Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSUCCESSFUL AMERICAN PLAYWRIGHTS

Showing that During the Past Twenty Years Only a Baker's Dozen of Them Have Scored Repeated Successes

Acton Davies

THERE is just one thing more difficult to do than to write a successful play, and that is to write another. The man who has achieved two real successes assuredly has every reason to hold his head high. If he can turn this double achievement of his into a habit, he may consider himself among the seven wonders of the world, to say nothing of the theatre. A dramatist never finds greatness thrust upon him; it comes only after hard work and disappointment.

The list of American playwrights whose first play was produced less than twenty years ago and who have achieved more than one real success is not a long one. There are not more than a baker's dozen of them. But the theatrical casualties during that time would fill a volume. There are many who have been killed outright on a "first night," and the wounded constitute that army of writers of unproduced plays who yearly bewail the decadence of the American theatre.

The first success is a luxury; the second one is a necessity if one wants permanent recognition as a dramatist. Heaven knows, the first is difficult enough to give birth to; and the greater the success which is scored, the greater is the task of duplicating it. It has now become a theatrical bromide, that "plays are not written; they are re-written." Dion Boucicault may have said it; or Disraeli. But whoever the wiseacre was, he might at the same time have added: "It is always the dramatist's second play that requires the most re-writing."

THERE is no reasonable explanation of why this should be. If there were, then every dramatist would be a sure shot, and hit the theatrical bull's eye not only once, but again and again. When his first success comes, the playwright sets himself a standard which he is expected to maintain.

It is the popular belief that play-writing is a nice little game, wherein dialogue is pieced together—and there you are! But the dramatist who has his first success usually looks backward over and ponders well the bitter fruit of experience. And nine chances out of ten he regards his temerity with wholesome awe, and he wonders at the rash bravery and confidence with which he set out to achieve his goal.

Rare indeed is that citizen of the United States who is not writing a play. There are thousands of manuscripts toiling through the managers' offices; there are thousands of people deceiving themselves in the conviction that the managers do not know good plays when they see them. Let these multitudes get over the idea that drama is merely talk. You remember what Dion Boucicault—this time I am sure it was he—said to the young playwright who had brought him a six act melodrama to read. "My boy," exclaimed the jovial Irishman, "go home and write your dialogue as though each sentence was a telegram and had to be paid for." I hat is what all dramatists have to remember; that is why so many plays have to be re-written and re-written.

BEFORE we consider the older playwrights of America, the men whose reputations date back twenty years or more ago, we ought to take a casual view of the younger luminaries in our theatrical sky, and, in justice to his present great successes, we must begin with George M. Cohan.

He is one of those lucky individuals who can see the bull s eye blindfolded. A genius of the theatre in almost all its branches, he possesses, more than any other man, the ability to catch hold of popular favor. George Ade's slogan has always been: "Keep your eye on Cohan." He has scored so many hits that we have lost count. Before he came to us at the Fourteenth Street Theatre with his first full-length play, "The Governor s Son," he had had rapid-fire success in vaudeville, and his songs had been whistled on the streets. He is so busy, so prolific as actor, manager, playwright, song writer, etc., etc., that he hasn't time to spend his royalties that would pay the yearly salaries of two, or more, presidents of the United States.

When Eugene Walter dawned upon the horizon everyone said: "Who is this new man?" But Walter had haunted the managers' offices for many a day, and if he did not, as theatrical tradition has it, sleep on park benches, he did bury himself in hall bedrooms until "Paid in Full" brought him a surplus over his weekly board. And he is an example of the dramatist who, having gained success with a supposedly "first" play, beat his record when he wrote "The Easiest Way." He has had failures and moderate successes. But among our recent men he has most quickly established himself as a figure to be reckoned with in any account of the American theatre.

"EVEN younger, but equally as virile and more romantic than Walter, is Edward Sheldon, who began when he was an undergraduate at Harvard to show his ability. "Salvation Nell" made him independent, and then he began writing plays as quickly as he could fire his dramatic gun. Beginning with the brutal realism of "Salvation Nell," he followed it with a play of grim vigor which he called "The Nigger." This was one of the rare American finds made by the New Theatre during its checkered career. Sheldon is a dramatist with a grip to him. "Romance" is probably his greatest popular success.

At times it seems as though there should have been more sharpshooters in the theatre than there are. Hoyt's farces in the past made him a fortune; Franklin Fyles went forward on the wave of collaboration. Paul Potter, author of plays, adaptations, and translations, gave the bull's eye a resounding whack when he dramatized DuMaurier's "Trilby." Paul Armstrong, after a bitter struggle for success, cornered it at last with "Salomy Jane" and "Alias Jimmy Valentine." But all of these men had to knock at the door many times, only to find no one at home within.

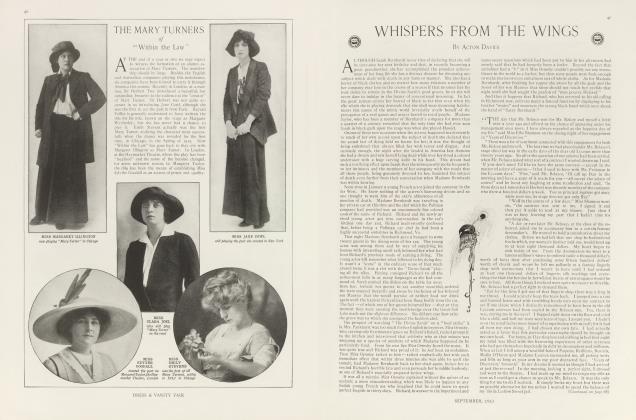

HOW about Bayard Veiller and "Within the Law"—one of the greatest financial successes of modern times—and Broadhurst's "Bought and Paid For" and Manners' "Peg o' My Heart," whose success nothing seems to disturb? Well, they too have established records, and they too have had their failures. George Ade seems to have retired on his laurels, which, to judge by the fortune made from "The College Widow," might easily be wrought of gold. But after all these men are lined up in a company which we might register as "repeaters," they are small in number as compared with the Coxey's army of the unsuccessful. Tully and DeMille and Knoblauch have their guns shouldered and they are firing around the bull's eye, DeMille hitting once with "The Woman," which contained some of the best and strongest dialogue he has written, and there are other recruits. But the drama—like the army and the navy—needs more men. Tempting royalties are the inducement. The requirements are to hit the target twice.

AND now let us go back a little! Back for twenty years or so: Bronson Howard is known as the Dean of American playwrights, because when he began to write in 1870, the American stage was dominated by English and French importations. "Saratoga" won its way despite the fact of its being written by an American. Daly, Wallack and Palmer had little faith in the home product. But Howard demanded a hearing and he at last succeeded. Then through careful feeling of his way he followed his first play with dramas of varying value, his most distinctive pieces being "The Young Mrs. Winthrop" (1882), "The Henrietta" (1887), served to us this year in up-to-date form, and "Shenandoah" (1889), one of our first war dramas. These were interspersed with various failures, but in all of them Mr. Howard displayed an apt hand, and they brought him a substantial fortune.

(Continued on page 98)

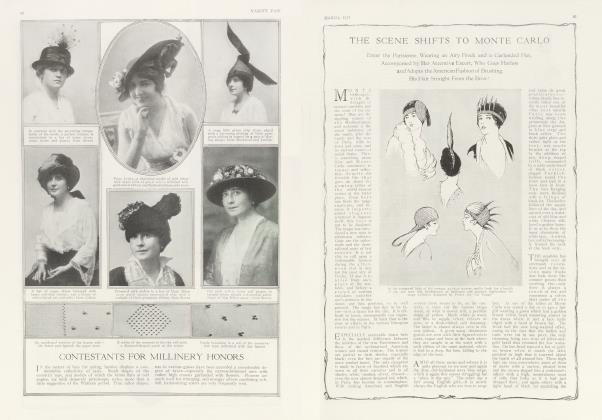

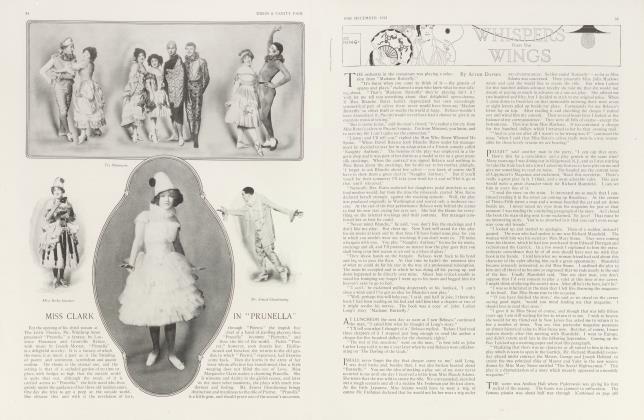

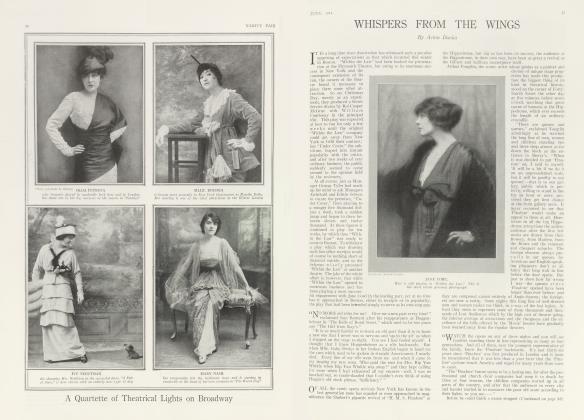

Four of our likely young playwrights, each a master in his vein

(Continued, from page 31)

JAMILS A. HERNE had bitter experiences before his plays began to make him money. "Shore Acres" (1892), his most pronounced success, is the play least representative of his fine technique and his advanced realism. "Margaret Fleming" (1890) and "Griffith Davenport" (1899) were more artistic successes than popular dramas, and it was a concession made to public demand when he wrote "Shore Acres" and followed it with "Sag Harbor" (1899). He began playwriting late in life — after he had gained reputation as an actor. His success in this direction was the least claim Herne had to distinction. Unfortunately, the only copies of "Margaret Fleming" and "Griffith Davenport" in existence were burned during a fire which totally destroyed his country home.

Take the case of Clyde Fitch. Instant fame came to him in goodly measure with the production of his first play, "Beau Brummel" (1890). But having sold his rights to that bric-a-brac drama for a mere song, he had to wait some years before another success came to him, even though he was producing all the time. He was very uneven in his work, but there was always something of Clyde Fitch about it, and considering the number of his plays, the proportion of successes was astounding. Take "Nathan Hale" (1898), "Barbara Frietchie" (1899), "The Girl with the Green Eyes" (1902), and, most distinctive of all, "The Climbers" (1900). Truly, Fitch was an adept at hitting the bull's-eye. Probably no American dramatist could get quite as many plays accepted as he. Managers seemed to fall over themselves making contracts with him, and the saying used to be: "If you don't want to accept Fitch's play on the spot, refuse to have him read it to you." He was a wonderful interpreter of his own plays. Look into his early career, however, and the young playwright spent long months of famine and distress, during which time he piled his trunk with manuscripts no one would take. And most of the plays that fail after the first success are those the successful dramatist finds in his trunk.

AUGUSTUS THOMAS, after a mild little success with "Editha's Burglar" in 1887, a dramatization at that, waited several years before "Alabama" (1891) brought him into prominence, and between that time and the production of "Arizona" (1900) there were many failures. Then there came an unequal period of farce, with "The Earl of Pawtucket" (1903) as the high-water mark, and again a long slump in the market of prosperity ; then mental suggestion came to his rescue in "The Witching Hour" (1908). His target practise has been long and varied, and sometimes he has gone so wide the mark that we have thought his dramatic eyesight hopelessly impaired. But his claim to a position among successful dramatists cannot be disputed.

David Belasco won his first individual success with "May Blossom" in 1884. But he had been experimenting with other dramas for many a day before that, and in the capacity of stage manager for the Madison Square Theatre, had helped to put into shape many plays by others. Bronson Howard often spoke of what Belasco did toward helping "The Young Mrs. Winthrop" to success. It was during these days at the little Twentyfourth Street playhouse — now a thing of the past — that he and Henry C. DeMille became associated. Together these two went over to the Lyceum Theatre on Fourth Avenue, and there collaborated in a series of plays that practically made the history of the Lyceum at that time. There was "Lord Chumley" (1888), with an eccentric role for Sothern, and, in rapid succession, there were "The Wife" (1887), "The Charity Ball" (1889) and "Men and Women" (1890). Sothern, then at the outset of his career, took from an old trunk a manuscript which he handed to Belasco; the result was the rehabilitation of "The Highest Bidder."

So the story went — the beginning of that wizardry which later brought Mr. Belasco to greater distinction. "The Heart of Maryland" (1895), "Du Barry" (1900), "The Girl of the Golden West" (1905). and "The Return of Peter Grimm" (1912) represent his quick-firing record. And there are the younger playwrights who owe him a debt of gratitude. It was he who launched John Luther Long in a series of dramas beginning with "Madame Butterfly" (1900) ; Tully in "The Rose of the Rancho" (1906), and others. It was he who had the bravery of his convictions in presenting Walter's realistic "The Easiest Way" (1909). His name has been associated with some of the greatest successes in the history of the American stage.

CHARLES KLEIN had a weary road to travel before he received a commission from Belasco to write "The Music Master" for David Warfield. There are few people who remember that he wrote the libretto for Sousa's "El Capitan." Ask Klein himself about those days, and he will tell you that some of -the best dramatic work he ever did was at that time turned down by the managers. Then on the top wave of public interest in business condition, Klein wrote "The Lion and the Mouse," and he was hailed as the AMERICAN DRAMATIST in capital letters. This play, with "The Third Degree," made him a fortune — so large, indeed, that Mr. Klein can afford to snap his fingers at the failures which he has made from time to time. I shall never forget his debut as a dramatist. It took place at the Harlem Opera House, which Oscar Hammerstein had just built. The play was called "By Proxy." All I can remember about that drama was that Edward Emery had the leading juvenile role, and that there was a red prayer book very much involved in the plot. But I do remember Klein's frightened little speech before the curtain. How many timid speeches of the same kind I have heard since then!

One of the most distinctive adepts at hitting the bull's-eye is William Gillette. Sometimes the unsteadiness of his hand as a playwright has been overcome by the fascinating manner of his acting. He has had his failures; he has depended upon other sources for his plots. But whatever he has done has shown technical understanding and the ability to tell an entertaining story. "Held by the Enemy" (1886), "Too Much Johnson" (1894), and "Secret Service" (1896) would alone be sufficient to establish the permanency of his position in the history of American drama.

SUCH are the men who have really won their spurs on the stage, who have really been given public favor more than once. There are others whose plays are for the few. who make special appeal. These men are thoughtful, and we may expect something from them. But our test here is whether they are quick at hitting the mark. There are bull's-eyes and bull's-eyes, you say? Yes. But there is an unmistakable ring to the theatrical bull's-eye, and you can hear it for a hundred nights or more.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now