do, Hillary, is a sentence here: 'The overwhelming reason is that I don't want to give up my life in public service.' "

Bill Clinton refused to ease up on his wife. He telephoned Harold Ickes, Susan Thomases, and Mandy Grunwald several times a day, asking for updates on how Hillary was doing. He kibitzed the campaign.He made sure that he was involved in every aspect of decision-making, including the most important part of all: fund-raising.

"Past presidents were content selling ambassadorships," The New York Times's Maureen Dowd wrote in September 2000. "The Clintons may as well have listed the Lincoln Bedroom on eBay. Lately, they have packed state dinners with politicians, donors and journalists they hope will boost Mrs. Clinton's Senate campaign. They even put up circus tents on the lawn for the India state dinner. They have to jam them in fast—only 118 days left to peddle the People's House."

About three-quarters of the way through the campaign, Hillary finally began to get the hang of things. In part, aides attributed the turnaround to Hillary's considerable intelligence. Tony Bullock, Pat Moynihan's chief of staff, found that Hillary displayed an awesome ability to absorb complex information.

"She would call me to discuss the Brookhaven National Lab, the controversial Peace Bridge, in Buffalo, and the Lake Onondaga pollution-cleanup issue," Bullock told me. "She would get into these details, learn these issues, and then her audiences would be blown away by how she knew more than they did about their local issues."

At the start of the campaign Hillary had come off poorly in small groups. Now she seemed more at ease schmoozing potential donors. Gone was the left-wing Hillary, the gender feminist who sounded to many people like a radical bomb thrower. In her place was the newly minted Hillary, a kinder, gentler, family-oriented candidate who championed such issues as children's mental health.

As part of their campaign strategy, Ickes and company confronted the frequently heard question: Why do people dislike Hillary so much?

Their answer, shared by many: A strong woman threatens men.

Of course, it wasn't only men who disliked Hillary; she had even more trouble winning the trust and support of white, suburban women. Still, the notion advanced by Ickes and company that Hillary threatened insecure men was an effective ploy. It resonated with many successful women, who secretly worried that they, too, might intimidate their husbands, boyfriends, and male co-workers. Such women identified with Hillary, because they knew how hard it was to juggle career, family, and femininity.

Furthermore, Hillary's supporters accused her critics of using a double standard when they criticized her for being overly ambitious. Why should ambition be considered a virtue in men but a vice in women? they asked. Why were boys encouraged to dream of growing up to become president but girls were not? Why was ambition in Hillary any different from, say, ambition in Rudy Giuliani or, for that matter, in any male candidate?

These were all legitimate questions. But they totally missed the point. The objection that people had to Hillary was not that she was ambitious, or that she pursued power. Nowadays, people applauded powerful women in every field of endeavor. Such women had earned their place in the sun. The problem with Hillary was that she behaved as though she were entitled to power. She had been brought up by parents who taught her that nothing was beyond her. It was Hillary's exaggerated sense of her own importance and her feelings of superiority—not her gender—that turned people off. People hesitated to vote for a woman like Hillary not because she was a woman, but because she acted as though she had a divine right to rule.

Where was Pat?

With the exception of one campaign commercial on Hillary's behalf and an appearance at the convention that nominated her for senator, Pat Moynihan had been virtually invisible since the satellite trucks and television cameras left his farm at Pindars Corners several months before.

That did not come as much of a surprise to those who knew of Pat and Liz Moynihan's standoffish attitude toward Hillary. And yet Ickes and company reacted to the Moynihan snub with deep concern. They had been counting on Moynihan to act as a counterweight to Hillary's opponent, Rudolph Giuliani. After all, Moynihan was popular with some of the same groups that made up Giuliani's base, especially IrishAmericans and Italian-Americans.

Even more important, Jews adored Pat Moynihan, and Hillary needed all the help she could get with Jewish voters. Indeed, when it was revealed in the Jewish New York newspaper Forward that she had attended secret fund-raisers sponsored by two Arab businessmen, Hillary realized she had painted herself into a corner. Next it was reported that she was the beneficiary of a fund-raiser given by a Muslim group that called for armed force against Israel.

Astute political observers detected the fingerprints of Bill Clinton on the campaign's Arab strategy. They pointed out that one Palestinian-born businessman, Hani Masri, who helped raise $50,000 for Hillary's campaign, was simultaneously in line for a $60 million government loan.

That Hillary was courting a radical Muslim group did not remain secret for long. And when she showed up to march in the annual Israel Day Parade, the crowds roundly booed her. Worse, she was booed off the stage during a "Solidarity for Israel" rally in front of the Israeli Consulate in New York.

On the morning of May 19, shortly after she was formally nominated as her party's standard-bearer, Hillary woke to discover that her need for Pat Moynihan's support had been radically diminished. For on that day—and with just six months to go until the election—Rudy Giuliani announced that he had prostate cancer and was bowing out of the race.

In Rudy's place, the Republican Party turned to a young Long Island congressman by the name of Rick Lazio. Though he was likable and telegenic, Lazio was never able to mount a campaign to match Hillary's. Nor did Lazio have time to develop an effective ground game. He failed to show up at county fairs in upstate New York and spent all his resources on TV commercials and raising hard money.

Many of Lazio's consultants came from out of state and seemed intent on running what was more a hate campaign than a political campaign. What's more, they seemed obsessed with Hillary's ready access to soft money. In response, Hillary made all the appropriate noises about the toxic effects of soft money on politics. Meanwhile, her Machiavellian adviser, Harold Ickes, was raising soft money as fast as he could.

Lazio entered the first of three candidates' debates with an ill-conceived plan to embarrass Hillary. He told the moderator, Tim Russert, "Mrs. Clinton has been airing millions of dollars in soft-money ads. It's the height of hypocrisy to talk about soft money when she's been raising soft money by the bucket loads out in Hollywood and spending all that money on negative advertising." Then he produced a piece of paper: "Right here. Here it is. Let's sign it. It's the New York Freedom from Soft Money Pact. I signed it. We can both sit down together." Lazio left his podium, walked across to Hillary Clinton, and waved the piece of paper in her face, demanding, "Right here, sign it right now!"

Hillary refused, and many of the women watching the debate on television recoiled at Lazio's bullying tactics. Lazio, they felt, had "invaded Hillary's space."

After that debate, Hillary's transformation from political troublemaker into sympathetic victim was complete. Her supporters flocked to the polls, and on Election Night in November 2000 she won by a landslide: 55 percent to Lazio's 43 percent.

She was now Senator-Elect Hillary Rodham Clinton. Her husband was soon to be former president Bill Clinton. After nearly three decades of playing a supporting role for Bill, it was now Hillary's turn to step into the political spotlight.

She looked different now—more the way Oshe had when she was a frumpy Yale law student than when she was a glammed-up First Lady. She stopped wearing pastel pantsuits and adopted black as her noncolor color. Her hair, which her stylist used to tease into a mighty blond helmet, hung limp around her temples. She was too intent on serving her constituents back home and too focused on fetching coffee for her male colleagues in the Senate to take time out for such frivolous matters as personal grooming.

She put in 12- to 14-hour days. She trudged along the broad hallways on Capitol Hill, her low-heeled shoes echoing off the hard marble floor, a cell phone stuck to her ear, a sheaf of documents tucked under her arm. She attended one interminable committee meeting after another, stifling yawns of boredom. She was willing to take on any assignment, and won the Senate's Golden Gavel Award for presiding over that body (usually when it was nearly empty) more than 100 hours.

She was a woman in perpetual motion. According to people who visited her in her office, she looked like a zombie—baggy-eyed, zoned out for lack of sleep.

Her large L-shaped suite, on the fourth floor of the Russell Senate Office Building, had once belonged to Pat Moynihan. Now the furniture, wallpaper, carpeting, and curtains all reeked of Kaki Hockersmith, the Arkansas decorator the Clintons had employed to do their rooms in the White House.

One day, Moynihan dropped by for a visit. He had lost more weight and looked sickly. (He would be dead by the spring of 2003.) He glanced around his old office and remarked wryly, "The place looks a lot more yellow."

Yellow was also the dominant color scheme at Whitehaven, the stately brick mansion near Washington's Embassy Row that served as Hillary's White House in exile. For the job of decorating Whitehaven, Hillary picked the firm of BrownDavis Interiors, which had recently renovated the British Embassy. Architectural Digest ranked Brown-Davis among the top 100 intenor designers and architects in America.

When guests arrived at Whitehaven for one of Hillary's fund-raisers, they stepped through a red door into a foyer with stenciled floors. There they were greeted by a battalion of neatly dressed staffers and escorted directly outdoors to a tent in the garden, where they joined other donors and white-coated waiters. No one was allowed to wander around the house; if they had, they might have noticed that, among all the silver-framed photos, there were no recent pictures of Hillary with Bill.

Hillary sometimes produced back-to-back fund-raisers on the same night. In her first 21 months in office, she held 46 fundraisers at Whitehaven, an unheard-of pace.

Donors who were rich enough to pony up $25,000 were treated to private little dinners with Hillary herself. Several couples were ushered into Whitehaven's large dining room, where they were seated in yellow chairs with pink backs. Hillary presided from the head of the table.

These dinners reminded some old-timers of the days back in the 1980s and early 1990s when the late Pamela Harriman held court at her Washington mansion. Like Pamela, Hillary turned her home into the Democratic Party's Fund-Raising Central.

Of course, she had the perfect teacher: Bill Clinton had turned political fund-raising into an art form. The excesses perpetrated by Harold Ickes in the president's name had led to the campaign-finance scandals of the 1996 election. But Hillary kept Ickes on as her fund-raiser in chief.

Despite the effort she and Ickes put into fund-raising, money was really never a problem for Hillary. Thanks to an organization called Friends of Hillary, she could easily raise all the funds she needed for her 2006 Senate re-election campaign. Hillary and Ickes spent most of their energy raising money for other Democrats.

"She can give $10,000 to a candidate through her multimillion-dollar leadership political action committee, HILLPAC," noted a leading expert on the campaign-finance laws, "but if she has a fund-raiser at her home, she can raise hundreds of thousands of dollars in one night for a Democratic candidate. No one can do that as effectively as she can. Who isn't going to show up if Hillary Clinton invites you to her home?

"That's what makes Hillary different from other Democrats," this person continued. "And that's the key to her strategy over the next few years, building relationships, establishing a firm control over the machinery of the state parties outside New York."

By 2003, Hillary had begun to rival Bill Clinton as her party's most sought-after fundraiser. And she accomplished that by imitating Bill's three-pronged approach to raising money: Hollywood celebrities, liberal businessmen, and female activists.

"She's more of a star than the other 99 of us combined," said Senator Mark Dayton, of Minnesota, a Democratic recipient of Hillary's generosity.

The fine hand of Harold Ickes could be detected behind Hillary's money-raising activities. As Eliza Newlin Carney wrote in the National Journal:

The ethical problems that earned the Clintons such notoriety at the White House may come to dog Hillary Clinton's massive fundraising operation, particularly as it attracts more scrutiny. As a candidate in 2000 and as a senator, Clinton has moved vast sums of money around in a complicated array of interlocking and sometimes controversial campaign accounts— leadership PACS, nonfederal accounts, joint committees with the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee....

The 2002 campaign finance law has unquestionably drained the major party committees of both cash and influence. The new power centers are now outside interest groups and individual office-holders, such as Clinton, who can motivate low-dollar donors by virtue of their ideological appeal or their celebrity. With its vast staff budget, and campaign coffers, Clinton's political organization has begun to assume a quasi-party status.

Thus, Hillary emerged as the 800-pound gorilla in her party. Quinnipiac University polls put her ahead of the entire field of candidates for the 2004 Democratic presidential nomination.

"If she even let herself be talked about seriously, she'd be the one to beat among the Democrats [in 2004] and she could raise zillions of dollars," said Quinnipiac pollster Maurice Carroll. "I can't figure out who in the bunch of them could beat her."

Bill Clinton was eager for Hillary to throw her hat into the ring for the nomination in 2004, but Hillary decided to pass on that race in the belief that (a) she needed more time to establish a record, and (b) George W. Bush was unbeatable as a wartime president. Instead, she decided the time had come for her to move into the next stage of her Senate career.

"She spent the first two years in a learning process ... not only the rules of the Senate, but the traditions of how things should be handled here," John Breaux, a moderate Democrat from Louisiana, said shortly before he retired from the Senate. "She was very careful and more restricted. Now she's moving into a second stage, being more out-front, more visible and more available to articulate issues."

In this second stage, Hillary was laying the foundation for a likely run for the White House in 2008. She was transforming herself before the eyes of the fascinated public from the old, radical Hillary into the new, moderate Hillary. Not since Richard Nixon had a politician attempted such a dramatic makeover. The question remained: Would voters buy this "new Hillary"?

Excerpted from The Truth About Hillary: What She Knew, When She Knew It, and How Far She'll Go to Become President, by Edward Klein, to be published this month by Sentinel; © 2005 by the author.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now