Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

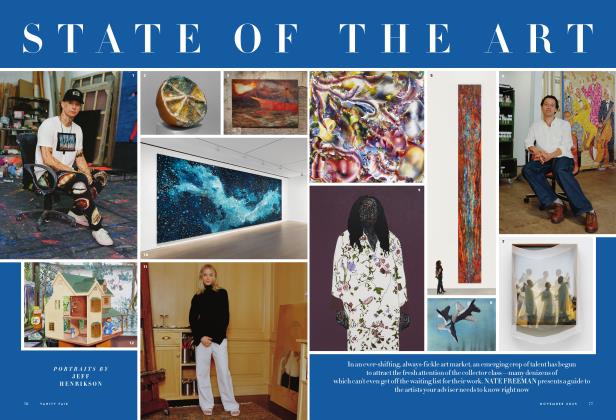

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSTUDIO VISIT: MUSE AND MAKER

The painter Kate Capshaw, known for her intimate likenesses, could hardly say no when the National Portrait Gallery commissioned one of Steven Spielberg, her husband of more than 30 years

In 2016, seven years after beginning her visual art studies, Kate Capshaw began working with youth organizations to paint the portraits of unhoused young people. She arrived at shelters with food and water, listening to them describe their lives as she worked. The resulting series, "Unaccompanied," hung at the Hope Center in Los Angeles. At the National Portrait Gallery, director Kim Sajet and curator Dorothy Moss took notice. She reportedly urged Capshaw to apply for a portraiture award, and after she placed as a finalist, the NPG temporarily hosted three works from "Unaccompanied." (In May, amid sweeping changes to the Smithsonian, which houses the NPG, President Trump posted to social media that he was ''terminating" Sajet's employment due to, he claimed, her support of DEI. Sajet stepped down from her position in June.)

Three years ago, when it came time to commission a portrait of filmmaker Steven Spielberg for the NPG, Capshaw was an obvious choice. Yes, she had an undeniable knack for portraiture, but Capshaw also had special insight into the director of Saving Private Ryan, Schindler's List, and Jaws. Before she was an artist, Capshaw had acted in Spielberg's Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. They have also been married for more than three decades.

"I was very moved," Capshaw says when I meet her this summer. "I felt the honor. I felt the heft. I know this man, and I know how large he is, and I also know how very intimate he is." She set out to capture Spielberg the person rather than Spielberg the phenomenon. Instead of leaning into the iconic image of Spielberg as a swashbuckling New Hollywood icon or a box-office-slaying hero, she opted for her signature black background and used as the source material an image of a softly smiling Steven at their breakfast nook: Steven the partner with whom she's raised multiple kids, made a life.

"I wasn't going to put a camera in the portrait, and I wasn't going to put him on a director's chair, and he wasn't going to wear a baseball cap," she says. "I wasn't going to have ET flying in." And yet the portrait had to somehow convey her husband's monumental contribution to American culture. Then, eureka: She could project her husband's work directly onto the canvas.

And not, say, Leo in Catch Me If You Can—she wanted clips that were personal. So she asked her husband if she could root through the never-beforeseen early work that the budding auteur shot when he was a precocious teenager.

"It was like I had just found the amber in Jurassic Park, and I realized there was DNA in it," she says. "I discovered that there were archival films from when he was 18. Come on. Treasure chest."

For film nerds, this is a revelation. There's even footage from his legendary lost sci-fi film, Firelight—Capshaw uses a scene that Spielberg copied in his autobiographical film, The Fabelmans. Watching the proto-Spielberg artifacts, it's shocking how the filmmaking prefigures his mature masterpieces. "Sugarland is there, Indiana Jones is there, West Side Story is there," Capshaw says. "All of the war movies are there."

After Spielberg is honored at the Portrait of a Nation Gala in November, the work will enter the permanent collection, complete with the film projection. "I was given the task of painting a portrait of this man who I couldn't love more, but it was going into an institution that would own it forever," she says. "I've been given this story to write. I'd better damn well write it great."

NATE FREEMAN

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now