Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowÉminence Émigrée

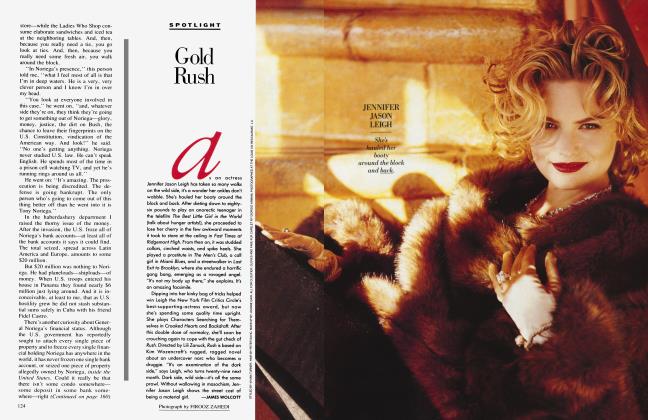

SPOTLIGHT

Like Vladimir Nabokov (a fellow countryman), Joseph Brodsky has about him a frosty summit air. His eyebrows are as proud as eagles' wings; he is his own imperium. "I find myself, as it were, on a mountain peak," he wrote in A Part of Speech. "Beyond me there is... Chronos and thin air." And snow, and barrelribbed horses, and white birches. Exiled from the Soviet Union in 1972 (his poem "To a Tyrant" is a memorable thumb in Big Brother's eye), Brodsky doesn't traffic in trivialities or the sentimental trash Nabokov called poshlust. His is a scepter'd calling. And like Nabokov, Brodsky is a cosmopolitan with pinpoint vision. The traveler in the second, post-exile, half of A Part of Speech lies awake under Venetian ceilings, climbs Mexican pyramids, and, in the north of England, attends to the dance of butterflies "below the brick wall of a dead factory." But always behind the sunlight and streams of tourists is the Russian dusk, the kingdom of the past. Farrar, Straus and Giroux this month publishes Brodsky's first book of essays, Less than One—a literary event. With its meditations on Akhmatova, Mandelstam, and Tsvetaeva and evocations of the Leningrad of his childhood, Less than One is both a tribute to the Russian dusk and the most readable packet of poet's prose since Philip Larkin's Required Writing. When the American poet Stanley Kunitz met him in Moscow in 1967, Brodsky inscribed a copy of the Leningrad Annual "From Russia with Love—Joseph Brodsky." Such love, as Less than One shows, was simpler then.

James Wolcott

"I was born and grew up in the Baltic marshland / by zinc-gray breakers that always marched on / in twos. Hence all rhymes, hence that wan flat voice / that ripples between them like hair still moist, / if it ripples at all...."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now