Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLust Cause

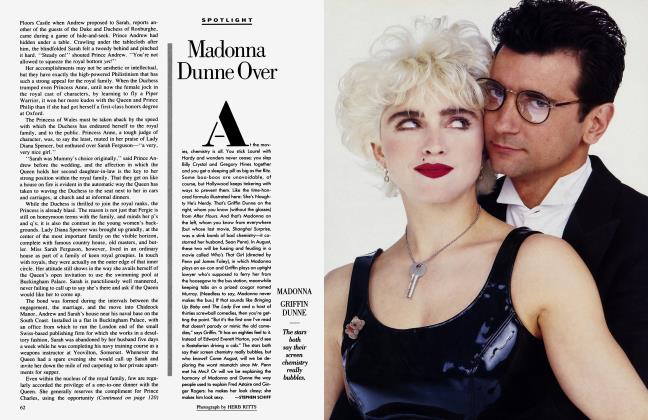

The brave new boudoir of 9 1/2 Weeks

MOVIES

Sex has been the great missing movie subject for so long that it’s become shocking again. Even when it’s served up slick from the deep-fat fryer, as it is in 9Vi Weeks, it feels subversive, urgent—serious. In this junkfood Last Tango, sex isn’t cuddly fun, the way it is in the teen comedies and domestic melodramas of the last few years. It’s scary. And the scarier it gets the better it feels.

The movie comes from a memoir by Elizabeth McNeill, a pseudonymous New York journalist who spent nine and a half weeks making crazy sadomasochistic love with her well-heeled paramour and then, rounding the bend toward week ten, careened into the breakdown lane. The book is a fairly creepy read, but Adrian Lyne—who directed Flashdance—has “opened out” the claustrophobic story and let it breathe (or pant). Elizabeth (Kim Basinger) is now a S0H0 art dealer who falls for a burr-voiced arbitrage whiz named John (Mickey Rourke), and their affair is no longer S&M, it’s something more eclectic—domination, dress-up games, and, of course, flashdancing. 9'h Weeks is kinky, but it never slops all the way over into sicko. It doesn’t have to; Lyne makes the boundaries between Elizabeth’s humdrum days and her steamy nights feel dangerously filmy and porous. Without getting terribly explicit, he has created the most sexualized relationship we’ve seen in years.

With her Bardot pout and her sullen, slightly puffy voluptuousness, Kim Basinger at first seems bom to be calendar art. But when Lyne tries to use her that way, as a simple sexpot, the movie looks whory and cheap. In fact, Basinger’s Elizabeth is the movie’s subject, not its object; she’s the quivering sensibility the audience identifies with. And Basinger

pulls it off. You can feel her inflamed nerve endings burning tiny holes through her skin—she’s appetite personified.

Next to her, Mickey Rourke’s John is a cipher. Nothing he does is meant to express character; it’s all calculated to crank up the sexual electricity. When he and Elizabeth go to lunch in a crowded Wall Street bar, there’s no civilized discourse, no pleasure in ordinary companionship. These two would rather grope and nudge and play gooey games with their drinks. For Lyne, passion is a drug that turns the everyday world into a charged-up dream. His characters shun the mundane, or transform it—everything becomes eroticized. A car whooshes by and splashes Elizabeth. Maddening? No; the sludgy water makes her tingle. John forces her onto a Ferris wheel and stops her car at the top.

Fun? No, scary—no, fun. Elizabeth dresses up as a man, and she and John are (improbably) chased in the rain by knife-wielding gay bashers. Frightening?

No, thrilling; after trouncing the marauders, the lovers can’t wait to jump each other’s bones—right there in the street, amid the rank splash of flushing gutter pipes.

Lyne’s hyped-up direction and Peter Biziou’s airbrush camera turn the world into a giant rock video, but they also make every surface, every color seem ambiguous, questionable. And the question is always the same: Is this pain or pleasure? What distinguishes one from the other? In the film’s soggiest subplot, a morose painter gasses on about “the moment a thing is so familiar that it’s strange” (these words intoned while ostentatiously examining a fish). In its own glitzy way, 9V2 Weeks is about film itself: caressing the skin of things, Lyne’s camera can make the familiar look strange, can make the comforting terrify, can make a fish or a murder or a wound appear either disgusting or sumptuous. That’s why Rourke’s icy performance—the rosebud smirk, the mocking and distant eyes—seems so in-

sinuating. As long as he is a figure without a past, stripped of emotions and vulnerabilities—pure surface—Elizabeth can feel about him whatever she wishes. He’s a fantasy object, a wild ride: something far less demanding than a man.

9V2 Weeks is dopey enough to bury its own subtleties in schlock; during its feckless art-gallery scenes and fleshpots-ofTimes Square scenes, you could swear you were watching 120 Days of Sodom Starring the Solid Gold Dancers. And Lyne’s visual ooh-la-la obscures not only what’s interesting in the picture but also what’s ominous. Like Flashdance, this movie is geared to a society obsessed with aspiration: if the earlier film was about career ambitions, the new one is about bedroom ambitions. 9V2 Weeks is a love story for coffee achievers, one in which the gleaming yups who spend their days going for the big deal spend their nights puffing toward the big orgasm. It’s vital to the movie’s allure that John’s apartment be a slate-gray altar to minimalist chic, that all the furniture, from the leathery Breuer chairs to the looming banks of video, look like high-tech tools, like Nautilus machines. And it’s vital that we accompany Elizabeth as she rummages through John’s closets: the rows of identical superbly fitted suits, the piles of identical superbly laundered shirts. John’s world bespeaks a kind of exalted discipline—very Teutonic and martial, very Triumph of the Will. If you become a slave to the Quotron or a slave to your lover, with his blindfolds and his imperious commands, you will make yourself greater; you will outstrip your puny, indulgent former self. In Lyne’s vision de Sade meets Nietzsche, and it’s a duet made in heaven—“Whatever doesn’t kill me makes me stronger,” they croon. Which is not exactly music to my ears. I’m grateful to Lyne for restoring sex to the cinema—but his lip-smacking dream of the brave new boudoir gives me the willies.

Stephen Schiff

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now