Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBROKEN ARTED

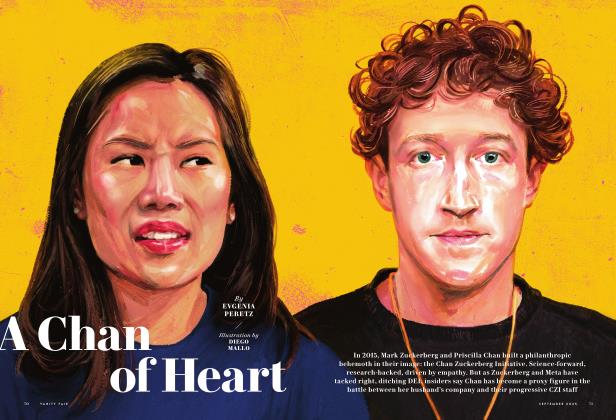

Barbara Guggenheim and Abigail Asher were, until recently, grandes dames of the art market, outfitting the most powerful people in the world with killer portfolios. Then, in a flurry of mutual allegations ranging from sexual favors to fraud, the two women parted ways. As their battle heads to court, EVGENIA PERETZ reports

EVGENIA PERETZ

Sitting with Barbara Guggenheim in the stately, well-appointed living room of the Park Avenue apartment that she shares with her second husband, the wealthy venture capitalist Alan Patricof, one feels as if in the presence of a Sargent portrait, if he were painting in sunblasted, minimalist 2025. Guggenheim is dressed beautifully in a crisp midi-length white skirt, white sweater (both by Attersee, a brand founded by her niece Isabel Wilkinson Schor), and white Loewe sneakers. The look matches her sleek white-blond hair pulled back in a clip. At 78, her face is as unlined as that of a 40-year-old, her jawline exquisitely sharp. From the viewer's position, Guggenheim—the pioneer and grande dame of the rarefied field of art advising—looks every inch the woman who has achieved it all and wants for nothing.

She didn't have children, but she had a younger woman in her life: her business partner Abigail Asher, who may as well have been a daughter. Together, over the course of more than three decades, they filled the homes of billionaires and celebrities (Tom Cruise, Steven Spielberg) with work of blue-chip artists while elevating the hallways of megacorporations like Coca-Cola and Sony. "I considered her almost a part of my family," Guggenheim says. "I even personally paid for a part of her son's school tuition. That was not a loan—it was my gift to them."

That was years ago, before Guggenheim and Asher's professional love story exploded in the worst kind of divorce—with dueling legal complaints, personal attacks, and scandalous claims about sex and corruption. Guggenheim is alleging that Asher stole from their company to fund her lifestyle and that she launched her own competing advisory in secret. Asher is countering that it's Guggenheim who dipped into the business, and that she had been "bullying, threatening, and gaslighting" Asher for the better part of her career. Both women are aghast at the other's claims. Art world colleagues, still reeling from the conviction of top art advisor Lisa Schiff for defrauding clients out of millions, are in fresh states of shock. After all, the two women were a bedrock of the industry and seemed to be the perfect match. Guggenheim was the high-flying, glamorous face of the firm, giving lectures around the country, pairing masterpieces with masters of the universe. Asher was the younger, serious Brit working out of New York, bringing in a new generation of moneyed clients and nurturing them with care and fastidiousness. "It really did seem at the time like a match made in heaven," says LA art adviser Patricia Peyser, who has worked closely with them for 20 years, and admires them both.

Now, big-league names on both sides are jumping to each woman's defense. "Abigail's as honest as the day is long, an absolute stickler for form," says longtime friend Adam Chinn, former COO of Sotheby's, who's done multiple deals with her. "She's professional to the point of being beyond meticulous. " As for Guggenheim, her close friend Michael Ovitz, CAA cofounder and a major collector, says, "She's one of the most trustworthy people that I know. I've never ever in 45 years caught her in anything duplicitous, any fibs, any storytelling, any lack of integrity. And Abigail's trying to destroy her at this time is just crazy."

Indeed, Asher's complaint is the more personal of the two. And today Guggenheim is stung. It was filled, Guggenheim says, "with vindictive, crazy lies, and exaggerations that were very dismaying to see, very upsetting from someone I had had a relationship with for three decades.... There's only personal allegations and character assassination." As Guggenheim continues talking back in the Park Avenue apartment, the iciness melts—her voice shakes at times and her blue eyes evince vulnerability. The impression of her shifts to lioness in winter, doing her best to keep her head high and hold on to her name and reputation as the woman who put her industry on the map.

Guggenheim is not related to the Guggenheim museum family—though having that name couldn't have hurt. She didn't come from wealth. Her father was the owner of dress shops in Woodbury, New Jersey. In 1968, when she moved to New York to start on her master's in art history at Columbia, there was just one major gallery in SoHo, the Paula Cooper Gallery. She worked her way through graduate school by giving talks at the Whitney Museum every Saturday and Sunday about whatever art was up. One day in the mid-1970s, one of the women in the group asked if Guggenheim would take her to SoHo to visit some galleries; by now more were popping up in the increasingly exotic neighborhood, filled with the world's most avant-garde characters—think SoHo circa Martin Scorsese "s After Hours. As uptown's guide through this exciting demimonde, Guggenheim could see that she was on to something. In 1975 she started her own business, Art Tours of Manhattan, taking locals and tourists to museums, galleries, and artists' studios, like those of Bernar Venet and Christo and Jeanne-Claude. "I had to really understand what that artist was doing, and be able to explain it to people who didn't have an art vocabulary but had the sensitivity and wanted to learn," she says. There were plenty of rich people among the crowd. As Guggenheim tells it, a certain woman hadjust bought an apartment in UN Plaza, hired Angelo Donghia, the famous designer of the day, to decorate it, and now she wanted paintings—could Guggenheim help her? "I advised them to buy a Lichtenstein painting, a Donald Judd sculpture, and several other things. And at the end of the year, I looked at my balance sheet and I saw I had made a lot more money helping this woman buy art for her apartment than I did on many, many, many tours. But I'd never met anyone who could afford to have a painting before."

When she turned this into a business in 1981—Barbara Guggenheim Associates (BGA)—she was the only one doing work of that kind; there were other advisers out there, but they worked for museums. New galleries were exploding—"the Lower East Side became the hot spot," recalls Guggenheim, who'd feed their business with a growing stream of clients. "Dealers, gallerists, and auction houseswere delighted to see me bringing new clients to their businesses." Uptown meanwhile, Impressionism was all the rage. "If you went into an apartment on Fifth Avenue, it would have French 18th-century furniture, puddling drapery, and French Impressionist paintings." She recalls the couple trying to replicate the look, telling her, " 'We like Renoir, but we can't afford it. What do we do?' So I introduced them to American Impressionism, and they went on and created one of the best collections of American Impressionism in the world. "

Twenty years before Carrie Bradshaw, Guggenheim was living a kind of Sex and the City life, attracting Mr. Bigs of the day, like Goldman Sachs partner and collector Arthur Altschul and collector Stuart Pivar. As she told Vanity Fair in 1993, "Iwas a single woman, and those were the people I was meeting. Who else was I supposed to sleep with?" To Pace Gallery founder Aime Glimcher, with whom she's done deals over the decades, her cerebral-ness was as alluring as her style. "She was very serious, " he says. "And the most important thing was that she was interested in the history of art. "

Word traveled to Hollywood about the sharp and fetching young woman. Through New York dealer Nicky Wyeth, the son of painter Andrew Wyeth, she met producer Ray Stark, who introduced her to Aaron and Candy Spelling, whose 56,000-square-foot house she helped adorn with Impressionist paintings. "She was, and is, a rainmaker," says Peyser. "She has an uncanny talent for finding the exact right piece for a particular client's taste. She will walk in a house with you and in about 10 minutes get a sense of what would make this collector happy and enrich their lives."

When a young Ovitz came to New York on business, he'd make the journey to SoHo with Guggenheim. "She introduced me to all the movements going on at the time," he says. The two hit it off and their relationship became "like brother and sister," says Ovitz. His stock in Hollywood was at its peak, and before long her Los Angeles client list became a Rolodex-worth of A-list operators: Spielberg, Cruise, Jeffrey Katzenberg, Don Simpson, agent Ron Meyer, producers Kathleen Kennedy and her husband Frank Marshall, who became friends. Ovitz introduced her to another power player, Hollywood superlawyer Bert Fields—the fearsome attorney who purportedly never lost a trial—whom she fell in love with and married in 1991. Because of Fields, Guggenheim relocated to Malibu and her social circle expanded to include Warren Beatty and Annette Bening, Mel Brooks and Anne Bancroft, and Dustin Hoffman. Joining forces, theybecame one of Los Angeles's It couples, posing for Vanity Fair in black tie on a Malibu beach. "With the most powerful people, she could hold her own," says Glimcher. "She was invited to everything."

In 1987 a 23-year-old Abigail Asher walked into her boldface life. Raised in London, Asher had gotten a BA in art history from the University of Manchester and was looking for work in the art world. A friend introduced the two. As it happened, Guggenheim's work was exploding in Los Angeles, and she needed someone to handle administrative affairs in New York. It seemed to be the start of something beautiful. Asher saw in Guggenheim someone who could be her mentor and took pride in the fact that this was a woman-led company in a world that was dominated by men. As for Guggenheim, she found in Asher someone she could rely on—and then some.

Asher diligently managed the company, and Guggenheim, true to her word, mentored her as an art adviser. Asher began cultivating her own relationships with dealers and collectors, bringing in two of the firm's biggest buyers. One of them, hedge fund manager and philanthropist Donald Sussman, recalls how the young woman's shrewdness was on display from the start. In 1990, aware of his interest in Surrealism, she called him to report that the communications and advertising firm Saatchi & Saatchi was in financial straits and had a spectacular Magritte they'd be keen to unload. "She and I flew overnight from Newark to London," Sussman recalls. "They brought the painting to the Concorde lounge. I brought with me a certified check. I handed them the check. She took the painting. I went back to New York. She brought it back to New York. And it was my first significant painting I ever bought." Years later, on one of the many trips that Asher and Sussman made to Art Basel, she spotted a Mark Bradford that took his breath away, and he wanted it. The dealer declined—he only wanted to sell it to a museum—but Asher persevered on Sussman's behalf, persuading the dealer that Sussman was a worthy collectorwithwhom the dealer should want to be in business. "I own it because Abigail is so highly regarded by these people," says Sussman. You might say she was turning into a young Barbara Guggenheim, but with East Coast financiers instead of celebrities.

Guggenheim was duly impressed and in 1995 offered to make Asher a co-owner of the business. But Asher turned her down. At the time, according to Guggenheim's complaint, Asher explained that it was because as a non-US citizen, she didn't want to be a business owner in the US. But she asked that her name be put on the door and that the name of the company be changed to Guggenheim Asher Associates (GAA), and Guggenheim agreed. The women made an oral agreement, in which they would split all proceeds 50-50, less the expenses.

But the pages of Asher's legal complaint, filed in July, paint a very different picture of the women's relationship, at least from Asher's perspective. Those early years were not some idyll between mentor and mentee. On the contrary, as the complaint reads, "As Guggenheim introduced Asher to the art world, Guggenheim exposed the troubled inner-workings of how she ran her life and work." We are told that Guggenheim (unmarried for the first few years) had sexual relationships with multiple dealers and collectors, and those relationships involved "sexual favors" and "kickbacks" pertaining to the business. No specific evidence to that effect is cited. A single incident is presented that illustrates what may have been a conflict of interest. In 1988, Guggenheim had procured a painting of the Pieta by William-Adolphe Bouguereau for her client Sylvester Stallone, and the seller was Pivar, her onetime paramour. Stallone later discovered that the painting had what he believed were slashes in it that had been restored. He sued her on the grounds that she had misrepresented the piece, and was acting for the benefit of her ex-boyfriend, not him. Guggenheim has said that the slashes were in fact just folds, as a result of having beenrolled at one point; it's unclear to what extent her prior relationship affected the deal. (The suit was later settled.)

"Guggenheim often tried to force these degrading values onto Asher," the complaint goes on to say. It chronicles how she tried to set Asher up on dates with older men whom she viewed as prospective clients; how on one occasion, she told Asher not to go to a client's house unless she was prepared to sleep with them; how on another occasion, when Guggenheim sent Asher to Los Angeles to help sell a Warhol, she told her to "wear leather and be provocative." Guggenheim, we are told, encouraged Asher to build a relationship with Jeffrey Epstein, "with whom Guggenheim and her sisterwere close," and that Epstein and his girlfriend Ghislaine Maxwell "were going to be a good source of'rich contacts. ' " (Asher's attorney, Luke Nikas, declined to answer when the alleged conversation took place; Epstein wasn't investigated until 2 005.) In response to these personal allegations, Guggenheim's attorney William Charon says, "Ms. Asher is obviously hoping to litigate in the press and not in the Court, thinking she has a better chance of applying public pressure on Ms. Guggenheim than actual legal pressure. Ms. Asher's legal claims are indeed meritless and her allegations are false and defamatory."

If what is claimed in her complaint is true, then it's possible that Asher felt like she was getting pimped out by her boss. It's also possible that she misread Guggenheim's intentions. Indeed, to Guggenheim's defenders, the essence of Asher's portrayal does not square with the woman they know. "I can't picture Barbara telling Abigail to go sleep with one of their clients," says Ovitz. "It's just not her. I've never heard anything like that out of her mouth. She's one of the most elegant, charming, intelligent women I've ever met." As for Guggenheim's suggestion about the leather? "It's beyond hilarious to anyone that knows Barb," says Peyser. "Barb's wardrobe is famously chic and conservative. I never saw her in anything but shades of black, white, and cream with necklines up to her collarbone."

After all Asher had been subjected to, according to Nikas, the real reason she turned down the 1995 offer to co-own the business was that she couldn't be so closely tied to Guggenheim. Yet she stayed—a peculiar decision, one might think, given all the unpleasantness she claims she was experiencing. "She's young, nine years out of college, still early in her career," says Nikas by way of explanation. "Her concern was that Barbara would disparage her if she quit, if she took clients, if she went somewhere else." No evidence from that time suggests Guggenheim would be inclined to disparage her, but "that was her perception," says Nikas. There was something else that would come to trap Asher. For all of her attention to detail, and obsession with dotting every i and crossing every t, she did not insist on anything in writing when it came to her partnership with Guggenheim.

Asher set about the newfound arrangement keeping her nose to the grindstone and working as independently from Guggenheim as she could, says her lawyer. As a result of her work with dealers in New York and London, "GAA's profits soared," says the complaint. As time went on and Guggenheim aged, Asher, it seems, began to perceive an imbalance, and it rankled her— she was doing the heavy lifting and bringing in the commissions, while Guggenheim was losing her mojo and constantly needed Asher to step in. As chronicled in the complaint, there was the time in 2005 when Guggenheim instructed Asher to come to LA to look at a Diego Rivera with a major Hollywood couple ("[I'm] not going to be good at discussing the Rivera with these clients, and you sound so much more articulate and I see how these clients respond listening to you," Guggenheim is quoted as saying); the time in Palm Desert, California, when she asked Asher to help sell a Rothko—she faked losing her voice because she was afraid to answer questions from the collector; the time when Guggenheim asked Asher to come to Los Angeles to see a certain Joan Mitchell painting on behalf of client Tom Cruise, because, as she told Asher, "I don't know what I am looking at."

As for Guggenheim's suggestion about THE LEATHER? "Its beyond HILARIOUS to anyone that knows Barb," says LA art adviser Patricia Peyser. "I never saw her in anything but necklines up to her collarbone.''

80. Guggenheim often tried to force these degrading values onto Asher. When Asher started working with Guggenheim (while Asher was still in her twenties), Guggenheim would set her up on dates with older men whom Guggenheim viewed as potential clients.

the universe, Guggenheim responded with belligerent threats. For example, in 2016, when Asher expressed that she was unhappy with Guggenheim's abusive attitude and conduct, Guggenheim dared Asher to hire a lawyer. Guggenheim reminded Asher that she was married to her "secret

weapon" and said she would "destroy" Asher in a legal battle and "drown her in legal bills.

According to Asher's filing, while she was busy doing Guggenheim'sjob, Guggenheim was indulging in a lavish lifestyle, expensing nonbusiness things like stays at luxury spas and Fields's travel. She also complained that "for Barbara Guggenheim, gossip, fame, and status are an obsession," an odd objection given that Asher went headfirst into a niche marked by high-status objects, celebrities, and heat-seekers. She cites as an example of this obsession Guggenheim's book Little-Known Facts About Well-Known People. Guggenheim plucks a copy from the coffee table at her apartment and flips through to show you its content—quaint illustrations and innocuous factoids about the likes of Gandhi, Winston Churchill, and Benjamin Franklin. "Because I'm so obsessed with fame," she says facetiously.

Then came Guggenheim's alleged demeaning and bullying behavior—like the time in Los Angeles with a potential celebrity client in 2019. Guggenheim, according to Asher's complaint, had made a comment about having googled the person beforehand. When an embarrassed Asher tried to change the subject, Guggenheim allegedly lashed out at her, claiming that Asher's first job was sweeping her floors. If Asher was getting bullied, she didn't speak about it to her friends. According to London-based art lawyer Pierre Valentin, who counts Asher as a friend, "I remember overhearing conversations between Abigail and Barbara.... I could hear Barbara screaming down the phone. Now, is that bullying? I don't know. I've heard shouting matches between the two. But it seemed to me at the time that it was their way of communicating."

On the occasions where Asher mustered the gumption to confront Guggenheim about her disapproval, Guggenheim would shut her down by making reference to her "secret weapon, " according to Asher. That would be her then husband, the fearsome Fields, whom Asher claims loomed over thenpartnership as a threatening presence. Guggenheim, according to the complaint, let her know that Fields believed that Guggenheim had been too generous with her. But mainly, it was the use of the term "secret weapon" that Asher took as a threat. The claim is dubious to Peyser, who points out that Guggenheim referred to Fields as "my secret weapon" all the time, as an affectionate joke—he was the man who'd always have her back. "You would only interpret Barbara calling Bert her secret weapon as a threat if you didn't know Barb well, or you completely lack a sense of humor," she says.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 91

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 71

And then, from 2016 to 2022, "Guggenheim's bizarre behavior reached new heights," reads the complaint, which illustrates the charge through a series of incomprehensible emails written by Guggenheim, along the lines of this: "Arrange please . I was supposed to see a Moran at qnaieds but didntww I thought it assez for the sec house and you could go see it first. There's. One outside the Mincol bedroom qnd Becquse if spirants . The park d'user' ans staged. I thought some tradiiro aeeican art could be good Also he likes star war stuff.' Ahah about Gursky and Vija Celmins qnd so."

"Barbara's a terrible texter," admits Peyser. "But what we don't understand about that—and I've known this because of 20 years of reading her miserable texts—is that she's in constant motion. She's in the back seat of a taxi. She's running to catch a plane. She's prepping notes for her next lecture. She's having dinner with clients, flying to Chicago or something for some random dinner that she feels is going to be productive for her business." It's also possible that Guggenheim was just showing signs of age. Indeed, Asher's complaint sees fit to note her "mental decline."

In 2022 the issues that had been brewing came to a head. It was an emotionally turbulent time for Guggenheim. Fields, who'd been ill for several years, died that summer; she'd started seeing Patricof, and the two were planning on getting married. Asher had had it with the imbalance of their work output. With the help of Robert Mandeltort—an outside accountant who'd worked at the company since the '90s, now acting as "mediator"—Asher proposed revising the old oral agreement. For 3 0 years they had split the revenue equally. Now, she suggested, they would separate their commissions—into Guggenheim's bucket and Asher's bucket—with each drawing individual revenue from their individual sales. Any commission that involved them both would go to the old, combined pool.

"I looked at my balance sheet and I saw I had made a lot more money helping this woman buy art for her apartment than I did on many, many, many tours. But I'd never met anyone who could afford to have a painting before."

Here we get to the crux of the dispute: Asher contends Guggenheim verbally agreed to the proposal, and that they even hammered out details about pay structures. According to Nikas, once the agreementwas made, Guggenheim was satisfied and invited Asher to her upcoming wedding. Charron, Guggenheim's lawyer, disputes this account. "BGA's position is that so-called mediation was a charade designed to extract lopsided terms in Ms. Asher's favor, which failed and never resulted in Ms. Asher's compensation terms changing. Ms. Asher can point to no writing between her and Ms. Guggenheim ever confirming any change in terms." Nikas counters that there had never been a written agreement regarding the business in the first place. "In fact, Guggenheim's complaint is premised on an oral agreement between the parties," he says. Whatever the case, when Asher started her own Asher Art Group in March 2023, she claims she was following through exactly with what had been agreed upon, while Guggenheim experienced it as a betrayal—as Asher, in effect, stealing part of the company Guggenheim had built over 40 years.

In April 2024 Guggenheim fired Asher and months later filed a complaint, alleging that Asher had "secretly launched her own competitive art advisory business while she was a fiduciary of BGA, " and that Asher had used company funds for personal expenses. The suit also names Mandeltort and Asher's assistant Jessica Lewis for being liable in aiding and abetting Asher. (Through their attorneys, Mandeltort and Lewis declined to comment.) "It was under the radar," Guggenheim says of her complaint. It had "no mud-slinging, no lying. It had to be done. I was not happy. I wasn't gleefully doing it. " The personal-expense piece emerges as fairly negligible—especially in light of Guggenheim's own alleged use of company funds. The boldness was in the amount she was asking from Asher: $20.5 million.

As Nikas explains, that figure is based on potential money that Asher could make buying and selling for her current clients, like Sussman. "It's outrageous," says Sussman of Guggenheim's position, acknowledging that he doesn't know the terms of their arrangement. "I've met Barbara three times. She's never advised me about anything." He and others, from both sides, were kept in the dark about the tensions brewing. "I've had a lot of intimate conversations with her," Ovitz says. "I will tell you, they weren't about Abigail," he says. "When Barbara told me they had a problem, I said, well, just settle it. You don't want to get into these issues in the press. You just don't want to do that." Yet, here we are.

In fact, discussions were had between the sides about settling. According to Nikas, they were productive—he and Asher believed Guggenheim was acting in good faith. All that changed, he says, when they learned of an article that ARTnews was planning, which they believed Guggenheim was participating in and suspected would be a hit piece aimed at destroying Asher's reputation. At that point, Asher's team pounced and filed thensuit. An ARTnews story came out, but it wasn't a hit job.

Even among Asher's defenders, there's a lingering uneasiness about the harsh, personal tone of the complaint, which feels incongruous with the woman they know. "It was a little sordid, but who am I to judge?" says Valentin. But he insists, "For her, this has been really, really difficult. And I believe that, because she's not that sort of person,

but of course she has to defend herself. And New York litigators are known for being very aggressive, and unfortunately, she has to go along with whatever she's being told is the best strategy, which is to counterattack. But I know, because I know Abigail very well, that it's not her style."

Guggenheim predicts that Asher's nuclear approach will backfire. "I think she's tarnishing her own reputation more because it's so crazy." In September her attorney filed a motion to dismiss Asher's "outrageously trashy" allegations on the grounds that its sole intention was to shame Guggenheim to the point where she'd negotiate a settlement. Now ratcheting up the language on her side, the motion to dismiss added that, "Asher is a liar, a fraudster, a bully, and a thief." (To which Nikas responds, "Guggenheim started this dispute by filing her meritless complaint in an effort to bully Asher into an extortionate settlement.")

For now, Guggenheim is projecting confidence. She shares that she was just lecturing in Newport, Rhode Island, and that in the past two weeks she's nabbed two new clients. But looking ahead at months of litigation, it's hard to see any winners. "You'll see who keeps the clients and who is going to earn a living and who isn't," says Ovitz. "But at Barbara's stage of her life, and Abigail's—they're not spring chickens, and this is not a good time for this in their lives, either of them."

The battle has elicited a touch of schadenfreude and an opportunity for score settling in some quarters. As controversial LA collector Stefan Simchowitz puts it, the case reveals "the broader rot in the system," where all the kissy-kissy politeness amounts to a "veil of bullshit." As a case in point, he reports how Guggenheim recently flattered him by inviting him as her date to a dinner for MOCA. "She was driving a Rolls. Very elegant white pants. So nice to see someone of that age just so beautiful and elegant. I love her for that." He turned around only to learn that she was telling artists not to do business with him. "It's quite ironic," he says, acknowledging that he doesn't know the details of the complaints. " 'He's the bogeyman.' No, I'm not the bogeyman. It's the well-dressed lady in the nice white suit. "

So the knives are out. Right now, rather than settle, both women seem ready to spend a fortune on the pleasures of trying to publicly crush one's opponent in a courtroom. It's the kind of scorched-earth divorce that can only happen between a couple where once upon a time there was a great love.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now