Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

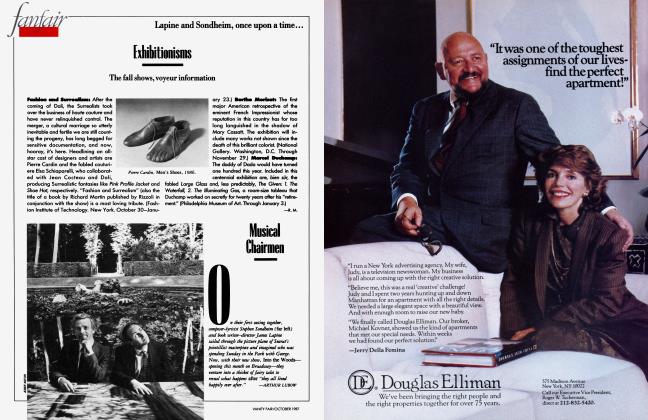

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHumorist Fran Lebowitz seems to fashion her career after Oscar Wilde's quip about putting talent into writing and saving genius for life. Writer's block has been transformed into partygoer's progress as she hobnobs with everyone from Malcolm Forbes to Mick Jagger. ARTHUR LUBOW reports

August 1985 Arthur Lubow Annie LeibovitzHumorist Fran Lebowitz seems to fashion her career after Oscar Wilde's quip about putting talent into writing and saving genius for life. Writer's block has been transformed into partygoer's progress as she hobnobs with everyone from Malcolm Forbes to Mick Jagger. ARTHUR LUBOW reports

August 1985 Arthur Lubow Annie LeibovitzMore of her evenings now require a tuxedo, and she lives in a venerable apartment building that has a name, not merely a number. Yet the fundamental things about Fran Lebowitz still apply. She is very funny. She hates to write. She likes to go out.

Because she is funny, she is asked everywhere. Rather than write, she goes. "I don't do it for any useful purpose," she says. "I'm not out gathering material. I just don't want to be at home and have to write. Painters are the ones who go out all the time. They have to, to meet the people who can afford to buy their work. Writers who say they have to go out are lying. What they're selling costs twelve dollars." Well, I point out, twenty dollars, for a book. She gobbles that quibble like a frog zapping a fly. "You see how long it's been since I've written?"

Seven years have passed since, with Metropolitan Life, Lebowitz made her spectacular debut. Reducing all issues to questions of taste, she bristled with aesthetic grievances. Against clock radios: "If I wished to be awakened by Stevie Wonder I would sleep with Stevie Wonder." Against slogan-bearing clothing: "If people don't want to listen to you, what makes you think they want to hear from your sweater?" Against "Long-sleeved T-Shirts Stenciled to Look Like Dinner Jackets and Invariably Worn by Those Who Would Have Occasion to Wear a Dinner Jacket Only While at Work." At the center of Lebowitz's philosophy was the belief that not all men are created equal. This undiluted elitism was made palatable, even charming, by its subtext: when she wasn't pronouncing that "it is not true that there is dignity in all work" or advising that "public transportation should be avoided with precisely the same zeal that one accords Herpes II," Lebowitz was scrambling for odd jobs to pay the rent on her squalid studio apartment.

Metropolitan Life permitted Lebowitz's way of life to catch up with her way of thinking. "John Leonard's review in the Times was the pivotal moment," says Laurie Col win, who signed Fran at Dutton. "The day that review appeared, the book sold out in New York." That rarest of things, a genuinely funny book, Metropolitan Life sold 100,000 hardcover copies, making the Times best-seller list; the paperback rights went for $150,000 (in those days, that could still buy an apartment). Three years later, Lebowitz published Social Studies, a second collection of essays drenched in the same snobbery. (The funniest pieces concerned the search for an acceptable apartment.) In a city with a vampirish taste for the new, it didn't create the same sensation. Still, most reviews were flattering, and not long afterward Liz Smith announced that Lebowitz had come up with a new agent—Mort Janklow—for her next work, and a title—Exterior Signs of Wealth. It would be her first novel.

People have begun to speak about Exterior Signs of Wealth the way they did about Truman Capote's perennially unfinished Unanswered Prayers. Lebowitz herself professes not to be getting anywhere with it. "The novel is what I'm doing on the side," People reported her saying. "Full-time, I'm watching daytime TV." Before acceding to be interviewed for this story (later, she de-acceded), Lebowitz thought carefully, then scheduled the meeting for the Russian Tea Room ("You can use my name, they'll give me a booth"), setting aside an hour before the driver would come to pick her up for a TV appearance that evening. She tries to bunch her obligations, she explained: "Some days I like to leave wide open, so I can stay in bed all day if I want to."

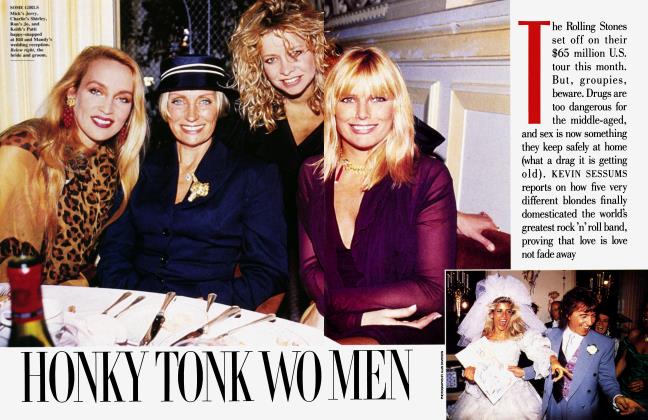

She may sound idle, but she is not. Flip from the book page to the society columns and that much becomes clear. At a Lincoln Center party for the Martha Graham company, Fran is there with her pal Paloma Picasso. At a $500-a-plate dinner for the Museum of the Moving Image, at a $100-a-cup Carnegie Hall tea for the Victorian Society, Fran stands up and is counted. There is a baby shower for Jerry Hall. (Fran is seeing more of Jerry and Mick these days.) Steve Rubell opens the latest hot club, Palladium. Jerome Robbins stages a new ballet. Martin Peretz celebrates the seventieth anniversary of The New Republic. Fernando Sanchez shows a lingerie collection. To these events, as to so many others, Fran is invited, and Fran attends. Some of her old friends wonder what's happening. "Luncheons at Le Cirque and dinners at II Monello—come on!" says one. "I think she's sort of a court jester. She's very funny, but I just wish she would put it on paper."

"Painters are the ones who go out all the time.... Writers who say they have to go out are lying."

Could it be that paper is not Lebowitz's natural medium? "She writes very slowly and very painfully," says Col win. "And she's a perfectionist. There are a lot of people with less literary integrity than Fran who would have capitalized on their reputations by rushing back to publish, even if they weren't satisfied with the work. Fran hasn't done that." But people in the writing trade assume too easily that the ambition of someone with proven literary talent is to write more. Couldn't Lebowitz's vocation lie elsewhere?

Her career began fifteen years ago in Max's Kansas City, a hangout for the druggy Warhol crowd and other participant-observers of the pop scene. Without waiting for a high-school diploma, she had escaped to New York from New Jersey, where her parents ran a furniture store. At night she went to Max's to smoke cigarettes and swap wisecracks; during the day, she peddled belts on the street or drove a taxi. Through friends at Max's who relished her wit, she began writing, always reluctantly. Before long, her column, "I Cover the Waterfront," had become a regular feature in Warhol's Interview magazine. She was then recruited by Mademoiselle to write a column, which eventually crumbled under deadline pressure. She was cajoled into putting together a book, composed mainly of those Interview and Mademoiselle pieces, and the book led to a series of interviews, TV spots, and invitations—an infinite series, or so it seems.

Max's is no more, but Interview, like its proprietor, has a knack for survival. Interview and Warhol always attracted the wealthy and the wellborn to mix with the pretty, the witty, and the weird. "At Max's we didn't think anybody was more elite than we were," recalls magazine editor and erstwhile rock-club host Danny Fields, who knows Lebowitz from the early days. But the Social Register types who went to Max's were there slumming. A decade later the president's son was writing for Interview, an unmistakable sign that like so many New York slums this one had been gentrified. The time was auspicious for Lebowitz's lapidary wit to be remounted in a more elegant, traditional setting.

The publication of Metropolitan Life elevated Lebowitz into the line of vision of the truly rich. She acquired two key admirers. Los Angeles millionaire Max Palevsky gave her a West Coast base and entree into affluent Jewish Democratic circles. Traveling with Palevsky in Israel, for instance, Lebowitz met millionaire magazine proprietor Martin Peretz (The New Republic). In New York, millionaire magazine proprietor Malcolm Forbes (Forbes) introduced Lebowitz to the Republican socialite crowd. Forbes, a fan of Metropolitan Life, invited the writer to a ballooning party at his French chateau, Balleroy, and quickly inscribed her name on his A list. "He's fascinated by Fran," says someone who knows them both. "He likes people who approach life with a different attitude, who express views different from those he normally hears." Indeed, he collects such people, along with Faberge eggs, toy soldiers and boats, and presidential autographs. Fran hit it off not just with Malcolm but with his son Christopher ("Kip"), who shares her tastes for good food and old furniture, tastes he is better situated than she to indulge.

A writer needs only pen and paper. To practice the art of conversation, one requires sterling flatware, aged Bordeaux, good cuts of meat —in short, the materials necessary to attract the right audience. The Forbeses have provided what Lebowitz needs for her art as cheerfully as the Medici quarried marble for Michelangelo.

The same themes that inform Lebowitz's writing recur in her table talk. The quest for a New York apartment, which she treated so humorously in Social Studies, is also the motif of her greatest triumph in the art of conversation. Two years ago, at a cruise-and-dine on Malcolm Forbes's yacht, the Highlander, Fran was regaling Tom Armstrong, director of the Whitney Museum, with her real-estate plight. She had finally found an acceptable apartment in a soigné midtown building, but no one would provide her with financing. Each day she drove farther into the outer boroughs, searching for a little bank that would. As Armstrong listened with the appropriate mixture of amusement and sympathy, he noticed a distinguished figure passing by. "Have you ever met Walter Wriston?" he asked Fran. She had not. "Walter," said Armstrong, "do you know Fran? She has mortgage problems." As Lebowitz filled the receptive ear of the man who was then chairman of Citicorp, Armstrong chatted warmly with Mrs. Wriston. In a few minutes, Lebowitz's artistry in conversation had accomplished what innumerable painful hours of writing could not. It had secured her a New York co-op.

If the czars of taste didn't place writing at the acme of professions, Lebowitz's career might be seen in better perspective. No one tries to pigeonhole her as a litigant, for example, even though in recent years she has devoted as much time to that pursuit as to the literary one. Admittedly, she has had less success as a litigant. Still, the same themes prevail, the same unique sensibility is at work. In her one finished courtroom piece, for instance, she again dealt with the Manhattan apartment hunt. This was in a suit she brought against Charlie Mingus's widow, who had sublet a Greenwich Village co-op to Lebowitz with, according to Fran, the option to buy. Instead, when the lease was up, Susan Mingus demanded the apartment back, and Lebowitz sued. Her case was dismissed in Manhattan Supreme Court last year, with the judge finding—ironically enough—that she should have gotten it in writing.

Conversation has been Lebowitz s lifetime work. The writing of her books is best viewed as a preparatory phase.

Lebowitz's other litigation, still incomplete, is a sort of legal diptych, which once again explores a familiar theme: the encroachments on the liberties of smokers. "When Smoke Gets in Your Eyes. . .Shut Them" was the title of Fran's essay on this topic in Social Studies. The working title of her current effort is Vershel v. Lebowitz. The first section of this piece was finished in May 1983, when a New York dentist who Lebowitz charged had slugged her in a movie theater during an argument over her smoking was acquitted. A second panel has been begun, with the dominant figures reversed. In a civil action, the dentist claims that the publicity surrounding his unjustified arrest cost him a very lucrative business contract, for which he demands compensation.

It can be argued that the cultural commissars of the sixth page of the New York Post, where Vershel v. Lebowitz has excited the greatest critical scrutiny, would have ignored the work had Lebowitz not previously established her reputation in another medium—as a writer. It might similarly be maintained that without her two books, and the resulting celebrity, Lebowitz might have had more trouble acquiring the materials necessary for her career as a conversationalist. Such observations are accurate, as far as they go. Yet isn't it more illuminating to assess Lebowitz's separate talents—to applaud her as a writer, deplore her as a litigant, and salute her as a conversationalist nonpareil?

Why not recognize conversation as an art of its own? Lebowitz apparently does. Recently she agreed to do a column for Vogue. Most columns consist of writing, but hers will be transcripts of her tape-recorded conversations. Of course, the transcripts will provide only an art-reproduction semblance of the originals, but her less privileged fans will be able to see the direction her muse is taking.

Conversation has been Lebowitz's lifetime work. The writing of her books, like the plastering of a wall for a fresco, is best viewed as a preparatory phase. "As I see it, the books are very important," says Danny Fields. "They placed her in a position where all these people are flattered to be with her." Or, as her friend Jane Rosenman remarks, "She's much more collectible now." With the drudgery behind her, she is free to dazzle. For an artist of Lebowitz's sensibility, there was always something ill-fitting about the book business. A book costs so little. Anybody can buy one, right off the rack. Instead of bemoaning Lebowitz's failure to publish, one might envy her progress. Her work is now custom-tailored, her clientele is elite. She has gone from prêt à porter to haute couture.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now