Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM

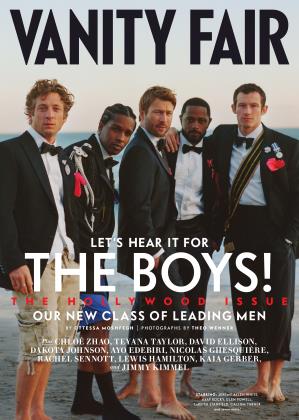

Hollywood knows AI is a profound technology bound to be transformative, and also bound to replace humans. It's all anyone can talk about in private, at parties, on location. With the town on edge, TOM DOTAN plumbs the industry's anxiety—and hope

TOM DOTAN

In early October the director Timur Bekmambetov, known for films like Wanted, starring Angelina Jolie, or perhaps Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, hosted a dinner party to talk aboutwhat might aswellbe a sci-fi logline and the only thing anyone in Hollywood can talk about at all: AI.

Bekmambetov's house in the Los Feliz hills was such an apt setting, it was almost too on the nose. Designed by Walt Disney with architect Frank Crowhurst in the 1930s—a storybook revival manor, ivy climbing across its facade and turret—the whole place stood, like the industry itself, in a state of beautiful slow decay. As if Norma Desmond had holed up in Sleeping Beauty's castle. Before dinner a Disney historian led Bekmambetov's guests on a tour of the home—through the mansion's grand foyer, up a spiral staircase with handrails that certainly seemed not up to code, and finally into Disney's original screening room, where for almost 20 years he was said to review studio dailies for movies like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Fantasia. Tonight a film was already cued up: a teaser for a horror flick made by Bekmambetov's daughter, set on the property itself. In this movie the house has long been abandoned after a party decades earlier, when Disney's rejected concept art springs to life and turns against the moviemaker and his guests.

Save the opening scene, the teaser's effects were all done using AI, training the software on real images of Walt Disney in the public domain and inputting prompts like "Disney looking at the camera in fear." It took Bekmambetov's daughter a month to make it.

The party guests that evening were a combination of tech and media executives, and as is so often the case when emissaries of Northern and Southern California summit in one place or another, the sides didn't naturally mix. Early on, the leaders of a few generative AI start-ups mingled near the entrance. Later, a figure who bridges the gap brought some charisma to the affair: Bryn Mooser, in a brown field jacket and tightly cropped graying hair, looking more like a war correspondent than either the filmmaker or the digital media entrepreneur that he is. He introduced himself around, then quickly found a familiar face.

"Natasha, we're having a smoke," Mooser said, motioning to the actor Natasha Lyonne, wearing combat boots, sheer hose, and a velvet jacket, all black, naturally. (They're business partners and had been dating for a couple of years, though they recently broke things off.) They excused themselves from the tech crowd.

Later, Mooser tells me he was annoyed with both those who call AI a tool only for slop and those churning out the slop themselves. There's a personal edge to it. A fifth-generation Angeleno, he's watched Hollywood hollow out as its business slows and productions chase tax credits out of state or overseas. The decline has settled over a region already battered by disasters—natural (wildfires) and man-made (ICE raids).

Visual effects have largely been farmed out to shops around the world. The sooner Hollywood embraces AI, the more it can turn it into a homegrown industry with local jobs, he believes.

Eventually the group convened to sit for dinner in Disney's dining room. Over servings of plov, morkovcha, and other dishes common in Uzbekistan, where Bekmambetov began his theater and film career, they got to the heart of the matter: the rise of the machines and just how much they will destroy Hollywood—or move it forward. The one thing everyone could agree on, can see forward on, is that AI isn't going back in the bottle.

Those who view the coming world of AI video through the algorithm's rose-colored lens see a tool that could forever change the way movies look—like animation post-Pixar. Or one that hums quietly in the background, making visual effects and preproduction faster and cheaper. Or, more radically, a worldwide democratizing force that hands the means of production to anyone with a story to tell.

Eitherway, in a war for diminishing attention spans, people like Black Swan director Darren Aronofsky have embraced AI almost as a kind of realpolitik. If the technology is going to arm the tech platforms with addictive, disposable content, Hollywood has little choice but to use it, and hopefully for good.

"You can sort of be afraid of it and attempt to fight it," Aronofsky says. "Or you could try to figure out how to use it to tell different types of stories."

There's also a strong resistance to that vision of the future. Many in Hollywood don't want to give an inch to the technology on either side of the camera, fearing its impact on jobs, or on creativity itself. Generative AI is by its very nature derivative, and bringing it into the process feels like surrender.

Some directors and producers have suggested they want the industry to embrace the tech, but are terrified of being publicly cast as creative-class traitors. At least two dozen of some of Hollywood's best-known creatives did not respond to questions about their own usage and feelings, or the industry's trajectory. One major producer, an optimist here, wouldn't even speak on the record about the path toward harnessing it, for fear of blowback.

The fact is, no one at the table or across the industry really knows how or when, or even whether, AI will become the transformative technology its proponents and alarmists make it out to be. The movie business has always reinvented itself with each new technology—from talkies to Technicolor to CGI—but this one, tangled up in lawsuits and bad vibes, feels different. That has created an oxymoronic stance from an ailing Hollywood, where many studios are restricting directors from using many generative AI tools while quietly hoping they will eventually feel free to open the floodgates and save a lot of money.

"A STORM S COMING, Y'KNOW?"

It had been a heavy week. OpenAI had released the second generation of its copyright-skirting video app Sora. "Tilly Norwood," an Ai-generated "actor," was supposedly being fought over for agency representation, and the prospect seemed nigh of Hollywood's creative output being forced down the feed tube of Silicon Valley's Cuisinart. (The CEO ofParticle6, Norwood's creator, later tells me that Norwood had not been intended as a PR stunt, and that the company was "quite taken aback" by the response.) Bekmambetov's dinner crowd was a fairly optimistic group, partly owing to the fact that most of them had a stake in AI succeeding as a bigger part of the creative process. Lyonne and Mooser cofounded the AI studio Asteria, which aims to safely incorporate the technology into their films. Executives from Lionsgate and Blumhouse work for outfits that are either leaning into partnerships with tech companies or actively licensing their IP to help build better AI tools. The tech CEOs from companies like Stability AI and Luma AI are selling the tools to bring AI video to life.

Mooser suggested that, given the talking points coming out of the Trump administration around allowing AI companies to train their models freely on copyrighted materials, most would get by with just a wrist slap. Lyonne pushed back.

"Things don't have to be so negative, Bryn," she said, clinging to the possibility that the courts could side with the industry in the case of an all-out war over IP.

The conversation soon turned to less fraught topics. Amit Jain, the CEO ofLuma AI, was excited about the comet C/2025 A6 that was streaking past Mars and would soon be visible in the October night skies.

A few days later I recount the party to the filmmaker David Ayer. He says it allfeels very familiar. "If Iwas gonna take a general temperature, it's like a storm's coming, y'know?" Ayer is a traditionalist, if not quite a Luddite, who still bangs out his treatments on a typewriter. The man behind gritty police dramas like Training Day is on the Paramount lot, in postproduction for an upcoming adventure movie starring Brad Pitt.

"You're out in the prairie and you see the dark clouds and the wind's starting to pick up, and you don't know what it is, and you don't know how bad it's gonna be," he continues, "but you know things are gonna be different."

"There's just nothing comparable to it—certainly not in the last 50 years," says Jeffrey Katzenberg, a persistent optimist. These tools, he says, "have the ability to assist in every single scintilla of creation, whether it's around words, whether it's around previsualization, whether it's around the effects, whether it's around voice, language, character."

WILL SMITH S SPAGHETTI

AI writing tools have already worked their way into the process. Ayer imagines for some it's like the bottle of vodka on the desk at lunch that makes the job easier to get through. David Goyer, the former showrunner for the Apple TV sci-fi series Foundation, says he typically has Perplexity, a popular AI tool, open in a window alongside his script—mostly for quick research. He'll use it when he's stuck for ideas, like what kind of blue-collar job a character in the 1960s might have.

He's taken it further than that at times. Once he used Perplexity to trim a three-minute scene he'd written for the show down to two minutes. (The Writers Guild in its 2023 memorandum of agreement allows writers to use generative AI tools as long as the company consents.)

"As opposed to me spending another hour rewriting the scene, it kicked out five versions that were not perfect, but close," Goyer says. "It turned an hour's work into five minutes' worth of work. " As anyone who putters around with ChatGPT can attest, the tech's generic flow, cheerful tone, and bizarre reliance on em dashes is better suited for cheating on a college essay than producing something you'd pay to read. The improvements in writing tools, which are trained on existing creative work, seem to have leveled off over the past year.

AI is getting used in other creative settings. Goyer says a friend of his was in Atlanta directing a show and was a few days behind schedule when an executive at the studio gave a list of shots generated by AI to speed the process and provide the bare minimum needed to cover the scene.

It was a depressing blow, Goyer thought, to the idea of an author's voice. He also suspects the network notes on his scripts are, more often than not, written by a chatbot.

"It's literally some assistants just feeding the script in, and then you're getting these very generic notes turned out and it's saving them the bother of having to write notes," Goyer says. "In some cases you can even tell what model was used." [Editor's note: for a little fun on this point, see "Deus ex Chatbot" on page 62.]

The capabilities of AI video have leapt in the last year. In 2023 a viral clip of "Will Smith" eating spaghetti made the actor look bug-eyed and disfigured as he maniacally shoved noodles into his mouth. The newer iteration, created with the latest version of Google's Veo 3 tool, shows unnerving polish: A convincing likeness slurps the pasta with steam rising off the plate and even says in Smith's voice, "I can't get enough of this. " (Actual Will Smith did not respond to Vanity Fair's inquiry.)

Storyboarding and other pre-visualization processes are almost certainly never returning to the pre-AI era. That may not get the same hype and provocation of a Tilly Norwood, but its effect on a production is profound. AI can visualize the way an actor looks in a variety of costumes long before they arrive on set, avoiding wasted production hours.

One executive at a major independent studio described making a full AI Him as a "fool's errand" because of ATs inability to convey the genuine emotion and humanity of great acting. Worse, it still can't deliver the control and continuity that directors, many of them self-confessed artistic control freaks, demand. But for the preand postproduction elements, there's much less dissent.

"There's no one who's been in sort of a moral way saying, T refuse to see any costume variation possibilities,' " the executive says.

That behind-the-scenes work is what companies like Stability AI are selling. Its CEO, Prem Akkaraju, is skeptical that AI video will be precise enough in the near term to be worthy of pixels onscreen. So rather than replace the camera, he's placing his bets on transforming the postproduction process.

"Everything to the left and right of that, which is time-consuming, which is super costly, which is really not that creative and is really the needlepoint part of content creation," says Akkaraju. "That's the area that we really are focused on."

'THEY'VE GOT THE UNIONS TIED AROUND THEIR NECK''

When the Hollywoodwriterswent on strike in 2023, they fought a battle over what it means to be a creator in the age of algorithms. They won concessions from the studios that, yes, only humans can be credited as the writer on a project.

The actors union, SAG-AFTRA, which stood in solidarity with the writers, has been fighting a battle chiefly around consent. Their fear isn't so much that AI will replace actors altogether, but that itwill be used to make them say or do things without permission. The union's executive director, Duncan Crabtree-Ireland, says he experienced this firsthand when, during the contract vote, someone created a deepfake of him saying false things about the contract and urging members to vote against it.

"You can sort of be afraid of it and attempt to fight it," says Darren Aronofsky. "Or you could try to figure out how to use it to tell different types of stories."

"One huge win was just the fact that labor, the Writers Guild and us and other unions as well, were really speaking with one voice and sharing in that solidarity a message that abusive use of AI is not okay," Crabtree-Ireland says. "It's not okay with the writers, not okay with actors, not okay with any of us. And we are going to take a stand, even if it's at peril to our own livelihoods."

The unions' control over the process is profound in Hollywood. Even Netflix, which brought a tech ethos to the industry and ripped up the script around so many aspects of how actors and producers are compensated, has been on the defensive.

"Netflix was once the ultimate outsider company in the Hollywood it was reinventing. Now they're very much insiders, and how good are insiders at reinventing themselves?" says one former Netflix executive, adding, "They are the establishment now. And like the rest of Hollywood, they've got the unions tied around their neck. " (Netflix did not respond to a request for comment.)

Given the legal concerns around AI, Bekmambetov found out that even making a film about AI and for a tech giant doesn't fly in today's industry. In Mercy, his upcoming release for Amazon, Chris Pratt plays a suspect in a murder trial overseen by an AI judge, played by Rebecca Ferguson. Despite the fact that it's being financed by a company that may be one of the largest investors in AI in the world, executives apparently gave him a strict "no AI" policy. (Amazon did not respond to a request for comment.)

"They didn't want to have any AI anything—voices, images, visual effects, nothing," Bekmambetov says. "And I understood it. It was not wrong."

GOOD FOR THE GANDER?

Even as Hollywood learns to absorb the technology, the AI companies' seemingly burn-the-boats approach to product launches has been, at best, grating.

Nowhere was that clearer than with OpenAI's release of the Sora app, which initially required rights holders to opt out of appearing in its clips. The result was a chaotic few days when anyone could easily generate videos featuring South Park characters or Pokémon. OpenAI defended the training process as allowed under fair use. An executive said it gave the freedom to generate likenesses as a way to give people the ability to create without too many guardrails. Also, because every other video app was doing it too.

The move infuriated much of the industry. Creative Artists Agency (CAA) issued a statement saying the app "exposes our clients and their intellectual property to significant risk." A few days after launch, the company changed its policy to an opt-in, dramatically cutting the number of Ai-generated likenesses. No matter, Sora flew to the top of the App Store.

"We're engaging directly with studios and rights holders, listening to feedback, and learning from how people are using Sora 2," said Varun Shetty, VP of Media Partnerships for OpenAI. "We're removing generated characters from Sora's public feed and will be rolling out updates that give rights holders more control over their characters and how fans can create with them."

It was a flashback to the rise of YouTube, which also got traction by showing a lax attitude to copyrighted content and was sued by Viacom in 2007. The lawsuit dragged on for nearly a decade. While YouTube and Viacom eventually settled in 2014, YouTube prevailed in key interim rulings. Viacom, now Paramount, was acquired this year for some $8 billion, or less than what YouTube now makes in a quarter.

To many unions, the Sora affair reeked of Silicon Valley hypocrisy—"Move fast and break things" for thee, not for me.

"I think it's ironic that the very companies who are taking everyone's intellectual property to train and fuel their models themselves rely heavily on intellectual property laws to try and protect their algorithms," Crabtree-Ireland says. "It's interesting that what's good for the goose isn't good for the gander."

The actor Joseph Gordon-Levitt laid out the contradiction in even starker terms: "The models they make are 100 percent useless, they have zero value at all, they don't do anything without the human-produced content and data."

The Inception star, who founded an online community, HitRecord, that encourages users to upload and share creative work, has argued that there needs to be a system by which AI companies share revenue with the creators whose work they use to train their models. (Gordon-Levitt's wife, Tasha McCauley, is a tech entrepreneur and former board member at OpenAI.)

Also staunchly rejecting the fair-use argument are Lyonne and Mooser. Thenstudio, Asteria, partnered with AI company Moonvalley to create a video model that is trained only on licensed material. They pitch Marey as the first "commercially safe" video model.

Asteria is currently developing an AI film, Uncanny Valley, which Lyonne cocreated with actor Brit Marling and technofuturist philosopher Jaron Lanier. It combines traditional techniques with AI generated scenes that producers say would've been impossible on their budget without Marey. Other hybrid studios are emerging, like Promise, which is funded by a Silicon ValleyHollywood alliance that includes Andreessen Horowitz, Google, and Peter Chernin's investment group.

Lyonne and Mooser have taken heat for publicly leaning into AL Over the summer the actor told New York magazine that her neighbor the late director David Lynch described AI as neither good nor bad, just another tool for directors. Film purists accused her of leveraging the beloved director's cred to push her company. Mooser maintains to me that Lyonne's conversation with Lynch did happen. The criticism clearly stung Lyonne, who was hesitant to talk: "I feel like you're going to pull-quote me into a house of darkness. " She only talked to VF, she says, because Gordon-Levitt, a friend, told her that he had.

The accusations that Lyonne had become a shill for the algorithm, which briefly led to her comments becoming a meme on X, were largely unfair. Spending even a few minutes with her, an indie darling since 1998's Slums of Beverly Hills, reveals Lyonne to be a genuine and voluble cinephile. She meanders into film obscura like the 1932 pre-Code movie Call Her Savage, starring silent film star Clara Bow. ("Oh, man, is she overacting in the scene with the Great Dane.") Lyonne found the tech companies dismayingly derivative. She pointed to a viral trend earlier this year, when people fed their family photos into ChatGPT to remake them in the style of anime legend Hayao Miyazaki.

"I don't think it's funny. I don't think it's charming, and I think pretty much anything is funny," Lyonne says. "I just actually find it like, you know, just a bummer."

Much like Gordon-Levitt, Lyonne's issue is with data scraping. She applauded the Disney, Universal, and Warner Bros. Discovery lawsuits against generative AI company Midjourney (which has pushed back by claiming fair use). Better the tech train only on the limited and licensed data available, even if it means it would create a less capable model."I love the idea ofwhat this tech would produce without actually knowing any of that information," she says. "You'd have to train it quite differently.... I'm not opposed to things that have nine fingers, for example. Maybe that's what this genre wants to look like."

CONTINUED ON PAGE 176

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 126

As for the haters, Mooser divides the anti-AI sentiments into two groups: the top echelon of Hollywood who are worried about their likeness being replicated by the tools and a younger group of film traditionalists.

He finds the first group selfish—they'll be fine no matter what. It's that latter group, the oneswho piled on him and Lyonne, that he seems to have the least patience for.

"Is Hollywood working for you? Are you working right now? Are your friends working? Does everybody have jobs? And it's working out awesome for everybody?" Mooser says, his voice gaining in frustration. "Because it's not."

"This is your shot and you've got the advantage," he went on. "So why not at least be open-minded to what about it could be helpful rather than just b eing critical online. "

A DISTINCT GENRE

So just how many jobs will be lost?

Goyer says his VFX supervisor predicted that the budget for Foundation would drop by a quarter in the next year or two as the quality of the tools increased. "You're not going to need 500 VFX artists. You might need 200 instead."

Katzenberg has gone even further, suggesting that in the near future AI will do some 90 percent of the labor for an animated film.

The speed at which the quality of the tools is increasing has astonished some producers. In Martin Scorsese's 2019 film The Irishman, a 76-year-old Robert De Niro was de-aged using a three-camera rig and Al-powered software to make him look like he was in his 2 0s. Jane Rosenthal, one of the film's producers, said it was a painstaking process that required retakes and meticulous direction.

"Marty would say, 'Okay, we have to do that again, because you're acting like you were 40 but you got up like you were 70," she recalls. With the tech she's seen only six years later, Scorsese wouldn't have needed to give the same kind of notes.

Rosenthal has been one of the bigger advocates for embracing AI in film. "If you want to talk about it, then talk with knowledge, then talk with an understanding," she says. In the past couple years, at the Tribeca Film Festival, which she cofounded with De Niro, she launched an AI film tract. It's produced in partnership with OpenAI.

She saw firsthand how high passions run when it comes to even discussing the issue. In 2024, when the festival hosted an AI panel with Sora, they had to ratchet up security, she says. Whether or not AI as a technology or a definable genre can overcome that label comes down to storytelling, says Aronofsky. The director launched a company, Primordial Soup, that partners with Google DeepMind to integrate AI in filmmaking. The company's unofficial motto is "Make soup, not slop."

"What's coming out of these machines now looks as good as anything Hollywood produces, but it's really just for a moment. It's for the eight seconds or the nine seconds that it exists, and it doesn't stick in people's heads," Aronofsky says. "The race is on to figure out how to breathe emotion into that slop so that you can link shots together to start to tell stories."

But even framing AI communities as a training ground for future mainstream filmmakers misses the point. The winners of AI film festivals are often people who come in knowing almost nothing, says VFX artist Ben Grossmann. A past judge at festivals, he's been struck by how many of the standout projects are made by amateurs with tiny crews.

"Igo talk to the filmmakers: So how many movies have you made before? 'None.' What did you go to school for? 'Not this.' How many of you worked on it? 'Um, me, him, and my buddy over there.' How long did it take you to do? 'Well, we started on Monday and by the following Friday we were done. ' "

For years Grossmann was a visual effects supervisor for directors like Scorsese, J J. Abrams, and Jon Favreau, and he won an Oscar for his work on Hugo—a feature-length love letter about the technology of making movies. Then Grossmann quit.

In film, "we're just doing the same thing now," he realized. "The innovation is gone, the new is gone, the creatives want to create cool stuff, but studios just wanted to make it cheaper."

He's since launched an immersive experience company, Magnopus, that he hopes will create a new genre of storytelling—one that combines the immersiveness of video games with the intimate storytelling of movies. AI, he hopes, comes to mean developing a distinct genre.

"A lot of focus right now for Hollywood is on how do we use it to make the old thing cheaper?" Grossmann says. "But I think the most interesting opportunity is how we use the new thing to make something new."

Bekmambetov believes there will always be a world of movies devoid of AI. A genre for traditionalists. "Like opera. It will be very, very valuable. Handmade. Organic."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now