Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFor years, State Department official Matthew Gebert's white nationalism was a secret. Then, he was outed.

April 2020 Peter SavodnikFor years, State Department official Matthew Gebert's white nationalism was a secret. Then, he was outed.

April 2020 Peter SavodnikIT PROBABLY STARTED with an ex-cop— they're usually ex-cops—asking him questions about extramarital affairs, credit card debt, aliases, weekend getaways to ex-Soviet backwaters— anything that could have been used against him. The ex-cop probably didn't know a lot about the job Matthew Gebert was applying for, the officials Gebert would brief, the top secret information Gebert would have access to. Nor was he a reader of souls. His job was simply to ascertain whether the answers on the standard form, or SF-86, that Gebert had filled out were true. Whatever his background, he was a part-time employee of a contractor hired by the Department of State's Bureau of Diplomatic Security to process security clearances. He was probably padding his pension. It was probably this or Uber.

Diplomatic Security signed off. Gebert was smart. He had recently been awarded a presidential management fellowship, according to an alumni news update in GW Magazine—he was a future leader.

Months elapsed. One day, an email arrived in his inbox: Gebert had been offered a job at the State Department's Bureau of Energy Resources. He became a civil service officer. He reported to important people—deputy secretaries, political appointees—and these people reported to really important people. He attended meetings about the economic sanctions imposed on Iran and international oil flows and making sure the Russians or Indians don't "fuck us," as one former diplomat put it. His job, like those of his colleagues, was to advance the national interest.

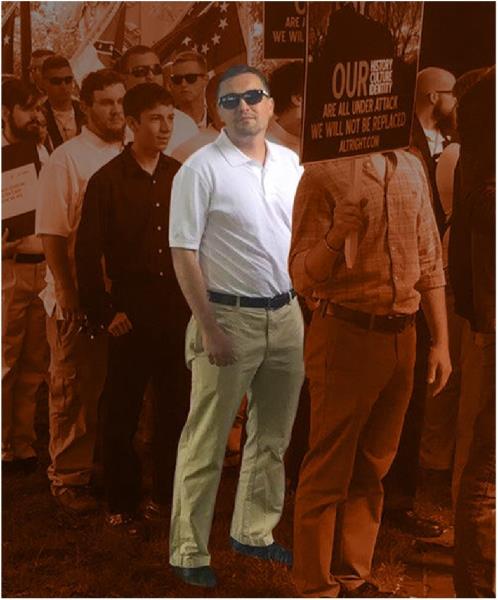

Matthew Gebert wore sunglasses to the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Matthew Gebert wore sunglasses to the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.

It was 2013. Gebert's life was practically a caricature of a life people used to live. He was in his early 30s. He and his wife, Anna Gebert, nee Vuckovic—blonde, of Serbian extraction—owned a five-bedroom, three-and-a-half-bath neocolonial at the end of a cul-de-sac in a planned community called Greenway Farms, in the sprawling epicenter of planned communities that was Northern Virginia. Government contractors, engineers, ex-military. Stepford-ish. He had a baby, then two more. His patch of lawn was always mowed.

His kids made friends with other kids, rode bikes, attended a nearby school. When his son Alex was born, at Inova Loudoun Hospital, the Stanley Cup happened to be in the house—a Washington Capitals coach lived in the neighborhood—and for 90 minutes the three-foot-tall, 34-pound silver chalice made the rounds, local media reported at the time. Gebert asked if he could put Alex in there for a pic, and with a nod from the coach, his son, who was literally one day old, was napping in the Stanley Cup. American Dream: realized.

At Foggy Bottom, at Greenway Farms, he was just Matthew Q. Gebert. "Boring dad government dude," one of his colleagues said. People described him as friendly, straitlaced. He wasn't one to socialize outside of normal work hours, according to colleagues. He usually left early—he had an hour-and-a-half commute home. But that was only half of Gebert. The other half was a secret, and for several years it stayed that way.

TWO YEARS INTO his job at the State Department, Gebert started dabbling in the alt-right—the loosely knit constellation of white nationalists and white supremacists who constitute some of the president's fringiest supporters. Eventually, he became a fixture in the alt-right scene, reportedly running a local chapter called the D.C. Helicopter Pilots, according to Southern Poverty Law Center blog Hatewatch, in an apparent allusion to the late Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, whose supporters were known to throw political opponents out of helicopters. In those circles, Gebert was known mostly as Coach Finstock. (It was an odd pseudonym. Coach Finstock was a character on the MTV series Teen Wolf, and he was played by Orny Adams, a Jewish comedian.) Among his acolytes, he was just Coach.

He mostly played the role of den father for 20-something latchkey haters. The former alt-right provocateur Katie McHugh, who last year publicly denounced the movement, is said to have crashed at the Geberts' house for several weeks. (McHugh did not respond to a request for comment.) Anna Gebert served on the board of a local tourism association, Visit Loudoun, while complaining privately that Loudoun County was becoming too diverse, according to a Washington Post column. The couple reportedly served swastika cookies to like-minded guests.

Gebert's evolution happened slowly, and then all at once. He grew up in the Democratic stronghold of Stratford, New Jersey. Race didn't appear to be a big deal—at least not openly. There was some gang violence, but heroin was a bigger problem, according to a source. Gebert was a standout. He read, traveled to Ukraine and Russia, and studied in Moscow through a program at American University; he acquired an affection for all things Slavic; he met his wife, who was studying abroad through Northwestern University, according to Hatewatch.

In 2015, Gebert escaped the "conservative reservation," as he reportedly put it. In a 2018 appearance on a podcast hosted by alt-right figure Ricky Vaughn, speaking as Coach Finstock, he traced his shift to the immigration bill cosponsored by John McCain and Ted Kennedy. "That was sort of what got my wheels turning was McCain, Kennedy in 2006, when they were trying to do that amnesty, as I saw MS-13 proliferating throughout Virginia." In 2015,2016, everything started to coalesce, both online and off: Donald Trump, the wall, the obvious passions and furies the Republican nominee was tapping into, the fecklessness and hypocrisy of GOP "leadership."

In alt-right parlance, Gebert was red-pilled. Alt-righters may present better than run-of-the-mill bigots, but their beliefs are hardly sophisticated; they subscribe to the same anti-Semitic mythologies that have been coursing through the ether for centuries. But because they read newspapers and have a glancing familiarity with big ideas, they sound credible to those on the precipice—those in search of an identity. Gebert is believed to have socialized with leading alt-right figures like Richard Spencer and Michael Peinovich. Spencer, in 2016 and 2017, was best known as the face of the movement. Peinovich, who goes by the name Michael Enoch, founded the alt-right blog and podcast network the Right Stuff. (Peinovich, in a rambling telephone conversation, denied having heard of Gebert, despite reports of Gebert hosting Peinovich at his home.) Gebert, like Spencer and Peinovich, was in Charlottesville in August 2017, for the Unite the Right rally that left one protester dead, his brother Michael Gebert told Hatewatch. In 2018, he reportedly donated $225 to the Republican congressional candidate Paul Nehlen, best known for his anti-Semitism.

According to a complaint of discrimination one of Gebert's colleagues filed against him with the State Department's Office of Civil Rights, Gebert debated the pros and cons of Charlottesville in an online post just after the rally: "Dude, we smacked the hornet's nest with a big fucking stick.... [T]he only question is whether this is valuable accelerationism or whether we just provoked the red guards, like, a year before we had enough time to spare." The complaint also cites one of Gebert's now deleted tweets, posted under his Coach Finstock alias, which featured a photograph of Nazi soldiers forming a massive swastika while carrying torches, with the caption: "It's that time...again." (Sources told me the complaint was dismissed, largely on First Amendment grounds.)

Several months before Gebert tweeted the swastika photograph, he appeared on Vaughn's podcast to, in his words, "defend the movement, to defend my friends." (Vaughn, whose given name is Douglass Mackey, has come under attack from fellow alt-righters for not being adequately alt-right. Not long after the podcast aired, Nehlen, the Republican congressional candidate, doxed him, sending Vaughn's life into a tailspin.) Gebert was angry with Vaughn for sowing discord among the movement. He said, more than once, that it was important to "name the Jew," alt-right speak for using openly anti-Semitic terms. Vaughn said Ann Coulter and Tucker Carlson were susceptible to "Zionist propaganda," which Gebert appeared to agree with, but then Gebert said, "The service that Tucker is doing on Fox News is unquestionably of value to the boomers sitting in their La-Z-Boys and watching it every night and dropping those bombs."

At one point in the conversation, Gebert turned somber. He was discussing his double life. "I take these risks because I have a grave sense of foreboding that this country and all of the white countries on earth are on a collision course with perdition, with disaster," he said. "The only reason I'm taking this risk is so that my kids can grow up in a whiter country."

In 2018, Gebert's security clearance— a Top Secret, Sensitive Compartmented Information clearance, which gave him access to an array of highly sensitive intelligence across the U.S. government—was renewed. "None of these interviewers ever, I would say, was an impressive human being, but this was truly unbelievable," one of Gebert's former colleagues said. Another former colleague added, "How could you not connect the dots?"

I attempted many times to reach out to Gebert for comment, first through email, then through a phone number I believed to be his, then through his family members, none of whom replied. I tried knocking on his door and leaving my contact information with a neighbor, all to no avail.

FOR YEARS GEBERT took a combination of trains and buses into D.C., went to work, came home, logged on. He and his wife were model neighbors. They could be relied on, in a pinch, for sugar or milk. ("I've had Nazi milk," one neighbor said. "Jesus, to think of that.") They adhered to the homeowners' association bylaws and painted their house one of the colors in the Duron Curb Appeal-approved exterior accent palette—in this case, wheat, or maybe amber white, with forest green trim. None of the neighbors I spoke to disliked him.

Then, on the morning of August 7, 2019, Hatewatch reported that Gebert was the leader of an alt-right cell in Northern Virginia, and that he had posted anti-Semitic comments on white nationalist forums and been a guest on a now defunct podcast called The Fatherland, which addressed issues like white demographic decline and "the subversiveness of girl power."

Within minutes, "the story was being read on most of the screens in the building," a State Department employee said. It didn't take long for the story to start ping-ponging around the globe, from one U.S. embassy to another. As far as the higher-ups at State were concerned, there were two big problems with Gebert being a civil service officer. The first was that his unmasking had made him repugnant and toxic. The second was Russia. Multiple State Department sources suggested that Gebert's apparent affinity for Slavic culture, particularly as related to his white nationalist leanings, would be considered problematic.

He was—no surprise—against the Iran sanctions, in large part, former colleagues speculated, because Russia was too. "He worked with people involved in the Iran sanctions," said Alex Kahl, who worked with Gebert at the Bureau of Energy Resources. "When you do these negotiations and you have large teams, you have to use the same email LISTSERV, and that goes on the top secret system. He would have been watching the whole strategy discussion. Remember, our goal was reducing Iranian crude oil exports—removing those barrels from the market but maintaining market stability. Matt was privy to all these discussions."

"We engaged the buyers of Iranian crude oil and worked with them to reduce demand," Kahl said. "So Matt would have understood, for example, Indian purchases of Iranian crude oil. We look at this as a whole ecosystem, so we make sure that everybody knows what everybody else is doingconnecting dots.... He had access to all that information." That, Kahl said, is concerning. "Anyone who's a white nationalist is not an American patriot."

Amos Hochstein, who was appointed deputy assistant secretary of state by Barack Obama in 2011 and oversaw the Bureau of Energy Resources for part of the time Gebert was there, could recall being in many meetings with Gebert. "I think that Gebert is a symptom, and he's a warning sign because he got careless," said Hochstein, who is an Orthodox Jew. "The idea that there's only one white nationalist neo-Nazi rising in the ranks of the national-security establishment is difficult to imagine." He said that Gebert had been polite, capable. He said he had tried to help him professionally, because that was good for Gebert and for America. "I shook his hand on—I have no idea how many times. His shoulder rubbed up against mine, when we were in meetings, you know, when you're next to someone. I think about that a lot."

About an hour after the Hatewatch story went live, Gebert emailed two of his superiors about what he characterized as a hit piece, according to a source, and said he was leaving for the day. Soon after, his name was scrubbed from State's phone directory. Investigations—at State, at the FBI, and on Capitol Hill—were launched. He is believed to be on unpaid leave. According to a source, he has not been on payroll since at least October.

"The IDEA that there's only one white nationalist RISING IN THE RANKS of the national-security establishment is DIFFICULT to imagine."

AS THE FALLOUT from the story reverberated, there was a sense among the alt-right that Gebert had been sloppy, and maybe, naive. Greg Johnson, the editor of white nationalist publishing house Counter-Currents— which both Matthew and Anna Gebert, under their respective aliases, had written for and which is based in San Francisco—said in an email that Gebert was "an intelligent, educated, racially aware white man," but that he had fallen in with an "East Coast" set that followed Spencer—"unserious and trashy people: flakes, drunks, drug abusers, women-haters, and embittered, used-up groupies."

Over the years, Johnson and Spencer have sparred. A lot of the conflict, according to alt-righters, had to do with personal style. (Spencer became the best-known face of the "frat" style, polo-and-chinos alt-right; Johnson has dispensed with such pretenses.) But the tension also underscored a debate about how best to save America from itself. In Johnson's view, the far right had to win the war of ideas before it could move on to the "real world" battlefield. That meant books and articles, speaking engagements, conferences, symposia. He had a way of explaining things that made racism and Jew hatred sound like post-structuralism or supply-side economics—something that was once new or avant-garde or even suspect and, over time, acquired a large following.

Spencer was more of a would-be Vladimir Lenin. He wanted to be in the middle of things. He had pondered a congressional campaign in Montana, where he usually lived. He felt let down by Trump. ("His administration is not fundamentally different than a [Mitt] Romney administration—or even a Hillary [Clinton] administration," Spencer said in an interview, "I never expected him to be me. But I expected him to do something") The feeling on the alt-right was that Charlottesville was a disaster because it fragmented the movement. For Spencer, political outcomes mattered.

Both Johnson and Spencer, having been open about their white nationalism, seemed resigned to the ostracism that came with it. Gebert was not that. He was like most alt-righters— especially those who wore a suit to work and had colleagues who weren't white men. He didn't want to be found out. He wore sunglasses to Charlottesville. He reportedly had a rotating cast of anonymous handles: @ TotalWarCoach, @ UnbowedCoach, @ RisenCoach. He built a life for himself and his family around the same kind of mainstream institutions that Johnson and Spencer spurned, and he didn't want to give that up. He wanted white nationalism and his security clearance.

This didn't sit right with Spencer. Gebert's downfall, he told me, "is a lesson on how to be a fellow traveler. You can't do dissident, revolutionary politics in your spare time, or for fun."

Gebert's neighbors were mostly shocked. When the story broke, Gebert was on the board of the Greenway Farms Homeowners' Association and, until recently, had been its president. Soon after, Peter Fedders, who lives in Greenway Farms, organized a Hate Has No Home Here lawn-sign campaign. The HOA bylaws bar lawn signs, but the association's board of directors made an exception. So Fedders ordered 200 signs—signs run $25 apiece if you buy them individually but $5 if you get 100 or more—and, according to another neighbor, threw a "distribution party" at the park that Gebert, as president, had helped create.

When I stopped by the Gebert house in January, a gray-white cat loitered near the door. No one appeared to be home. I was later told that someone at Greenway Farms had texted Anna a photo of me knocking on doors. By midafternoon, yellow buses were dropping off kids. At around 4 p.m., outside lights came on automatically, and about an hour later, commuters started coming home. But not the Geberts.

Recently, there was a Gebert sighting, which created a minor furor on the neighborhood Facebook page. One resident, Brandon Miller, posted: "FYI—everyone's favorite Nazi/White Supremacist, Matthew Gebert, was taking a stroll this afternoon taking pictures of certain houses." Miller included the number of the Leesburg police, just in case. "Obviously not illegal, but just be advised." Other residents wondered whether Gebert was singling out houses that had put up lawn signs. Some board members speculated that Gebert was taking pictures of comparables, real estate jargon for houses valued similarly to his own. Fedders thought that might be the case. Gebert, he said, had "requested HOA documents from the management company," which he said is typically a sign that a homeowner might sell.

At the end of January, Hatewatch reported that, since it published its initial report exposing Gebert, he had hosted 18 episodes of a white nationalist-themed podcast and been a nearly nonstop presence on Twitter and Telegram, and that he's used his old avatar, Coach Finstock. This seemed odd: Now that he'd been exposed, why pretend it wasn't him? "it makes sense," Spencer said in a text. "That's his 'identity.' "

This sparked a new wave of outrage. "To be honest, we're all preparing for the inevitable," one of Gebert's neighbors wrote in an email. "He's casing the neighborhood while pushing the methodology of lone-wolf attacks. While I doubt he has the commitment to do something physically harmful, some alt-right cat on the other end of those podcasts might."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now