Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMIDCENTURY MAISON

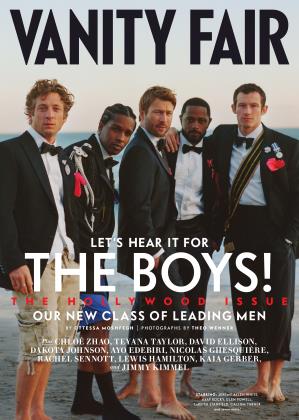

For years, Nicolas Ghesquière had one very special West Hollywood house on his mood board. PAUL GOLDBERGER tours the property—newly restored by the designer and his partner, Drew Kuhse—that is now the couple's American home base

PAUL GOLDBERGER

When you talk to Nicolas Ghesquiere, who has headed women's design at Louis Vuitton since 2013, you realize his secret weapon—the part of his persona that allows him to withstand the pressure of producing major collections throughout the year under the most intense public scrutiny—is that he feels as much passion for the act of connecting fashion to culture as he does for the draping of fabric. For Ghesquiere, fashion has never existed in a vacuum. His designs deftly blend traditional elements of Louis Vuitton like trunk hardware and the quatrefoil shape with references to futurism, pop culture, Japanese anime, science fiction, and modern architecture.

Since 2014, Ghesquiere had gazed at an image of a house in West Hollywood by John Lautner, the Frank Lloyd Wright disciple whose designs have now become as celebrated a part of midcentury modern culture in Southern California as those of Richard Neutra or Craig Ellwood. Ghesquiere had never been to the Wolff house, which was built in 1961 for Marco Wolff, a concert pianist and interior designer, and at that point barely knew Los Angeles. But the moment he came across the picture, he responded to the intensity of the house, a tightly wound composition of stone, wood, and glass perched on a narrow site high in the Hollywood Hills. Every Lautner house has considerable panache, not to say flamboyance; within the architect's striking shapes, there is a kind of explosion of space, and to move through it is to feel a sense of drama, brilliantly contained and controlled.

We could tell the long, rambling history of the Wolff house and how it went through several owners and how, like so many other classic modern houses in Los Angeles, it was treated with indifference for years before it was sold to Joachim Ronning and Amanda Hearst Ronning, who renovated it. But it makes much more sense to jump to the end of the story, which you can probably guess: The house now belongs to Ghesquiere and his partner, Drew Kuhse, who never expected to see it, let alone own it. But in 2022, after spending more time in Southern California—where Kuhse, a communications and branding consultant, grew up—including chunks of the pandemic isolated with him in rented quarters in Malibu, "we decided to get a house in Los Angeles," Ghesquiere tells me. "I had been carrying around that image of the Wolff house in my iPad for years and sent it to my agent to show her the kind of house I wanted—a landmark modern house that I could be responsible for."

"When we leave it to go back to Paris, it feels like saying goodbye to a person you love.

He intended the picture to make it clear that he and Kuhse were prepared to take on the challenge of some other midcentury architectural gem—strong, one of a kind, perhaps crying out for new owners who would carefully restore it. The picture was not supposed to serve as a shopping list, and anyway, Ghesquiere's real estate agent had already told him that so far as she knew, its owners were happily ensconced in the house and had no intention of selling. She would look, she said, for something similar, and Ghesquiere and Kuhse prepared themselves for a long wait.

Thatwasin October 2022. While Ghesquiere and Kuhse were on their Christmas holiday trip to French Polynesia, they heard from the broker that the Ronnings were relocating to Europe and would lease the house, and might consider selling it. Ghesquiere quickly changed his travel plans to go through Los Angeles on his way back to Paris to see it in person, and before long he made a private, off-market deal, at a figure reported to be $ 11 million, to buy the house. It was never officially listed for sale.

Ghesquiere had fallen in love with California modernism a few years before he and Kuhse met in 2020, when he visited one of the formative modern houses of Los Angeles, the architect Rudolph Schindler's house in West Hollywood from 1922. The Schindler house, a casual structure of tilted slabs of concrete, redwood, glass, and sliding canvas panels that the architect Charles Moore once called "a Bohemian shack," blurred the distinction between inside and outside. Ghesquiere was blown away. Like Schindler himself, who had come from Vienna a century earlier to work for Wright, Ghesquiere was a European who thought he had arrived in paradise, to a place open to every kind of experimentation.

From there it was not a great leap to John Lautner, a Michigan-born architect who, like Schindler, started as an apprentice to Wright. Lautner was sent to Los Angeles to supervise the construction of one of Wright's houses and never left. Lautner's work, too, celebrated the openness and ease he believed Southern California represented and seemed both to echo Wright's designs and to move beyond them into a kind of space-age modernism. The first Lautner house Ghesquiere saw was one of the architect's most memorable and certainly his largest: the vast concrete airship of a house the architect built in Palm Springs in 1979 for the comedian Bob Hope and his wife, Dolores.

For several years Ghesquiere had been showing Louis Vuitton's cruise collections in notable architectural locations around the world and scouting them himself. "I wanted to do a show in California, and I had heard about the Bob Hope house," he says. It seemed exactly the kind of dramatic, slightly off-the-radar location he had been looking for. "I jumped in the car and headed to Palm Springs, and I booked a hotel so I could be there overnight and see it first thing in the morning," he says. The house did not disappoint; it combined two things Ghesquiere loves that rarely come together: a connection to Old Hollywood and a bold futuristic image. "And to think that it was commissioned by a couple in their 70s!" he says to me. "It was my first experience with Lautner. We were mesmerized."

Since then, Ghesquiere has staged fashion shows at the old TWA terminal at JFK Airport (now the TWA Hotel) by Eero Saarinen in New York; Louis Kahn's Salk Institute in La Jolla, California; I.M. Pei's Miho Museum outside Kyoto, Japan; and Antoni Gaudi's Park Giiell in Barcelona—all works by modern masters that, with the exception of TWA, are a bit off the standard tourist route. "I like having people get to an architectural location, to a place that is extraordinary, and then having them get to know it," he says.

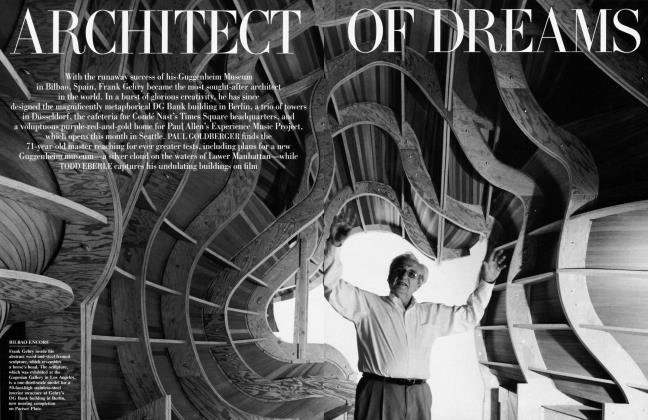

You wonder if Ghesquiere, if he were not so busy designing clothes, would be happy leading architectural tours around the world. He talks to me about traveling with Frank Gehry, with whom he shares a boss, Bernard Arnault, the chief executive of LVMH, who has commissioned the architect to design several projects, most famously the Fondation Louis Vuitton, the museum at the edge of the Bois de Boulogne, another extraordinary location in which Ghesquiere has staged a show. The 96-year-old Gehry, Ghesquiere says, has helped him to a deeper understanding of Los Angeles. "I love Frank Gehry," he says. "I cherish him."

As for the Wolff house, Ghesquiere says it is a "work in progress." He and Kuhse have been building on the prior owners' work, tweaking a few details, updating the mechanical systems, and restoring the pool—a composition of white tile whose angular shape reflects the lines of the house but somehow lost its original surfacing over the years. And they have brought in their own furniture, which is far from the cautious, consumer-friendly midcentury-modern furniture that hlls so many houses of that period. No Eames or Breuer or Saarinen chairs here; instead, the couple has added less common modern pieces like a chaise by Martin Szekely, a pair of armchairs by Paolo Deganello, and two classic lounge chairs by Jean-Michel Frank.

Their goal is not to change the house but to gently make it their own. Uncertain about what art they wanted in the two-story living room, Ghesquiere and Kuhse each chose a classic him poster that they attached, unframed, to the wall, a way of both celebrating their love of him and asserting their presence in a manner that would not affect the architecture. (Ghesquiere's selection was Gloria, with Gena Rowlands, from 1980; for Kuhse, it was a French poster for the 1971 movie The Devils, with Vanessa Redgrave and Oliver Reed.) The previous owners had a grand piano in a glass-enclosed corner of the living room, which Ghesquiere and Kuhse replaced with an elegant, minimalist turntable for vinyl records, set on a trio of stone tables by Comme des Garmons. (Their collection includes Joy Division's compilation album, Substance, as well as soundtracks from The Graduate and Alien.)

The living room is at once monumental and intimate, but then again, you could say that about the entire house. There is only one bedroom, a suite below the living room; an adjacent guesthouse, added by Lautner two years after the main house was completed, has two additional bedrooms, with an outdoor seating area containing a firepit between the two structures.

From the street, the complex appears so understated as to be almost invisible. You don't see much except the carport, and then you notice that it is punctuated by a couple of angular details that recall the work of Wright, and you sense that there is something more going on than another minimalist house tucked into the Hollywood Hills. The house unfolds slowly and cinematically: A huge eucalyptus tree comes into view, then a flight of steps leading down the hill, lined by a zigzagging concrete wall. You turn to the left, and there is a glass entry door leading to a small vestibule, and then, once inside the house, you turn again to the right, and a long staircase leads down to the living room, with a stone wall on one side and a glass wall to the eucalyptus and the landscape on the other.

And then you look ahead, and you see a wall of glass, nearly 20 feet high, enclosing the living room and opening onto an outdoor deck, and then, suddenly, you realize that you are looking out over all of Los Angeles. At that point you are torn, as Lautner wanted you to be—you can open one of the 16-foot glass doors and go outside, or you can turn back into the living room and see how he has played off high spaces, low, intimate corners, and grand views, as his mentor Wright loved to do.

The house has more of the feeling of Wright than most of Lautner's architecture from the 1960s and 1970s, a point where his instincts toward a kind of romantic futurism seemed to be on the rise. The Wolff house was designed not long after Wright's death in 1959, and while there is no way to be certain, it is possible that Lautner, grieving, made the house a kind of homage to his architectural guru.

It is still very much Lautner's own. The spiral staircase down to the primary suite, and the staircase down another level to the pool on its own deck, and the stone walls and sections built around enormous old trees—they all remind you of how closely this house is tied to its site, a narrow, steep slice of land that by some measures would be considered almost unbuildable. But that, of course, is what you could say about Wright's most famous house, Fallingwater, perched over a waterfall in southwestern Pennsylvania; this house, too, both defers to nature and straddles it.

The Wolff house is in the middle of a metropolis, but for Ghesquiere, it is as much a sanctuary as Fallingwater. "It is the opposite of the Paris life we have," he says to me. "We take hikes around the Hollywood Hills and in places like the trails in Coldwater Canyon Park, and we go to the movies at the IPIC, where you can sit in comfortable seats and have a cocktail." He has become so comfortable in his home that he has all but abandoned the office he set up for himself in a small room next to the gym. "I love to make my drawings everywhere—at the kitchen table, out on the terrace. You open the big glass doors and go out on the terrace and you forget if you are inside or outside. It is like the whole house is a studio—it is a fantastic place to work, and when we leave it to go back to Paris, it feels like saying goodbye to a person you love."

When Ghesquiere is planning one of his collections that will be shown in the surroundings of a great work of architecture, he says he thinks about what he imagines people would wear in that place. And at home in Los Angeles, he is similarly inspired by the Lautner house that is now his own.

"In my head I am inventing the perfect wardrobe for that house."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now