Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Chan of Heart

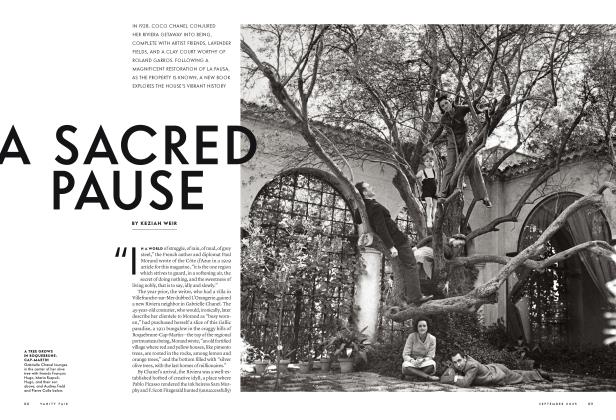

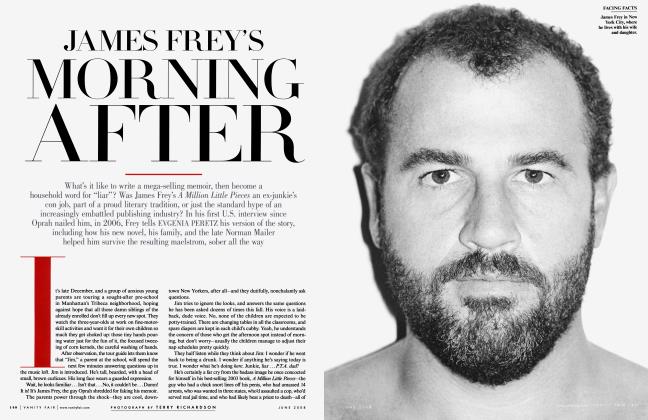

EVGENIA PERETZ

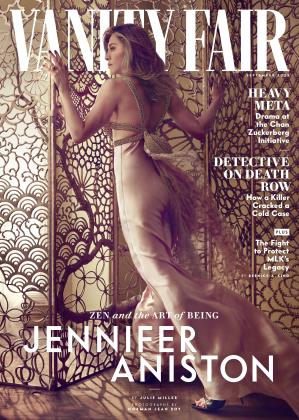

In 2015, Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan built a philanthropic behemoth in their image: the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Science-forward, research-backed, driven by empathy. But as Zuckerberg and Meta have tacked right, ditching DEI, insiders say Chan has become a proxy figure in the battle between her husband's company and their progressive CZI staff

PRISCILLA CHAN MET the moment with the kind of grace and sensitivity she'd become known for. Itwas July 2020, George Floyd had recently been murdered, and staffers at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative—the foundation she started with husband Mark Zuckerberg in 2015—were hurting. Tissues on hand, eyes welling up, she hosted an all-hands Zoom to address them. " It didn't feel right to not actually just spend the time as an organization acknowledging the—in medicine we call it 'acute on chronic'—racial disaster that is our coun-

try," she said, hands clasped in front of her, in a video obtained by Vanit), Fair. If there was a silver lining, it was that the moment was so bad, change was imperative—both in the country at large and at CZI, whatever that would entail. "That's my little hopeful pearl that I want to try to add.... We stand with the Black community, we stand with our Black employees. It's felt harder and more important than ever to get a lot of our work right." The work would take time, she acknowledged, but she implored her employees to "take care of yourself, make sure you're giving yourself the space, the grace."

Four and a half years later, Chan appeared at President Donald Trump's second inauguration, alongside her husband on the dais, a spot usually reserved for the president's nearest and dearest. Zuckerberg had been cozying up to MAGA world for some time and had just come off an appearance on Joe Rogan's podcast where he, buff and in a new gold chain, ragged on the Biden administration and lamented a lack of "masculine energy" in the workplace. But to some, Chan looked uncomfortable at the inauguration, and the optics weren't computing. Through CZI, she'd spent hundreds of millions on biomedical research, yet here she was standing a few feet from Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the new secretary of health and human services, a science skeptic. She appeared to make small talk with Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who was soon to cut billions in foreign aid, including for lifesaving HIV treatment in Africa. To many of Chan's colleagues and admirers from the philanthropy world, the image was distressing.

To them, Chan represented—perhaps still does, they hope—everything antithetical to the president she was honoring. If Trump was their idea of a nightmare billionaire, Chan was their dream. They knew her to be unflashy and disciplined, driven by the conviction that everyone deserves a chance to overcome the circumstance of their birth. She was profoundly empathetic, easily moved to tears at the suffering of others. What could she have been feeling, some of those contacts wondered, celebrating such a gleefully callous man? Later, Zuckerberg posted a photo of the two of them in black tie on their way to an inauguration party he was cohosting with the caption, "Feeling optimistic...."

Seven months into the administration that appears to be gutting everything she has held dear—scientific research, higher education, public health, caring for those in need—it's hard to imagine that Chan, at least, is feeling optimistic, but she has remained largely silent. (Chan declined to be interviewed for this story.) Many former colleagues and admirers from nonprofit circles are searching for signs of the woman they knew and floating the questions. "I know they are separate people—and frankly, Priscilla comes off as a lot more human than Mark," says Lucia Reynoso, a former CZI engineer, "but they are married and gave the impression of a united front." So is she aligned with her husband? Has she been ideologically moved by the right-wing plutocracy? Or is she still working toward the greater good, maintaining her silence out of a sense of pragmatism?

"It's not like she was a critical race theory expert.... But she always took the posture of, all right, I'm willing to learn... and I want to do the right thing. She seemed very genuine about wanting to get it right."

IF TRUMP HAD been president 50 years ago, Chan's parents might never have found their way to this country. They were ethnic Chinese immigrants from Vietnam who had each fled the war-torn country by boat. They met upon arrival in the US, married, and settled in the working-class neighborhood of Quincy, Massachusetts. They worked in a Chinese restaurant and raised three daughters. Priscilla was the eldest. At the local public high school, Chan excelled in science and on the tennis court, became valedictorian, and got into Harvard on a full scholarship—the first person in her family to go to college.

It was there that she met Zuckerberg in October 2003, standing in line for the bathroom at a frat party. It was not his finest hour. He had just built Facemash, his "who's hotter" website featuring images of Harvard girls side by side. The site had spread like wildfire on campus, and now he was set to go before Harvard's Administrative Board. But one can imagine he fulfilled a need in Chan. She'd felt a sense of awe and alienation upon getting to Harvard, what with all the privileged, hypereducated kids in private school cliques. But here was one such boy, who'd gone to Phillips Exeter Academy, and he was interested. He was a brilliant nerd who, she found, "speaks in a whole new language and lives in a framework that I've never seen before," as she told The New Yorker in 2018. He spent the months after they met building Facebook from his dorm room, then dropped out to go to Silicon Valley. Meanwhile, her life path presented itself to her when she met a girl from the Dorchester housing project, where Chan was mentoring. The girl's front teeth had been knocked out. It was heartbreaking to Chan, a biology major, and it confirmed to her a calling—to serve children in need.

After she graduated in 2007, she joined Zuckerberg in San Francisco, where she taught science at an elementary school and then began medical school at UCSF. As a condition to her move, she made him commit to one date night a week and 100 uninterrupted minutes away from Facebook. He was then growing Facebook at warp speed—he'd turned down an offer from Yahoo to purchase it for $1 billion, and now, after an investment from Microsoft of $240 million, the company was valued at $15 billion. Chan told The New Yorker, " I had to realize early on that I was not going to change who Mark was." But she could try to guide him in a world of real-life humans. They spent weekends together doing earnest activities like watching their favorite show, The West Wing (created by Aaron Sorkin, who would go on to write the screenplay for The Social Network), and playing Settlers of Catan, and in 2010 she moved in.

In a subsequent Zoom meeting, Zuckerberg himself One after another, they gave emotional pleas, expressing

By that point, roughly one out of every 12 people across the globe had a Facebook account. Its promise was epic—to do nothing short of connect the entire world, and to help people "maintain empathy for each other," as he told Time magazine, where he was named Person of the Year at age 26. In line with his status, Zuckerberg began honing his legacy. His hero had been fellow tech billionaire Bill Gates, who in 2010 launched the Giving Pledge, challenging other billionaires to promise to give away at least half of their fortunes before death. " I encouraged them to start early," Gates says of early conversations with both Zuckerberg and Chan about philanthropy, noting that "Priscilla is leading one of the most ambitious scientific and philanthropic organizations in a generation." Taking his cue, Zuckerberg announced with fanfare on The Oprah Winfrey Show that he would be donating $100 million to Newark public schools. The results of that effort were mixed, which educators have attributed to the project's insufficient collaboration with the community. (A CZI spokesperson disputes the criticism, pointing to independent research that found improvement in graduation rates and gains in student achievement.)

Chan later told him that if he was going to be serious about education, he should probably have some real-life experience teaching. At her urging, he gave it a whirl byteaching a class on entrepreneurship at a Boys and Girls Club. Meanwhile, Chan was all in, doing high-stakes trauma work at San Francisco General Hospital. "It was gunshot wound after gunshot wound," recalls a close friend. "She was the friend who's always exhausted after doing a double shift." She also took part in a special UCSF program designed to improve the health of underserved children. Facebook went public on May 18,2012. Chan and Zuckerberg, now worth an estimated $19 billion, married the next day.

IN 2015 THE couple began two major projects, which they made a point of connecting: CZI and their family. After multiple miscarriages, Chan was pregnant with their first child. According to the recent memoir Careless People by former Facebook employee Sarah Wynn-Williams (whom Meta has legally blocked from personally promoting the book on the basis that she has potentially violated her contract), while Zuckerberg and his team were in Indonesia, he floated the idea to his coworkers that he might not be present for the birth—not that there was any particular conflict, just that something more important might come up at work. He relayed that he'd spoken with Chan about the possibility. As Wynn-Williams claimed, "[Chan] told Mark that she would be totally fine with him skipping the delivery but that he might come to regret missing the birth of his first child." ("Mark was, of course, present from the beginning to the end of all three hospitalizations and deliveries for all three of their children," says a source close to the couple. "This was not something they discussed.") A few months before the birth, in September 2015, Zuckerberg attended a White House dinner and spoke with President Xi Jinping of China, where he was desperate to launch Facebook. Wynn-Williams claimed that he asked if Xi would do him the honor of naming his unborn child. Xi declined. They ended up naming the baby Maxima—"Max." Zuckerberg had long been fixated by the Roman emperors and would go on to name their other two daughters August and Aurelia. (Careless People "is a mix of out-of-date and previously reported claims about the company and false accusations about our executives," a Meta spokesperson said upon the book's publication.)

joined Chan, and staffers' complaints snowballed, their feeling that he had betrayed the company's values.

Max's birth coincided with the unveiling of CZI, which shook the philanthropy world. At its founding, the couple wrote a public letter to their new baby that both spoke of the promise of science and was suffused with Obama-era feel-good progressivism. "Our hopes for your generation focus on two ideas: advancing human potential and promoting equality," they wrote. "Promoting equality is about making sure everyone has access to these opportunities—regardless of nation, families, or circumstances they are born into." They announced they would be giving away 99 percent of their shares in Facebook in their lifetime, then valued at $45 billion, to the organization.

The mission was to fix almost everything. On the science front, CZI would help "cure, prevent, and manage all disease over the next century." To Cori Bargmann, the first CZI head of science, that audacious goal was a meeting of the couple's essences: Zuckerberg the big-thinking engineer, and Chan, the pediatrician, driven to find the often-elusive answers to ailments afflicting young patients. "She was really motivated by this idea to help children," says Bargmann. "And there were just children you could not help, because there was no help. And for her, science is hope." CZI zeroed in on the goal of creating a " Human Cell Atlas," a reference for understanding every single cell in the human body, of which there are 37 trillion. CZI wouldn't just make grants, it would also create tech tools and form its own " Biohubs"—research centers bringing together scientists at the top universities. According to Sam Hawgood, chancellor of UCSF and a CZI Biohub Network board member, CZl's big-picture goal set it apart from other biomedical philanthropies that might focus on a single disease. "The great thing is their recognition that big breakthroughs in health come from long-term investments in fundamental, curiosity-driven science," Hawgood says.

Chan has done what she felt she had to do, "I think at the end of the day, they are both

On the "promoting equality" front, they would remake public education and take on immigration and criminal justice reform, housing, and community. They laid out their ethos to baby Max: "if you fear you'll go to prison rather than college because of the color of your skin, or that your family will be deported because of your legal status, or that you may be a victim of violence because of your religion, sexual orientation, or gender identity, then it's difficult to reach your full potential." It was personal to Chan, who would mn the day-to-day operations, while Zuckerberg would advise. She had been lucky, she often said, to have had teachers who believed in her and nurtured her, but it was fundamentally unjust that people needed luck to have access to opportunities.

T-shirts were made: "A Future for Everyone." Scientists, nonprofit types, and left-leaning politicos flocked to work for them, like Obama adviser David Plouffe, who would run the Justice & Opportunity Initiative, and Jim Shelton, who worked in the Obama Education Department and came on to lead CZl's Education Initiative. It was like their beloved West Wing, but set at a charitable endeavor with limitless funds. The office, a single open space in downtown Menlo Park, was casual and nonhierarchical, a tone set by Chan, early employees recall. Even though she had some security measures in place for herself, she was approachable. Her desk was out in the open, and she chatted like any regular employee—about kids, the martial arts class she was taking, pop culture. The couple made concerted efforts to bring staff into the fold, to ask whatever they wanted in a weekly all-hands meeting. Chan, in particular, was an active listener. Maurice Wilkins, who was head of DEI until he left in 2019, recalls, "it's not like she was a critical race theory expert, any of that stuff. But she always took the posture of, all right, I'm willingto learn...and I wantto do the right thing. She seemed very genuine about wanting to get it right."

And she pushed herself further, opening her own CZI-funded school with the late educator Meredith Liu for the most underserved children of East Palo Alto, near Facebook's first offices. It was called the Primary School, and it would focus on "the whole child," integrating health, social-emotional learning (SEE), and family support. Akimi Gibson, at the time a VP at Sesame Street workshop, which consulted with the school on SEE, recalls, "She spoke emphatically and passionately about the relationship between health, education, and poverty." The tech boom in Palo Alto had driven real estate prices up, forcing an exodus of poor and working-class people. According to Gibson, "it was clear she was aware of our concern about the reputation of Facebook displacing families, as many families were vulnerable—living in cars or their vans, and with little resources."

Still, CZI insisted to people inside and outside the organization that it ran independently of Facebook. Staffers understood that they shouldn't get too bent out of shape by, say, learning that Zuckerberg had met with Trump. "There was a lot of grace for Priscilla," says Ray Meadows (formerly Holgado), a former grants manager in CZl's Justice and Opportunity division. "I think folks gave her the benefit of the doubt for a long time." But with a shared CEO in Zuckerberg, it was increasingly hard for many to escape the sense that Facebook loomed over everything, especially when things started going sideways.

according to sources who know her intimately. practical people" is how one close friend puts it.

In 2018 CZI had to contend with the fallout from the Cambridge Analytica scandal, the revelation that a Trump-aligned political consulting firm had gathered data from 87 million Facebook users without their consent and targeted them with personalized ads prior to the 2016 election. Zuckerberg was dragged before Congress for the first time, where he was grilled not just about the company's privacy practices but about the platform's addictive nature, and how it was coarsening the public discourse and contributing to ethnic violence, particularly in Myanmar, where a genocide was taking place. Senator Lindsey Graham took him to task for the company's 2016 internal memo, written by then vice president of Facebook Andrew Bosworth—subject line "The Ugly''—that read in part: " We connect people. Period... That can be bad if they make it negative. Maybe it costs someone a life by exposing someone to bullies. Maybe someone dies in a terrorist attack coordinated on our tools. And still we connect people. The ugly truth is that we believe in connecting people so deeply that anything that allows us to connect more people more often is Me facto* good."

Zuckerberg came through with what was widely regarded as a slap-on-thewrist fine for Facebook; a few days later, he was even some billion dollars richer. But his reputation was bruised, and some at CZI worried that its image would be bruised by association and that CZI needed to work harder to distinguish itself from Facebook. Thatworkappearedto fall to Chan, who shied away from the spotlight but now seemed to take on a more robust role as the friendly public face of the organization. She went on CNN, for example, where she emphasized that the company was "majority women," as B-roll showed women in a conference room laughing. On the Today show in 2020, she took the opportunity to come to her husband's defense. "Seeing him at home and in his work grappling with these massive questions that sometimes don't have clear answers," she said, "I am proud of how he's been handling all of this and I know he's doing his hardest and I wish others could see it." (A CZI spokesperson says that Cambridge Analytica "had no impact on Priscilla's role at CZI, which has always been to serve as the day-to-day leader of the organization, including speaking publicly about CZl's work.")

But more controversy was brewing behind the scenes at Facebook that cut ever closer to the bone of part of Chan's life's work—children's health. In 2019 and 2020, Facebook's internal research demonstrated that its app Instagram was harming teenagers, with conclusions such as: "We make body images worse for one in three teen girls" and "Teens blame Instagram for increases in the rate of anxiety and depression." Another finding stated that among teenagers with suicidal thoughts, 13 percent of British teens and 6 percent of American teens traced those feelings to Instagram. Until Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen leaked to The Wall Street Journal in 2021, in what became part of the paper's series The Facebook Files, the news had not made its way to the public. Zuckerberg, Haugen later testified, had been reluctant to take the steps necessary to address the problem; more safety meant less time on the platform, and thus fewer ad dollars. (The Facebook Files will be the basis for Aaron Sorkin's upcoming follow-up to The Social Network, which he will also direct. A representative for Sorkin did not respond to Vanity Fair as to whether Chan will be depicted.)

PRIORTO THE scandalbreaking, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt was studying social media and its adverse effect on kids for his future book, 2024's groundbreaking The Anxious Generation, and got to know the couple. Chan admired him so much for his previous book The Coddling of the American Mind that she invited him to dinner with her and Zuckerberg; a source close to the couple points out that "Markand Priscilla regularly invite people from all different backgrounds to visit and share their perspective." Zuckerberg indicated that he disagreed that there was any causal relationship between social media and mental health and insisted there was no scientific consensus on the matter. Later, Meta would lobby against the bipartisan Kids Online Safety Act, while Haidt would comment that Zuckerberg "does bear some personal responsibility" for a spike in suicides among children who used Facebook's apps.

Chan, it seemed, took her husband's side on the matter. In 2020, when asked on the Today show about social media platforms and how parents can protect their children, she replied, "With everything where there is physical danger or threats to their mental health, you teach them how to use it, use something safely.... As a parent I also need tools. You might be looking at their social media. Or whatever it might look like. We need to monitor, have a gradual release, and expect tools to help us along the way." In other words,parents should police what their kids are seeing on Facebook, not the company, as if parents could possibly regulate the all-powerful algorithm.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 110

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 77

In the summer of 2020, after the murder of George Floyd, Facebook's controversial actions came crashing through the doors of CZI. In response to the protests, Trump had posted on Facebook, "When the looting starts, the shooting starts." Despite public outcry to stop Trump's incitement of violence, Zuckerberg and his team at Facebook made the decision to keep it up. More than 140 CZI-funded scientists wrote a letter to Zuckerberg, arguing that Facebook had violated its own guidelines and that "the spread of deliberate misinformation and divisive language is directly antithetical" to CZl's stated mission. Chan and Zuckerberg responded with a statement stressing that CZI was separate from Facebook and that it remained committed to an " inclusive, just, and healthy future for everyone."

But that didn't contain the matter. Nor did Chan's emotional promise to the staff over Zoom that she and Zuckerberg stood with the Black community. A question was asked about Zuckerberg "stoking the flames of racial violence on Facebook," and Chan tried to assure them, again, that " We are two separate organizations.... But I want you to know that Mark feels very similarly to how I do about the current situation."

In a subsequent Zoom meeting soon after, Zuckerberg joined Chan, and staffers' complaints snowballed. One after another, they gave emotional pleas, expressing their feeling that he had betrayed the company's values. One said she was losing sleep over decisions Facebook was making; another went so far as to ask Zuckerberg if he would consider stepping down from either CZI or Facebook. He seemed unfazed by this. " We believe that Black lives matter. And that it's important to say that, and I have said that," he told them. " We also need to get through this moment in a way where we have our values intact going forward. And for me, a lot of what that means in a democracy is supporting giving people a voice even when you do not like what they say." Chan tried to remind people, yet again, that the work CZI was doing had nothing to do with her cofounder's other job. "This is not what we work on at CZI," she said. "The collective mission at CZI is what I want to lead us to go charge at." But the message no longer seemed to fly. A scientist pressed Zuckerberg about who exactly was making content decisions at Facebook and how. In response, Zuckerberg tried to assure the group that the company's "automated systems" were on top of it: "Making sure we're proactive about reducing harm on the platform is a huge priority," he said. "There are about 20 categories of harm that we track...."

"His responses really felt like an insult to the intelligence of CZI employees," recalls Reynoso, the former CZI engineer, who says she was one of the more confrontational people on the Zoom. "I would have rather him come out and just say he was letting Trump flout Facebook's rules out of political expediency."

In reaction to what they were hearing, and wanting to be part of the Black Lives Matter efforts, the couple announced that CZI would make a $500 million commitment to leaders and organizations that supported racial equity. It would launch, for example, a partnership with four historically Black medical colleges and a science diversity leadership program to fund historically underrepresented faculty in biomedical services. As the couple wrote in its annual letter that year, "We started CZI because we believe everyone deserves the chance to reach their full potential. But systemic barriers have long denied many Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people that chance." In line with this awareness, when COVID hit, CZI stepped up with large-scale testing, particularly in underserved areas of California. "The legacy systems just weren't ready to do that," says Bargmann.

At the same time, however, there seemed to be growing concern over political optics, according to multiple former staffers—so much so that the communications department was one of the approving parties for grantees. (A CZI spokesperson says, "Like in any other organization, communications is a strategic function whose work is wholly in service of our programmatic goals. F inal decisions about programmatic grants are made by the respective leaders of our initiatives in alignment with strategy.") Meadows recalls that his team would sit in front of a whiteboard, where grantees were classified by left, right, and center. "If we fund the ACLU, then we have to fund Y [meaning a Y factor, not the YMCA]. We knew we had to offset things constantly" is how he characterizes the thinking. "We're not looking at these things and asking what the best solution is. We're looking at what's going to rock the boat the least, and, in my mind, won't disrupt Facebook's business interests." (Meadows left the company in September 2020 and shortly after filed a racial discrimination complaint against CZI. CZI responded that the claims "were previously raised internally, independently investigated, and found to be unsubstantiated.")

Indeed, Chan and Zuckerberg drew criticism for donating some $400 million for safe voting booth infrastructure during the pandemic—even as Facebook became a prominent platform for spreading anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. Republicans, claiming that the donation was a partisan effort to help get Democrats elected, called the donation "Zuckerbucks," and Trump blamed Zuckerberg for helping Biden win the 2020 election. Other billionaires might have laughed off the complaints. But Chan and Zuckerberg scrambled to change tacks. In 2021, after rebranding Facebook as Meta, the couple hired Brian Baker, a prominent Republican strategist, to seemingly help repair relations with Trump and his allies. They publicly announced that the voting infrastructure donation was always intended to be a one-time thing and that they had no plans to repeat it. And they took their first baby steps away from work that had the whiff of activism.

Starting in 2021, CZI spun off its work in criminal justice and immigration into two separate organizations, the Just Trust and FWD.us. Two years later, they wound down education advocacy, shifting its focus in that arena to AL The moves were subtle, but among its idealistic staffers, something was getting lost and Chan was harder to reach.

According to one, in meetings she seemed to be deferring to Zuckerberg more and more, and folks began asking one another everyday, "Who has Priscilla's ear?"

And then Trump was back. In the lead-up to the 2024 election, Zuckerberg had been confronting an FTC lawsuit for allegedly maintaining an illegal monopoly, a suit that could force Meta to break up and potentially knock down his estimated $207 billion net worth. He'd tried to stave it off with a settlement but was unsuccessful. Now, following Trump's victory, CZI staffers watched with dismay as their cofounder steadily made his MAGA transformation— from his invitation to Dana White, UFC CEO and Trump pal, to sit on the board of Meta; to his announcement that Meta would rid itself of fact-checkers; to showing up on Joe Rogan's podcast sporting his new manosphere look. The comment to Rogan that the workplace could use some more "masculine energy" particularly rankled; at least one person wondered how Chan could have abided it. According to another source, when a question was raised at CZI about Meta's $1 million contribution to Trump's inauguration, the response came down: That's Meta's prerogative and it has nothing to do with CZI.

Curiously, however, the moves CZI then took were precisely in line with what Zuckerberg needed to remain in good favor with the current administration. CZI stopped funding the two social justice organizations it had spun off four years earlier. In January, after Meta announced that it would end DEI hiring practices, CZI assured worried staffers that decisions made at Meta would have no impact. But a few weeks later, after Tmmp issued an executive order targeting DEI, CZI followed suit, closing its DEI team too. Dozens ofgrantees' plans for the future have been thwarted. Buttoning up that entire era, the Primary School announced it would be shuttering—a CZI investment that had once been celebrated for lifting up the most underserved children of the community. (CZI said it would donate $50 million to the community, in part to assist impacted families.) A source with knowledge of the situation says that the school had no endowment and had failed to scale, which was part of its original goal. In May the editor in chief of Inside Philanthropy, David Callahan, wrote, "I can't recall another mega-donor couple backtracking so completely from their early ambition."

Former DEI head Maurice Wilkins has watched with dismay as Chan's foundational passion—to take luck out of the equation—seems to have fizzled. "That idea has completely disappeared," he claims. "And so my assumption is that they decided that they want to do what's in the best interest of remaining the richest people in the world." Reynoso, the former CZI engineer, echoes that view. By the time she left, it felt like Chan was serving the purpose of helping Zuckerberg "launder his wealth into prestige.... It felt like we were becoming a place where any benefit to wider society was a secondary effect."

This has all necessitated something of a public rebrand for CZI, which involves downplaying the "promoting equality" thing—the idea once central in their letter to Max was not that important in the first place. When asked in March about CZl's turn from some social issues by an interviewer at SXSW, Chan said, "I want to note that we've honored all of our existing commitments," and added, "The reality at CZI is that these policy changes affect a very small percentage of our overall work." In June she addressed the criticism more directly in a letter on CZl's website: "I'm still guided by the same values I've lived by my entire life, and that I work every day to pass on to my daughters: optimism for a better future, hard work to make that future possible, and a deep commitment to helping others. The changes we've made at CZI will allow us to ensure our work does the most good and achieves the greatest possible impact."

Chan has done what she felt she had to do, according to sources who know her intimately. "I think at the end of the day they are both practical people" is how one close friend puts it. Another source close to Chan says of her choice to attend the inauguration, "Turning discoveries in basic science research into treatments and cures that impact millions of people requires deep partnership with the federal government and private industry. Like many executives, Priscilla sees value in engaging with leaders in both parties and across sectors to advance CZl's mission."

According to CZI Biohub Network board member Hawgood, progress has been made in the Human Cell Atlas. The next step in its migration would be to build "digital cells" for scientists to study; that would require AI to process multitudes of data sets. It's too soon to tell if what CZI calls the Virtual Cell Model will one day come to fruition, "if it could be achieved, it would be a breakthrough along the lines of the human genome project, or something of that magnitude," says Hawgood. Gates, whose own foundation has collaborated with CZI over the years, praises CZI for "accelerating open, collaborative biomedical research and putting AI tools in the hands of scientists" and believes that its achievements will have lasting impact. In July CZI announced the opening of a new center, in partnership with Nobel Prize-winning biochemist Jennifer Doudna, to treat rare genetic diseases in children using CRISPR gene-editing therapies.

Yet the Trump administration is eviscerating the ecosystemof science onwhich CZI relies. Trump's budget called for a $18 billion cut in the NIH budget, threatening biomedical research across the country. The administration has already canceled or frozen grants for roughly 2,500 projects tackling cancer, Alzheimer's, and chronic diseases. The best young minds from China, India, and any other foreign country may not be allowed to attend Harvard, Chan's alma mater.

Two board members of the CZI Bio -hub Network are sounding the alarm, albeit diplomatically. University of Chicago president Paul Alivisatos—a distinguished nanoscientist who joined the board in 2023—explains: "I think we've had for decades now a kind of compact between the public, the universities, biotech companies, medical companies, large academic medical centers, and also foundations and nonprofits. We've had a kind of compact where we all contribute in different ways to what has been really the most successful biomedical discovery that the world has ever known. And I think it's very precious," he says. Hawgood echoes the sense of urgency. "An $18 billion cut in a $47 billion NIH would be devastating, not just devastating to a place like UCSF," says H awgo 0 d. " My gre ate r co nee rn is that it's going to be a threat to the US dominating the world in science going forward.... Now is the time for advocacy."

Might the couple participate in such advocacy themselves? Hawgood says, "I think they're making a statement in where they're putting their own money, and that is into the fundamental science. In terms of what they do from apolitical advocacy perspective, it's not my role to tell them what to do or even suggest to them. It's just as it is my personal decision what I do. I respect their privacy and their own decision making on that subject."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now