Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCZECHED OUT

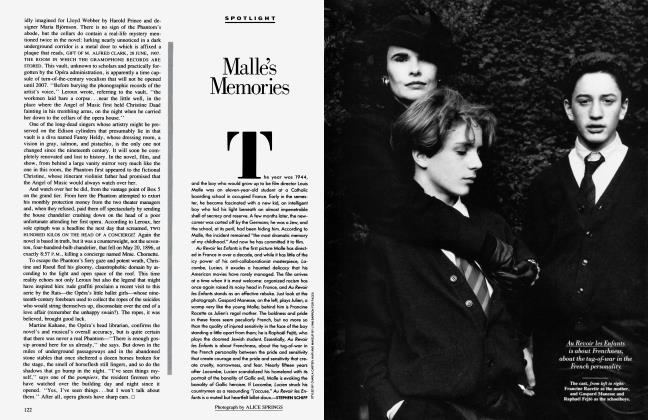

STEPHEN SCHIFF

What happens when an Eastern European novel (The Unbearable Lightness of Being) gets trapped in an American movie?

Movies

If satire is what closes on Saturday night, literary adaptations are what open in the dead of winter. Since December, we've already had Ironweed (from William Kennedy's novel), Empire of the Sun (from J. G. Ballard's), The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne (from Brian Moore's), and The Dead (from James Joyce's short story), all high-minded, lovingly wrought, imbued with respect for the Printed Word—and, except for The Dead, all utterly mediocre. And now perhaps the most challenging of them all, Philip Kaufman's three-hour movie version of Milan Kundera's novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Which turns out to be absorbing and thoughtful, even painstaking. And also strangely lifeless.

The truth is, adaptation rarely works. In the studio days (and long after), it was the province of Hollywood's crudest vulgarians, who would toss plots and characters around like so much salad in order to whip intransigent "classics" into box-office fodder. Nowadays the problem is almost the opposite: adaptations are likely to be vitiated by a kind of hysterical reverence, by moviemakers who strain to commit the unfilmable to film—faithfully. Why do they do it? Why not just let books be books? In the first place, because Hollywood is hungry, and good original screenplays are rare. And then because, like the rest of us, moviemakers often find they can't get a book and its characters out of their head, can't stop mentally casting and scouting locations. And also, sometimes, Because It's There.

Unfortunately, the best books, the ones moviemakers tumble for, are generally the ones that burrow deepest into their characters' psyches. And film isn't always good at burrowing. The medium is attuned to surfaces, to what can be gleaned from the outsides of things. In a more innocent era, the gap between outside and inside was bridged by lots of talk. But in the age of rock videos and Stallone movies and 501-jeans commercials, words on-screen have become faintly embarrassing. Narration feels comball; naked emotional declarations sound as mawkish when we watch them as they do when we catch ourselves making them.

The movie version of The Unbearable Lightness of Being won't be remembered for catchy lines—if anything, it may be remembered as yet another valiant attempt to film the unfilmable. It manages, for instance, to turn Kundera's spiraling structure, which tells the same story a2ain and again from different points of view, into a coherent and pleasing linear plot. We watch Tomas (Daniel DayLewis), a brilliant but wildly promiscuous neurosurgeon, fall in love with an unsophisticated provincial girl, a photographer named Tereza (Juliette Binoche), and, much to everyone's surprise, marry her—which doesn't, however, dent his philandering. The setting is Prague, in 1968, the year of Dubcek's reforms, of "socialism with a human face," of unprecedented freedoms and artistic efflorescence, and finally of the Soviet invasion that overnight transformed Czechoslovakia into one of the most repressed nations in Europe. Tomas and Tereza flee to Switzerland, but though Tomas flourishes there—with plenty of women, including his favorite Prague mistress, Sabina (Lena Olin)— Tereza pines. Impulsively, she returns to Prague, leaving Tomas a note: "I can't bear this lightness, this freedom. ... I'm weak and I'm going back to the country of the weak." And Tomas finds he can't bear lightness and freedom either, not without her. Fatefully, irrationally, he, too, returns to Czechoslovakia— where life is now plenty Heavy.

The film is clearly a labor of love—and worship. But Kaufman (who gave us The Right Stuff and the second Invasion of the Body Snatchers) has made the mistake so many latter-day adapters make. He's all but submerged his own exuberant sensibility, the better to accommodate what he takes to be Kundera's— stem, ravaged, intellectual, deep. The result is a real oddity: an American epic with the icebox aroma of an Eastern European art film. The spooky, plangent music is by Leos Janacek, and Ingmar Bergman's superb cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, has shot the film in filtered colors that make the light itself seem as if it were struggling against some unseen repression. But the (Continued from page 40) movie never connects that sensation with the characters—they don't look repressed, they look confused. "What concerned me," the coscreenwriter, Jean-Claude Carriere, has said, "was getting across on the screen the love story between a libertine and a faithful and jealous woman... that mysterious love between Tomas and Tereza." And that's just what's missing. Kundera captures it in the novel by dissecting their passion the way a Talmudic scholar dissects a parable. But the filmmakers can't burrow in that far, and no wonder: to get into Tomas's and Tereza's heads, they first have to explore Kundera's.

Continued on page 49

Continued from page 40

Which is not at all like burrowing deep inside Mario Puzo. For all the seductiveness of his lite-FM prose, Kundera is reminiscent less of other novelists than of a physicist conducting thought experiments. His characters are overtly figments, dolls set dancing like so many magnetized particles between their creator's favorite polarities—lightness and weight, body and soul, art and kitsch, East and West. Kundera approaches characters not through what they do and say but through the little essays he can write about them, and any moviemaker who thinks it's tough to capture a fictional character's internal stirrings ought to try capturing an author's; the screenplay throws out oblique references to kitsch and the Grand March and other Kunderiana, but most of the time it just flounders. Worse, Kaufman and Carriere seem to be striving to make up in weighty tone for what they lack in weighty substance. Kaufman's customary elan is gone, and with it his sense of narrative rhythm; the movie feels muffled, chastened, wan. You can almost hear the filmmakers assuring us, "Kundera would have wanted it that way."

It ut I doubt it. When Kundera talks K about the unbearable lightness of beftr ing, he's not condemning lightness, he's simply exploring a paradox. Lightness, the absence of burdens and fetters and ties, is marvelous, he's saying, but it also makes everything one does seem trivial, dismissible; and weight, which is onerous and binding, nevertheless makes one's activities feel significant, earthbound, real. In Kundera's terms, America has always been blissfully light—light in ways its artists have often found hard to live with. The trouble with Kaufman's Unbearable Lightness of Being—the reason it feels not only sluggish but false—is that in tackling the woes of Eastern Europe the filmmakers are trying, out of a kind of misplaced piety, to mimic Eastern European heaviness. Yet what makes Kundera's novels work is not their weight but their ironic lightness—or, rather, the magisterial balance he finds between the two.

At moments, Kaufman finds it, too. The movie's sex scenes sail along, for instance, mostly because sex in Eastern European movies is usually pallid and pimply, and Kaufman's all-American boldness—he's fond of mirrors, muscles, and crotch shots—throws off sparks. During the early parts of the film, he eroticizes Tomas's every move, and Day-Lewis performs as if his hormones were on fire, smirking and leering, slinking through the dank hotel and hospital corridors on little cat feet, sniffing at Sabina like a famished satyr. And though Day-Lewis (who was so powerful in My Beautiful Laundrette) sometimes has trouble opening up to the camera here, his two co-stars do not. The French actress Juliette Binoche projects a quirky lyricism, a mix of childish awkwardness and equally childish sensuality. And the Swedish actress Lena Olin is a knockout, with a knowing, grown-up eroticism that threatens to scorch the other actors off the screen.

If aufman has managed another small II wonder: in the middle of the film, he's II secreted a cinematic jewel. He and Nykvist and their editor, Walter Murch, have compiled newsreel footage of the Soviet invasion and matched it perfectly with shots of Tomas and Tereza marching, protesting, taking verboten photos amid the tanks and troop trucks. And though this sort of thing has been tried before, no one has ever brought it off with such technical panache, with such an understanding of the way we experience news on film. The moviemakers have cleared enough space at the movie's center to give their tour de force extraordinary weight, and yet Kaufman's style here is light, brisk, and confident, the way it was during the space-footage scenes of The Right Stuff. The effect is to kick the characters alive, to push them out of their La Boheme garrets—out of fiction—and into the noisy parade of history. Watching it, viewers who know those 501-jeans commercials by heart may understand, perhaps for the first time, the way Eastern Europe's public catastrophes have crushed private lives, lives not so different from their own—and they'll understand it as deeply as Kundera's readers understand it. That's the way adaptation ought to work: not by translating the matter of a book, Classic Comics-style, but by reinventing it from the ground up—as film.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now