Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

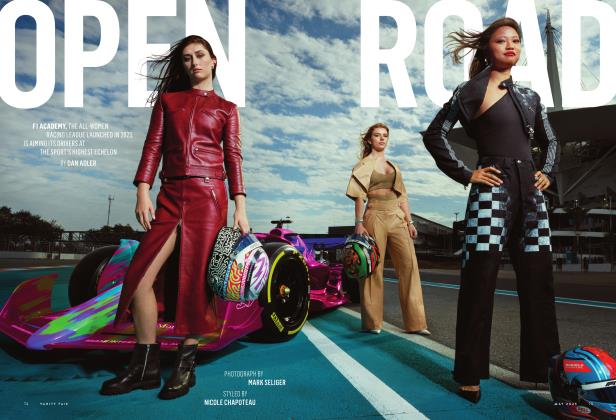

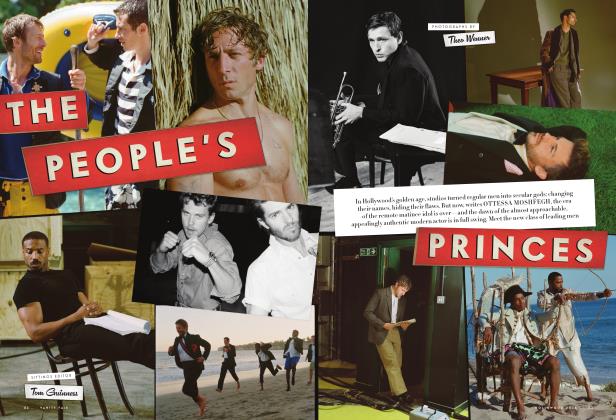

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFORMULA ONE RACING IS OUR LATEST REALITY TV OBSESSION—AND THE MEN BEHIND THE WHEEL ARE SHIFTING INTO NEW LEVELS OF GLOBAL CELEBRITY

April 2022 DAN ADLER NICK RILEY BENTHAM MICHAEL DARLINGTONFORMULA ONE RACING IS OUR LATEST REALITY TV OBSESSION—AND THE MEN BEHIND THE WHEEL ARE SHIFTING INTO NEW LEVELS OF GLOBAL CELEBRITY

April 2022 DAN ADLER NICK RILEY BENTHAM MICHAEL DARLINGTONIn 2019 the French Formula One driver Esteban Ocon found himself locked out of the competition. The year before, the Canadian billionaire Lawrence Stroll had bought Ocon's team, rebranded it, and dropped Ocon as one of the organization's two drivers in favor of his son, Lance. The world of F1 is small, with only 20 drivers competing for 10 teams each season. Ocon wouldn't be one of them.

Then his star began to rise.

Norris streams some racing on Twitch, where he and a few peer drivers passed the time during coronavirus lockdowns by gaming for an online audience. "I don't think you would necessarily see the older generation doing this kind of thing," the British driver says. "I think we're more open to being seen publicly and giving fans that kind of experience."

Ocon had featured prominently in the first season of the Netflix documentary series Drive to Survive, which began filming in 2018. The show offers fans a previously unseen level of access to the most rarefied of motorsports, stretching its global reach in the process. The drivers who had participated in that first season were no longer just semi-interchangeable athletes behind mirrored visors at the wheel of multimillion-dollar cars, but protagonists in a high-stakes (and soapy) drama set against the backdrop of a tour that spans five continents each season, with stops in Monaco, Sao Paulo, Abu Dhabi, and more.

The combination of charismatic drivers and far-flung locales proved a major draw to an antsy viewership stuck at home over the last couple of years. Already famous in their field, Ocon and many of his cohorts became crossover celebrities for new audiences in the course of months (especially in the U.S., the leading market for Netflix; a spokesperson for the company said the third and most recent season of Drive to Survive attracted its largest audience to date). This certainly did not hurt his path back to the circuit, where he now races for Alpine. "To be in the spotlight at a time when it was quite quiet for me," Ocon told me in a recent interview, helped with "raising questions and bringing me back into conversation with the bosses."

After more than a decade in F1, Ricciardo, an early star of Drive to Survive, has enjoyed seeing a new audience for the sport, including in his native Australia. "Why shouldn't we let them in?" he says. "Why shouldn't we let them see the highs and lows and the emotions?"

For the record: There are no hard feelings. Ocon, 25, said he counts Lance Stroll, 23, as one of his closest friends in the competition. That's all part of the show's appeal. A sizable portion of today's F1 athletes grew up racing go-karts against each other, and the sport's field of drivers is at its youngest ever at a moment when its individual personalities and the relationships among them have come to the fore.

"A third of the grid is guys I've known all of my life," British driver George Russell, 23, said.

DRIVERS WHO HAD PARTICIPATED IN THAT FIRST SEASON WERE NO LONGER JUST SEMI-INTERCHANGEABLE ATHLETES.

"They're laughing about TikTok videos," Australian driver Daniel Ricciardo, a relative elder statesman at 32, said. "We're laughing about Jim Carrey movies." But Ricciardo, more than a decade into his career, has embraced the new phase of F1 too, describing himself as "good-looking" in some episodes of Drive to Survive and "feeling like the smallest guy in the whole of F1" in another.

F1 is a team sport, with hundreds working at each automaker. But fandoms tend to happen on the personality level, as rivalries between drivers sprawl out over seasons and become defined by their psychological intricacies as much as race results. Athletes compete for the championship, as well as for a rotating set of limited-supply contracts with the likes of Ferrari and Aston Martin. Even teammates represent competitive threats to one another.

In coming seasons, Ocon plans to change his helmet design to look more futuristic. "I'm maybe a little bit more the old-school driver who is more focused on the racing side and a little bit less on the image," he says, "but I'm coming towards that direction as well."

"I was never really into F1 until the Netflix show," fashion designer Sandy Liang said when I spoke to her earlier this year. She began watching Drive to Survive as the coronavirus pandemic took hold in 2020 and became hooked by its second episode. In it, Ricciardo and the Dutch-Belgian driver Max Verstappen, then teammates at Red Bull Racing, collide during the Azerbaijan Grand Prix. Ricciardo spends the following episodes brooding over his future at the team, a process which he sometimes narrates himself during filmed conversations with his manager or in a voiceover while he solemnly stares over a body of water.

"After watching the thing between Daniel and Max..." Liang recalled. "Wow. This is drama. This is hot."

WHERE THE SHOW IS LIGHT ON THE INTRICACIES OF PIT STOPS, IT LINGERS ON ANY HINT OF A FEUD.

Last year, she held an F1-themed party for her 30th birthday (including cutouts of the drivers and a go-karting component), attended the Austin Grand Prix with a group of fellow converts, and worked a riff on the sport's logo into one of her collections.

"I'm so invested because I follow their social media and I feel like I know them through the Netflix show," Liang said, "even though I know for a fact that it's overdramatized just like all the reality TV shows."

Russell trained with Mercedes beginning in his teens and will now represent the team as one of its two senior drivers. The rise of his generational cohort has added an extra degree of familiarity to the F1 field. "When the helmet's off, everything's cool," Russell says. "Unless there's been history there."

Before Netflix ever made an episode of Drive to Survive, F1 revolved around a caravan of sparring scions and ambitious upstarts. After each Sunday race, the sport packs itself up and heads to a new country, where another sideshow of local and imported celebrities awaits. For decades, British billionaire Bernie Ecclestone molded the sport around an earlier entertainment product when he put broadcast TV rights at the center of F1's business agenda. Then in 2017, American company Liberty Media acquired F1's parent organization and set out to build a new audience for the sport.

The following year, the production company Box to Box Films began taking the material on hand and setting it to dramatic rhythms familiar to viewers of Laguna Beach. Where the show is light on the intricacies of pit stops, it lingers on any hint of a feud. Occasionally, it takes viewers into the day-to-day life of a post-Spice Girls Geri Halliwell, who is married to Red Bull's team principal Christian Horner.

Some accusations of sensationalism aside, the show has been, by most accounts, a boon to the sport.

At first, Gasly found it awkward to watch his seasons play out on television. But the French driver began to settle into the circumstances, in part because they comport with his own habits: "I must say, I do watch a lot of Netflix. I'm a good consumer."

"I've had calls from most of the other major leagues," Zak Brown, the CEO of McLaren Racing, said. "How can we get on Netflix?"

Brown, for one, said he hasn't minded the cameras.

"I don't think you can be in the public eye and have a sport that's built for the fans and then get annoyed because you're being followed," Brown said. "That's what we signed up for."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now