Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNot only is National Public Radio a last bastion of calm, reliable reporting, it reaches more people than Fox News. But as NPR celebrates its 40th anniversary, it suffers from one glaring bias: against the author

December 2010 James WolcottNot only is National Public Radio a last bastion of calm, reliable reporting, it reaches more people than Fox News. But as NPR celebrates its 40th anniversary, it suffers from one glaring bias: against the author

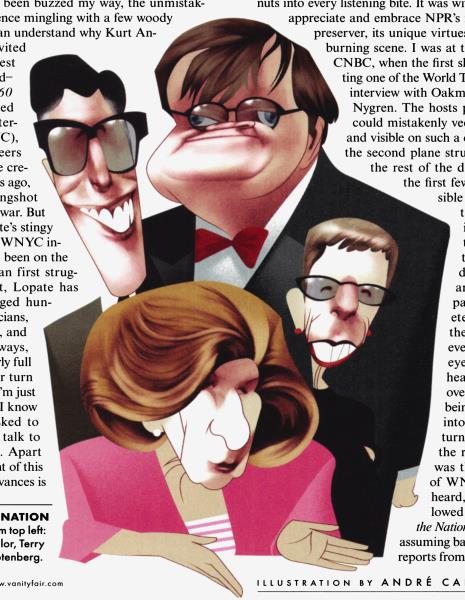

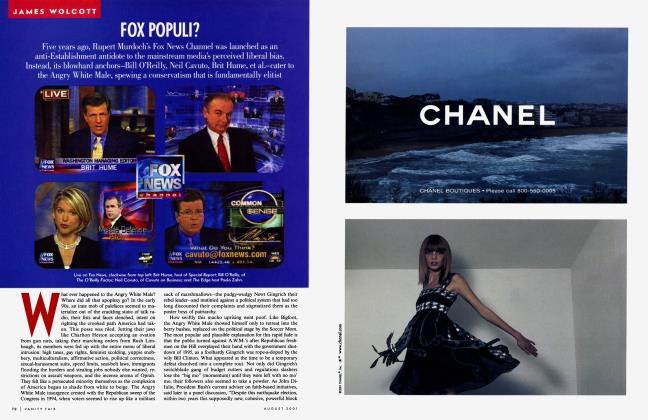

December 2010 James Wolcott VOICES OF A NATION Clockwise from top left: Ira Glass, Garrison Keillor, Terry Gross, and Nina Totenberg.

VOICES OF A NATION Clockwise from top left: Ira Glass, Garrison Keillor, Terry Gross, and Nina Totenberg.

I hear a grudge against National Public Radio, a grudge that has grown over the years into quite a bitter lad. Precariously propping up the collective I.Q. of the country with reliable reporting, wry commentary, and whimsical humor (which can really get on your nerves if you're not in the mood), NPR may be a beloved institution to millions of listeners, a lighthouse of searching calm in a sea of crazy, a warm companion on a rainy day—but not to me. Personally, professionally, NPR has never done me a lick of good. I've brought out a novel and a book about the media, and with both NPR shut the chapel door in my face, while just about every other writer I know has gotten their ego scalp-massaged, with ample opportunity to recount the "genesis" of their latest work without the interviewer's eyes wandering all over the racetrack. "This is Fresh Air. I'm Terry Gross." Fresh air, how sweet it must taste. Stale rejection straight from the aerosol can is what's been buzzed my way, the unmistakable scent of indifference mingling with a few woody notes of "scram." 1 can understand why Kurt Andersen has never invited me aboard as a guest for his Peabody Award-winning Studio 360 program (co-produced by Public Radio International and WNYC), which each week peers under the hood of the creative mind: a few years ago, he and I traded slingshot pebbles over the Iraq war. But what's Leonard Lopate's stingy excuse? The host of a WNYC interview show that has been on the air since unibrow man first struggled to walk upright, Lopate has knowledgeably engaged hundreds of writers, musicians, journalists, architects, and distinguished stowaways, his greenroom regularly full of guests waiting their turn for flu shots, and yet I'm just about the only writer I know who's never been asked to lay down a little hep talk to all those square cats. Apart from venting, the point of this Festivus litany of grievances is to say that, despite all the nothing NPR has done for me, I still donate money to it! They ask and I give. Which makes me a masochist, a patsy, or a true liberal, which in many people's minds are interchangeable terms—redundancies. And I barely listen to NPR when I'm in New York, finding it too laxative, too self-effacing.

It isn't until I leave New York City and turn on the car radio or the creaky one in the motel room that NPR's distinctive, coherent, cadenced qualities press to the forefront: its commitment to informing and entertaining an educated audience like adults speaking to other adults while every other hothead and hysteric on the dial hops up and down on the pogo stick of the outrage du jour. Or, conversely, reaches out from the speaker to soothe thy troubled brow, a ghostly comforter which turns out to be the radio ministry of a Jesus station requesting a prayer offering payable by check or credit card. Right-wing or religious, radio packs a ton of nuts into every listening bite. It was with 9/11 that I came to fully appreciate and embrace NPR's irreplaceability as a sanity preserver, its unique virtues as first responder on the burning scene. I was at the Jersey Shore, watching CNBC, when the first sketchy news of a plane hitting one of the World Trade towers interrupted an interview with Oakmark portfolio manager Bill Nygren. The hosts puzzled over how a plane could mistakenly veer into something that tall and visible on such a clear, bright morning; then the second plane struck the second tower, and the rest of the decade was defined. After the first few hours, it became impossible to take the castle fall of the imploding towers being replayed in a loop at the corner of the screen, the coffee grinder of tragic destruction cranked over and over again like a compact edition of Nietzsche's eternal recurrence through the nickelodeon, with whatever rumors and reports and eyewitness testimonies we heard from the audio being overpowered by what we were being hypnotically shown—fed into our fear lobes. Finally, I turned off the TV, switched on the radio, and found NPR. It was the unmelodramatic voice of WNYC's Mark Hilan I first heard, playing air controller, followed by Neal Conan's Talk of the Nation and All Things Considered assuming battle stations, fielding phone reports from eyewitnesses and patching expert analysis into a rough pattern-recognition field without allowing the chaos and trauma of the attacks to rhetorically flame-curl into Armageddon talk.

It will be no surprise that This Is NPR (Chronicle), an oral-history scrapbook of the network from its first baby steps in the 70s to its multi-media omnipresence today, published to commemorate NPR's 40th anniversary, goes light on gossip, recriminations, and lurid lore, resisting the temptation to pander to our vile curiosity about what our favorite personalities get up to when the ON AIR sign is switched off and their animal passions answer the torrid drumbeat of desire. From NPR alumni such as Susan Stamberg to current stalwarts such as Cokie Roberts, everybody reminiscing in This Is NPR acts abnormally nice, unless they're not acting, simply behaving as responsible journalists did before cable news turned so many of them into performing seals and Pez dispensers—yes, I'm pointing the finger of justice at you, Howard Fineman! And you too, Mike Allen of Politico!

Unlike nearly all the rest of talk radio, which divides civilization into us and our Churchillian allies and Everybody Else (ungrateful bastards who haven't thanked us in the last five minutes for winning World War II), NPR is cognizant of a whole world out there that isn't the United States and is worth knowing, even if we're not dropping bombs on them at the moment.

The multiculturalism that NPR practices better than anybody (and not just because hardly anybody else is bothering to try) is flexed in the catholic reach of its foreign coverage, which in its infancy meant calling on the resources of The Christian Science Monitor, which was, This Is NPR reminds us, "a big, flourishing paper in the '70s, with cadres of reporters stationed all over the world." Those were the days. As newspapers and television networks fold their foreign bureaus, retire their overseas correspondents, and rely on freelance stringers and Skype, today NPR is just about the last outfit that hasn't retrenched and retreated from Marshall McLuhan's global village but instead has extended its feelers to tap even the faintest faraway dot on the map with a moving story to tell, navigating near-impossible terrain if necessary. This can lead to borderline self-parody, too many dispatches from remote villages about the dying native craft of flute-making narrated by a correspondent who sounds as if s/he majored in empathy at Deepak Chopra Junior College, a mourning dove with a microphone. But the beauty of radio is that the ambience of other countries, other cultures, fills the sonic background with no camera eye imposing a single dominant message-image (a close-up of scorched belongings to signify the ravages of war), and no reporter standing in the foreground, colonizing the frame with a faceful of concern. Our eyes un-commandeered by radio, we're able to take in so much more than the words alone are telling, which isn't to say that sometimes the local color isn't laid on a little thick.

IT WILL BE NO SURPRISE THAT THIS IS NPR GOES LIGHT ON GOSSIP AND LURID LORE.

NPR's nurturing Earth Motherliness was hilariously spoofed in Saturday Night Lives recurring "Delicious Dish" sketches, in which the hosts shared homespun recipes and homilies like a pair of molasses drips:

Margaret Jo McCullen (Ana Gasteyer): Now, Teri, it's Christmas season again, our favorite time of year. I'm asking Kris Kringle for a wooden bowl, some oversized index cards, and a funnel.

Teri Rialto (Molly Shannon): Ooooh, a funnel! That'll be great for funneling!

This imaginary gingerbread cottage is the gentle wing of the feminism that infuses NPR, a feminism so integrally wired into the basic circuits that it can be taken for granted, until you start listening/watching/reading someplace else. NPR was founded in the 1970s, the decade of feminist revival (what came to be called the Second Wave). A photograph in This Is NPR of the female nucleus of All Things Considered— Renee Chaney, Kati Marton, Kris Mortenson, and director Linda Wertheimer (host Susan Stamberg is shown in a separate shot)—evokes the photos of the editorial staff of Ms. magazine, which published its debut issue the same year All Things Considered was launched, and those of the feminist editors in Ellen Frankfort's memoir of The Village Voice. There's far more equal representation of women in the on-air lineup of NPR—Stamberg, Wertheimer, legal-affairs correspondent Nina Totenberg, Terry Gross, Renee Montagne, Jacki Lyden, Liane Hansen, Lynn Neary, and others—than there is in Congress, corporate boards of directors, and newspaper mastheads even at this late date. And because of this, women's issues aren't treated as parochial concerns in NPR's programming, relegated as sidebars to the clash-of-the-titans rubber-sword fights that dominate cable news and talk radio. It isn't that NPR is matriarchal but that it has dedicated itself to not being patriarchal in its outlook and presentation, stipulating from the outset that its headline voices would not resound across the fruited plains from big male bags of air sent from Mount Olympus.

The big male bags of air have been puffing at NPR from the outside, trying to blow the house down. And blowhards don't come any blowhardier than Newt Gingrich, who, upon being elected Speaker of the House following the Republican takeover of 1994, pronounced his intention "to defund the Corporation for Public Broadcasting," putting it on a starvation diet that would have wiped dozens of smaller stations off the airwaves that depended on grant moneys from the C.PB. and reduced others to skeleton crews, recounts This Is NPR. This animus against public radio first gained rhetorical traction on the right during the "Reagan Revolution," as so many ideologically driven crusades did, when NPR was christened "Radio Sandinista" for what the contra-backing Reaganites considered its slanted-left Nicaragua coverage. Gingrich railed against the elitism of NPR, proclaiming that the popularity of Rush Limbaugh represented the real face of public broadcasting, but as usual Gingrich's grandiosity was greater than his grip on political reality, and his plan fell as flat as his Speakership after the first flush of giddiness. In This Is NPR, Gingrich is quoted as graciously conceding in 2003 that he no longer considers the network an enemy within. "NPR is a lot less to the left ... or I've mellowed. Or some combination of the two." Or a third alternative: in the era of Sarah Palin Superstar, bashing NPR no longer gets the primitive, tribal juices going on the right, not with such a bumper crop of Muslims and illegal immigrants for Tea Party panderers to sink their gums into. Mosques are so much easier to hobgoblinize—to borrow one of the late William F. Buckley Jr.'s coinages—than the rest stop on the dial bringing home Morning Edition, the witty quiz show Wait, Wait... Don't Tell Mel, Ira Glass's This American Life, and the midwestern opry of Garrison Keillor's Prairie Home Companion, that church social for the socially awkward. Not to mention Car Talk. Everybody loves Car Talk, even me, and I don't drive.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now