Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

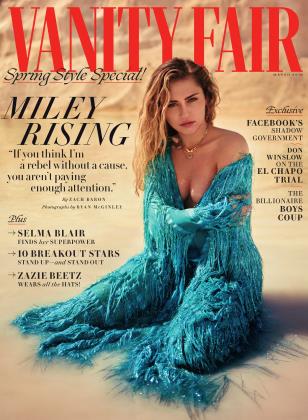

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSold as a major drug-war victory, the El Chapo trial was really just business as usual

March 2019 Don Winslow R. Kikuo JohnsonSold as a major drug-war victory, the El Chapo trial was really just business as usual

March 2019 Don Winslow R. Kikuo JohnsonIt was the trial of the century, right?

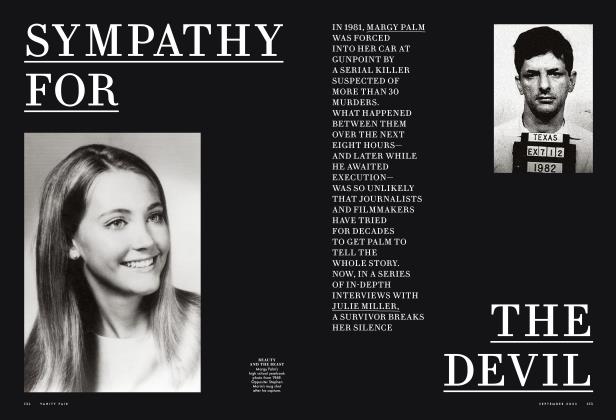

The satisfying third act in the dramatic rise-and-fall story of a celebrated Mob boss who became one of the world's richest men, a Robin Hood who gave to the poor, a modern-day Houdini who escaped from not one but two maximum-security prisons.

And it was great show business with a full cast of characters: a compelling antihero, high-level drug traffickers who "flipped," a sexy mistress, a beautiful young wife in the gallery.

It had titillating stories of luxury jets, private zoos, a naked escape (with said mistress) through an elaborate tunnel, and wretched excesses of wealth that would bring a blush to the faces of the most shameless "stars" of reality TV.

There was even a hint of celebrity, as the actor who portrays the defendant in the Netflix drama Narcos: Mexico made the pilgrimage to see his real-life inspiration.

Yes, Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman Loera, the infamous jefe of the all-powerful Sinaloa cartel—"the godfather of the drug world," as one D.E.A. official styled him—was brought to justice in a trial meant to stand as a major victory in the war on drugs.

No fewer than 56 prosecution witnesses gave detailed, sometimes tedious, often gruesome testimony about beatings, tortures, and murders. (There was even a suggestion that the jurors might be vulnerable to P.T.S.D., which seemed a tad overwrought.) The defense case was mercifully brief—one witness. Guzman, on the advice of his lawyers, chose not to testify in his own defense. It was good advice—the prosecutors would have ripped him to shreds on cross-examination and he would hardly have made a sympathetic witness—but disappointing in that it deprived us of one crucial dramatic beat in any celebrity trial. In an ideal show-business world, Guzman would have taken the stand and delivered a money line: "You want answers? You can't handle the truth!" (More on that below.)

The jurors took their time—six days—deliberating, causing some anxiety for the prosecutors and even some breathless media speculation that he might get off. All attorneys know that any time you send a case to a jury, you are rolling the dice. Despite your best attempts in voir dire, you never know what baggage an individual juror might bring in with him or her—a grudge against the legal system, sympathy for a charismatic rebel, a tent pitched firmly on a grassy knoll, a hang-'em-high mentality successfully concealed until it emerges full-blown in the jury room. Anything can happen.

And the jurors faced a difficult task: to weigh guilt or innocence on 10 complicated charges including conspiracy to traffic drugs, conspiracy to commit murder, and complicity in running an international criminal organization. Conviction on any one of the counts would send the defendant to prison for the rest of his life.

The jury found Guzman guilty on all counts.

It was the right call—the evidence was overwhelming.

The U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of New York called the verdict a victory for law enforcement, for Mexico, and for the families who had lost loved ones to drug addiction.

All that is true.

And yet, in the big picture ...

None of it mattered.

The Guzman trial will do nothing to stem the flow of narcotics into the United States.

Don't get me wrong. Convicting Guzman for trafficking literally tons of drugs into the U.S. was a good thing. He's not Robin Hood. He's a killer responsible for untold suffering—surely far more than he's charged with—and if he spends the rest of his life in prison it will be something like justice.

But his capture and prosecution do nothing to ameliorate the American drug problem, and his conviction is likewise meaningless.

The reason is simple.

By the time of Guzman's capture, "escape," and recapture in the farce that made him a celebrity, he had already lost most of his power.

He was superfluous.

Expendable.

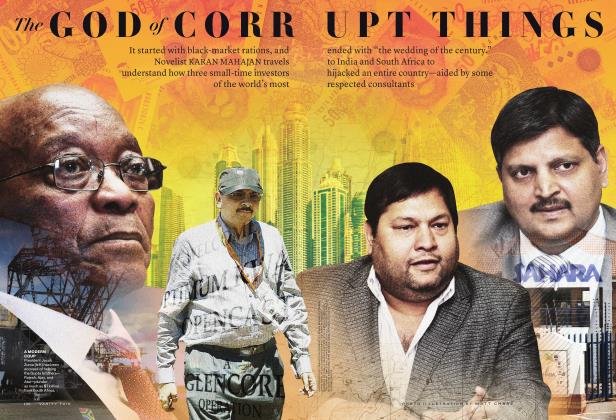

The critical thing to understand is that Guzman wasn't—and never would be—the sole "boss" of the Sinaloa cartel. We tend to think of cartels as pyramids, with a single head at the top, but in fact they're more like wedding cakes with several tiers.

Guzman was on the top tier, with others, the most important being Juan Esparragoza Moreno (widely rumored to be deceased), the late Ignacio Coronel Villarreal, and a man named Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada, who has been prominently featured, albeit in absentia, in this trial.

A time-tested defense-attorney maxim says that, if your client is obviously guilty, put someone else on trial. In their opening statement, Guzman's lawyers argued that he wasn't the real boss of the Sinaloa cartel, long the biggest drug-trafficking organization in the world. Instead, they claimed, that honor belonged to Zambada, and he has paid hundreds of millions of dollars in bribes to high-ranking officials in the Mexican government in order to remain, well, in absentia.

Witnesses, including Zambada's own brother and son, testified to the same.

But nobody calls Mayo Zambada the "godfather of the drug world," and that's the way he likes it. You don't see Zambada interviewed in Rolling Stone, trying to launch romances with television stars, or working on a biopic about himself, as Guzman did.

Zambada is a conservative businessman who prefers to stay behind the curtain. (If there is a Don Corleone of Mexican drug lords, it is Ismael Zambada.) And his partner Guzman was becoming increasingly problematic.

Mob bosses remain in power as long as they're making other people money. Guzman had begun to cost people money. At the start of his downfall, he was suffering huge declines in marijuana profits due to legalization in America. Everyone was, and one of the cartel's responses was to get back into the heroin market for the first time since the 1970s, in order to grab a cut of the American pharmaceutical companies' booming opioid-addict market. The cartels produced so much heroin that they created a surplus, which, in a reversal of previous policy, they started to sell inside Mexico.

Guzman got greedy and demanded a cut of the profits from local dealers in Sinaloa, thereby alienating his own power base. Combine that with his increasingly bizarre antics—more about that later—and it's clear why he had become a liability to his partners, principally Zambada. Sources in Mexico inform me that Zambada— aging and ailing—has been wanting to take his billions and retire quietly.

The real drug godfathers sit in offices, not in a trial dock or a cell.

But he had another problem besides Guzman: two sons who were facing long sentences in the United States.

In 2010, Zambada's son Vicente was extradited to the U.S. for drug trafficking and was looking at a potential life sentence. In November 2013, his brother Serafin was arrested in Arizona for conspiracy to traffic cocaine and methamphetamine and faced a sentence of 10 years to life as well as a $10 million fine.

In 2014, it came to light that Vicente had cut a secret plea deal agreeing to testify against Guzman. In February 2015, Serafin was transferred to an undisclosed location, but there was no record of him in federal custody. It was widely assumed at the time that he, like his brother, needed someone to "trade up" for, and that it wasn't going to be his father. The increasingly erratic, increasingly public Guzman was the obvious candidate. It is no coincidence that Guzman was initially captured while the Zambada brothers were making their deals.

In March 2018, Serafin was sentenced to five and a half years. He was released last September.

Still, Guzman retained enough support, influence, and money to engineer his 2015 "daring escape," allegedly accomplished through a near mile-long tunnel dug under the maximum-security-prison walls and also under the supposedly unwitting noses of the Mexican Army, the federales, and the prison authorities.

It was neither daring nor an escape, but rather a bought-and-paid-for departure. Prison surveillance video shows a fully dressed Guzman "getting into the shower" behind the privacy wall (enough said) in his cell, which blocks the view as he supposedly goes down the tunnel entrance. Despite the testimony of Guzman's former right-hand man, Damaso Lopez, there is still cause to doubt that he ever went into that tunnel. If you can afford $15 million in construction costs and bribes to build a tunnel, you can also afford not to have to use it. It's possible he went out the front door, the same as he did during his first "escape," in 2001, for which there was also a face-saving official explanation—that he went out hidden in a laundry cart.

Guzman might actually have remained free if this spectacle hadn't brought so much attention and embarrassment to the Mexican government. The media frenzy brought pressure, especially from the U.S., that forced Mexico to launch an intense manhunt as well as raids, arrests, and seizures of product targeting the whole Sinaloa organization.

In other words, Guzman's shenanigans cost the cartel money.

The old truism that there's no such thing as bad publicity is definitely not true for organized-crime figures, and for whatever reason—whether he became enamored of his own press clippings or just came to believe his own legend—Guzman started to seek the limelight. He wanted Hollywood to make a biopic about him and that effort—combined with his infatuation with Mexican soap-opera star Kate del Castillo—led Guzman to sit for an infamous interview with the actor Sean Penn for Rolling Stone magazine.

The export of cocaine, meth, and heroin didn't even slow after his arrest.

The article, which disclosed that Penn and del Castillo passed through a nearby army checkpoint on their way to the meeting, has been credited with leading Mexican law enforcement to Guzman's location. Let's be real. They already knew where he was. But the publicity helped persuade Zambada and other decision-makers that it was time not just to allow Guzman to be removed but to demand it. The only condition was that he not be hurt.

Five of his associates were killed in the raid that netted him, but Guzman and his assistant were unharmed.

This much is sure: Guzman would not have been recaptured or extradited without the permission and cooperation of Zambada and other powerful figures in the cartel and Mexican government.

Now Vicente is seeking the rare and coveted S-5 visa, which will allow him and his family to remain in the U.S. for three years—and indefinitely, if all goes according to plan. His testimony at the trial included a lot of incriminating evidence about Guzman, as well as about his own father, whom he named as the head of the Sinaloa cartel. The testimony that Vicente did give has been viewed as a betrayal of the cartel and his father, but was it really? Or did the father give his son permission to save himself by telling what everyone already knows anyway, a common practice among narcos facing long sentences in the U.S.? Unlike the Mafia, the Mexican cartels encourage their members who have been arrested to tell everything they know if they can cut a deal for a shorter sentence—all they are obliged to do is relay what they've given up to defense attorneys, who then pass the information on so the cartels can make the necessary adjustments.

And the most damaging testimony Vicente has given has been against Guzman. In a sense, one can view the Zambadas' testimony as an extension of the internal conflict now being fought between the "Zambada faction" of the Sinaloa cartel and the "Guzman faction," led by three of Chapo's adult sons.

The fix was in, and that's why this trial made no difference to the overall drug problem. The export of cocaine, methamphetamine, and especially heroin didn't even slow after Guzman's arrest.

To be sure, the cartel has been in chaos since Guzman's extradition, but it is partly due to internal bickering, because the power-sharing arrangement that Guzman had envisioned among his sons, Zambada, and Damaso Lopez has fallen apart.

The larger issue is the rise of a new powerhouse: the Jalisco New Generation cartel, which is successfully contesting the Sinaloans for smuggling routes, border crossings, and poppy fields. Other, smaller organizations have also rushed to fill the power gap. Perhaps as a result, in the wake of Chapo's extradition, Mexico has suffered its two most murderous years since its government started to keep track, in 1997.

If you think that Guzman's incarceration has been a major victory in the war on drugs, explain why heroin overdoses in the United States have risen dramatically, not fallen, since his capture.

The drug problem has gotten worse, not better.

It's business as usual, because it's set up to be.

Guzman was one piece, albeit an important one, in a complex machinery composed of drug traffickers and police (on both sides of the border), as well as military, judicial, political, governmental, and business entities. Together, they make the international drug trade possible.

The scope of this enterprise is gargantuan.

We're talking about hundreds of billions of dollars a year that flow from the United States to Mexico, money that has been re-invested in legitimate businesses in Mexico, the United States, and around the world.

Some of it finds its way into the pockets of top government officials— including one or more presidents, if Guzman's lawyers and some witnesses are to be believed.

Mayo Zambada's brother, Jesus, now in prison in the United States, testified that the partners in the cartel pooled more than $50 million to bribe the government of then president Felipe Calderon (this accusation is strenuously denied). He has further stated—although Judge Brian Cogan suppressed this testimony— that he paid several million dollars in bribes to a representative of current president and then Mexico City mayor Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador. (Lopez Obrador has declined to comment on this allegation.)

Alex Cifuentes, a former high-ranking Guzman aide, testified that the cartel sent $100 million to then Mexican president-elect Enrique Pena Nieto (2012-18) to protect Guzman from capture, and that he told American authorities about the alleged bribe back in 2016. Spokesmen for Pena Nieto have indignantly denied Cifuentes's claim.

We might well suspect the veracity of drug traffickers. They are certainly not angels, and mendacity would be the most venial of their sins. But there are good reasons to believe them: They are all in American federal custody and have negotiated lenient sentencing deals that would be voided if they were found to have committed perjury. As such, they've already pleaded guilty to drug charges and therefore have nothing to hide. Furthermore, they haven't contradicted one another, and audio-surveillance tapes entered into evidence have confirmed important parts of their testimony.

Most importantly, the "revelations" that these witnesses brought forward aren't revelatory—they merely confirm what we've always known. I've been writing about the Mexican drug world for two decades, and I've heard credible accounts of these bribes and payoffs continually from day one. I'm not unique in this regard—one highly respected journalist after another has reported these stories, some at the cost of their lives.

The point is that systemic corruption has been in place for many years, it remains in place, and it is far larger and far more powerful than a single defendant, even the supposed "godfather of the drug world."

The real godfathers of the drug world sit in comfortable offices, not in a trial dock or a cell.

Sure, putting away a bad guy like Guzman is a good thing. But he's only the latest in a long list: Pedro Aviles; Miguel Angel Felix Gallardo; Amado Carrillo Fuentes, the "Lord of the Skies"; Pablo Escobar; Nicky Barnes; Benjamin Arellano Felix; Osiel Cardenas; and now Chapo Guzman.

To what end?

Drugs are more plentiful, more potent, and less expensive than ever.

We'll never find an answer to the drug problem until we ask the big questions about systemic corruption; the nexus between drug trafficking, government, and business; the prison-industrial complex that is funded by drug convictions; and the very nature of drug use and addiction itself.

What is the true nature of the drug-trafficking machine? What is the depth and width of the corruption that allows it to flourish? Where do the billions of dollars go? How does it provide protection, and who provides that protection?

And something else. And maybe this is the truth that we can't handle.

Corruption is not the sole property of traffickers and their enablers.

We own it, too. We have to ask the question: What is the corruption of the American soul that makes us want the drugs in the first place? Opioids—which are killing more Americans now than either car crashes or guns—are a response to pain. We have to ask the question: What is the pain?

Until we ask and answer that question, the drug problem will always be with us.

And the trial of the century?

Sorry, but it just doesn't matter.

Don Winslow is the best-selling author of The Cartel, The Power of the Dog, and The Border.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now