Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWHISPERS FROM THE WINGS

Acton Davies

IT IS a long time since theatredom has witnessed such a peculiar upsetting of expectations as that which occurred this winter in Boston. "Within the Law" had been booked for presentation at the Plymouth Theatre, but owing to its enormous success in New York and the consequent extension of its run, the owners of the theatre found it necessary to place there some other attraction. So on Christmas Day, merely as an experiment, they produced a Secret Service drama by Roi Cooper McGrue with William Courtenay in the principal role. This play was expected at best to run for only a few weeks until the original "Within the Law" company could get away from New York to fulfil their contract; but "Under Cover," the substitute, leaped into instant popularity with the critics, and after two weeks of very ordinary business, the public suddenly seemed to come around to the opinion held by the reviewers.

At all events, just as Manager George Tyler had made up his mind to ask Managers Archibald and Edwin Selwyn to vacate the premises, "Under Cover," from playing to a meager five thousand dollars a week, took a sudden jump and began to draw between eleven and twelve thousand. At these figures it continued to play for ten weeks, by which time "Within the Law" was ready to come to Boston. To withdraw a play which was drawing such box office receipts would of course be nothing short of financial suicide, and so the Selywns wisely presented "Within the Law" at another theatre. The joke of the whole affair is, however, that while "Within the Law" opened to enormous business and has been playing a most successful engagement with Jane Cowl in the leading part, yet at no time has it approached in Boston, either in receipts or in popularity, the play that had been intended simply to serve as its own stop gap.

"MO MORE old roles for me! Give me a new part every time! " exclaimed Sam Bernard after his reappearance as Hoggenheimer in "The Belle of Bond Street," which used to be ten years ago "The Girl from Kay's."

"It is so much harder to re-learn an old part than it is to learn a new one that I never was so nervous and 'up in the air' as when I stepped on the stage to-night. You see I had fooled myself. I thought that I knew Hoggenheimer as a role backwards. But when Mile. Gaby Deslys in her broken English began to hand me the cues which used to be spoken in straight Americanese, I nearly died. Every line of my role went from me and when it came to my singing my new son", 'Who paid the rent for Mrs. Rip Van Winkle when Rip Van Winkle was away?' and they kept calling for more when I had exhausted all my encores—well, I was so knocked out, so razzle-dazzled that I couldn't even think of using Hoggie's old stock phrase, 'Sufficiency!' "

OF ALL the comic opera revivals New York has known in the last generation none has equaled or even approached in magnificence the Shubert's gigantic revival of "H. M. S. Pinafore" at the Hippodrome, but big as has been its success, the audience at the Hippodrome, in their own way, have been as great a revival as the Gilbert and Sullivan masterpiece itself.

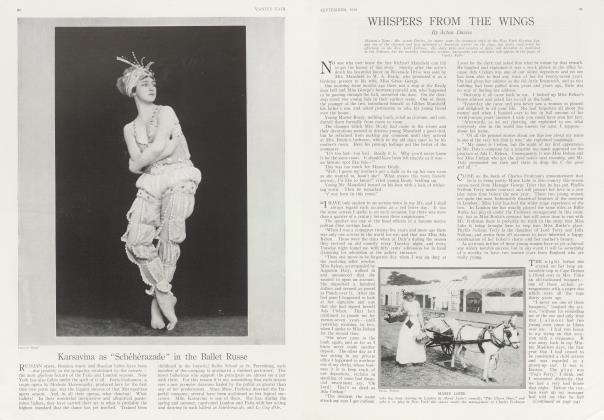

Arthur Voegtlin, the scenic artist whose genius as a painter and

deviser of unique stage properties has made this production the biggest thing of its kind in theatrical history, stood on the corner of Forty fourth Street the other day at five minutes before seven o'clock watching that great queue of humans at the Hippodrome, which ever exceeds the length of an ordinary crocodile.

"There are queues and queues," exclaimed Voegtlin admiringly as he watched the long line of men, women and children standing two and three deep almost as far down the block as the entrance to Sherry's. "When it was decided to put 'Pinafore' on, I said to myself, 'It will be a hit if we do it on an unprecedented scale, but it will be goodby to our queues'—that is to our gallery public which is perfectly willing to stand in line for an hour or more, provided they get first chance at the front gallery seats. It never occurred to me that 'Pinafore' would make an appeal to them at all. Heretofore in all the big Hippodrome attractions the gallery audience after the first few weeks are drawn from their Bowery, from Harlem, from the Bronx and the remotest and cheapest suburbs. The foreign element always prevails in our queues, for American and English-speaking playgoers don't at all fancy that long wait in line before the door opens. But just to show how far wrong I was—the queues since 'Pinafore' opened have been longer than ever before; and they are composed almost entirely of Anglo-Saxons; the foreigners are now a rarity. Some nights this long line of well-dressed men and women makes me think, in a way, of the lost legion. At least they seem to represent some of those thousands and thousands of Lost Audiences which by the high cost of theatre going, the inferior average of attractions and the cheapness and the excellence of the bills offered by the 'Movie' houses have gradually been weaned away from the regular theatres.

"WATCH the queue on any of these nights and you will see families standing there in line representing as many as four generations. And all of them, save the youngest representative of the family, know the 'Pinafore' backwards. It's just thirty-six years since 'Pinafore' was first produced in London and it must be remembered that it was less than a year later that the 'Pinafore' cyclone struck America and raged for many years from coast to coast.

"The 'Pinafore' furore seems to be a lasting one, for after the professional and church choir companies had sung it to death for three or four seasons, the children companies started up in all parts of the country, and after that the audiences in every city and hamlet started in to massacre the poor old score according to their lights, so you see-"

Before he could finish a motor stopped directly in front of him, and leaning out of the window a beautiful blonde in a flower hat reached forward and grasped him by the hand.

(Continued on page 88)

(Continued from page 37)

"Just as one of the noble army of 'Josephines' I want to shake your hand, Arthur Voegtlin," exclaimed Miss Lillian Russell. "That ship of yours is the most wonderful craft that was ever on land or sea. If only poor old Gilbert and Sullivan could have lived to see it! As for me it carries me 'way back to the old days at Tony Pastor's when I sang Josephine with Flo Irwin as Ralph Rackstraw and May Irwin as Buttercup."

"I know you two must be talking 'Pinafore,' chirped a red-haired little woman who was just about to cross the street. As she paused to speak to Voegtlin the lights revealed the smiling features of Mrs. Fiske.

"I know 'Pinafore' backwards to this very day," she exclaimed; "it's the one play which I have appeared in of which I can remember every line."

IF ANY effete individual in search of a new thrill would obtain an introduction to either or both of those brilliant authoresses, Miss Elizabeth Jordan or Mrs. Mary Roberts Rhinehart, by asking them a single question he could obtain from either source all the ingredients which go to the making of a brand new thrill. Mrs. Rhinehart's sole venture as a playwright has been a dramatization of one of her own books called "Cheer Up." Mrs. Jordan's only essay as a playwright was called "The Lady from Oklahoma."

The only question which it is necessary to propound to either one of them is this:—

"What is your personal opinion of theatrical managers and stage producers?"

WHAT do I think of theatrical managers and their stage producers? Well, for one thing, there isn't enough money left on the face of the earth to induce me to come in contact with either of these strange species of human again. The way of the transgressor may be hard and the path of the average woman novelist is not paved with asphalt or strewn with rose leaves, but short of breaking stones in the street I can think of no occupation more arduous and humiliating for a woman than to have to submit one of her plays to a theatrical manager, and then sit quietly by and watch his chief factotum try to put it on the stage. For a writer of any recognized position to submit one of her plays to a theatrical manager is little short of artistic suicide. Individually, she will find herself suddenly transformed from the Fairy Queen ruling omnipotently over all her characters to Cinderella cleaning out the theatrical manager's pots and pans. Neither scenes nor characters nor dialogue are sacred to these illiterate ghouls in their frantic efforts to make an inconsistent play out of a perfectly good and successful novel. The fact that you have won a place for yourself in the literary world only eggs him on to vent more insults and ignominies upon both the writer and her manuscript. In these days when publishers pay so liberally for good work any woman is a fool who allows her novel to be dramatized even if she makes the dramatization herself—for by the time the producer has presided at a few rehearsals she won't be able to recognize the child of her brain even with the aid of an opera glass."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now