Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

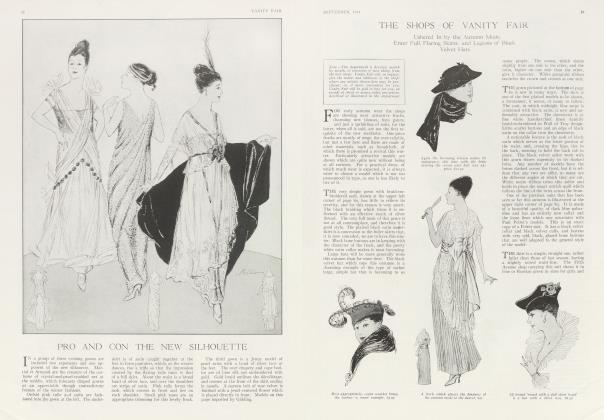

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHREE ACTRESSES OF THE SEVENTIES

The Element of Chance in the Careers of Mary Anderson, Clara Morris and Kate Claxton

J. L. F.

THE art of the player may die with him, but more than any other, it lives in the memory of those whom it has moved to laughter or to tears. The habitual playgoer delights in recollections of the past, and when two or three of an elder generation are gathered together, their talk goes back to the golden period of youth when the stage made its deepest impression upon them.

In my own younger days, actors loomed larger in the firmament of the popular imagination than they do now. The line between them and the general public had not been broken down and ruthlessly trampled upon. The old illusions, the best safeguard of the mimetic art, still existed. Actors and actresses were not "received" in society; they formed a society of their own and there was not one of us young fellows who would not have given his eye-teeth to have been admitted to it.

The element of chance enters into a stage career to a much greater extent than in any other calling, thus adding materially to the charm of the profession in the eyes of venturesome youth. Of the three famous actresses I have in mind, one owed her success to that most elusive of all accidents, the "psychological moment," while each of the others found her great opportunity in a part already refused by a fellow player.

BACK in the middle seventies, there was in New York a family of social distinction, that welcomed to its drawing-room a very few of the more distinguished singers and players, and it was there that I happened to be one evening when Colonel Henry Watterson, an old friend of the head of the house, entered, bringing with him an extremely beautiful young girl who had just come from his Kentucky town to seek fame on the metropolitan stage. When I realized that I was actually in the presence of a young and charming actress, my heart beat with excitement and I fixed my eyes upon her, listened to everything she said and wondered if I were making a favorable impression on her. Her manner was frank, friendly and extremely vivacious, and she even addressed one or two remarks to me and bestowed a winning smile upon me as she took her leave.

One thing I recall of the conversation that evening, and that is that it brought forth the fact that Colonel Watterson had, in his younger days, been an actor—a secret that he has carefully guarded ever since, for I have never met anyone save Marc Klaw who knew of it. A fortnight later the town literally rang with the name of Mary Anderson, the new stage beauty from the South.

Miss Anderson owes her fame largely to the fact that she appeared upon the scene at precisely the right moment. Shakespeare was popular at the time and Juliet had not yet been replaced by Nora as the ideal part for an emotional actress. Edwin Booth was at the height of his fame and "Julius Caesar," with; its memorable cast of Barrett, Davenport, Bangs, and other well - known players, enjoyed a sensational success at Booth's

Theatre. The country had not recovered from the panic of '73, and there is nothing like hard times to stimulate the taste for serious drama.

The theatrical planets were thus in favorable conjunction when the young Kentucky girl flashed across the heavens, a real American Juliet, beautiful in face, of swan-like figure and irreproachable character. Her presence awakened the chivalry of the nation and dulled the edge of all narrow criticism of the stage. Fire-eating Southerners dared the world to utter one word against her, and mothers bade their daughters go and behold this model of stage virtue—"so different from other actresses." In short, Mary Anderson quickly became an object of public idolatry, more because of her beauty and fine personal traits than because of her accomplishments as an actress. For ten years she pervaded our stage, attracting and giving genuine pleasure to very large audiences. Certain rather savage critical attacks brought her career to a sudden close, and she retired suddenly to return no more. During all the years that she played she never produced a single American play.

CLARA MORRIS, a contemporary of Mary Anderson, was one of Augustin Daly's most notable "finds," and an actress of extraordinary gifts; and Mr. Daly possessed a remarkable flair for perceiving and developing dramatic talent. Miss Morris came to him from a small city in the mid-west at a time when he was established in his tiny theatre in West Twenty-fourth Street, and her debut before a New York audience—the only kind of debut that really counts in the eyes of actors—was a triumph of the sort common enough in novels of the stage, but almost unknown in actual life.

Mr. Daly was about to put a new play, "Man and Wife," into rehearsal, and Miss Morris, the newest member of the company and; in the eyes of her associates, the least promising and the worst dressed, was cast for a comedy part. She went home to her mother in tears because she had hoped for a chance to show her emotional powers. She was still weeping when the stage manager arrived with the part of "Anne," which Agnes Ethel, then a dominant figure in Mr. Daly's company, had contemptuously refused. How Miss Morris created the sensation that night by her vivid and tear-compelling performance is a matter of local stage history. She had sacrificed a much better financial offer in San Francisco for the sake of appearing in New York, and her salary, at the moment of a triumph that set the whole town buzzing with her name, was $35 a week.

It was during the intense silence of one of her strongest scenes on that memorable first night that the actress heard the words, "larme de la voix," uttered b y Oakley Hall, in a private box. Unconsciously, the politician —always a lover of the stage and its people—struck the keynote of the great career of whose beginning he was that night an appreciative witness. The tear in her voice was the weapon with which the young actress went forth to conquer, and before ill health brought her career to a close there were not many playgoers in the land who had not wept with her. In the ability to portray grief, remorse, vain regrets—in short, all the elements of the bitterest heart-ache— Miss Morris had not a peer in her generation. She learned much from Mr. Daly, but after the breaking up of his stock company she drifted away to other managers and her art did not improve. But "les larmes de la voix" carried her along in triumph. The generation that knew her remembered Matilda Heron, but had not seen such finished art as that of Bernhardt and Duse. Wisely enough Miss Morris refused every invitation—and it is believed that she had many—to appear in London, and it is quite likely that if she had appeared there her pronounced western accent would have spoiled her chances of success.

(Continued on page 98)

(Continued from page 56)

NOW for our third great favorite of the seventies. The fame that came in a single night to Kate Claxton was a matter of amazement to her fellowplayers for her part was so small that they had felt genuinely sorry for her.

During what some local wit has called the '"A. M. Palmy days of the Union Square Theatre," the manager, realizing the necessity for a change of bill, bethought him of a manuscript that had been lying for several months in a dusty pigeon-hole of his desk. The original piece was still running to enormous business at the Porte St. Martin in Paris, and Hart Jackson, who had secured the American rights had relinquished them for a few hundred dollars.

It must seem strange to those familiar with modern theatricals that the manuscript of a notable Parisian success could have thus lain gathering dust in New York. In these days of keen competition a successful first night in Paris, Berlin or London, attracts innumerable American agents, managers and players, and an unmistakable success sends them all scurrying to the stage door to secure the rights for this country.

IT was Rose Eytinge, an artist of real gifts, who gave Miss Claxton the first great opportunity of her life by refusing the part of the Blind Orphan because, measured by the foot rule—the actor's usual standard —it was the smallest role in the piece. The play was produced in superb style, Mr. Palmer going to the pains and expense of sending his stage manager, Mr. John Jarselle, to Paris, to study the Porte St. Martin production and to procure the very best scenery, costumes and accessories obtainable. The cast included that fine leading man, Charles R. Thorne, Miss Marie Wilkins, McKee Rankin, Kittie Blanchard, Mr. Parselle, Miss Eytinge and Mr. F. F. Mackey. The stage carpenter died a few days before the production and his successor found much difficulty in handling the heavy scenes so that the first performance lasted until almost two o'clock in the morning, but, in the words of Mr. Thorne, "not a soul stirred."

If Miss Eytinge had really understood her art, she would have known that the "Blind Orphan"—who knew, because of her affliction, less of what was going on about her than any of the other players—was sure to become the center of interest to the audience. So great was Miss Claxton's success that she afterwards toured the country for many years, playing the Blind Girl as a star part, and amassed a fortune from the play.

Each one of these three actresses is still living. Miss Anderson is married and living in England; Miss Morris is a helpless invalid, and Miss Claxton, who, to a remarkable degree, retains her appearance of youth, is still occasionally seen on the stage.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now