Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE FIVE WORLD MASTERS OF LAWN TENNIS

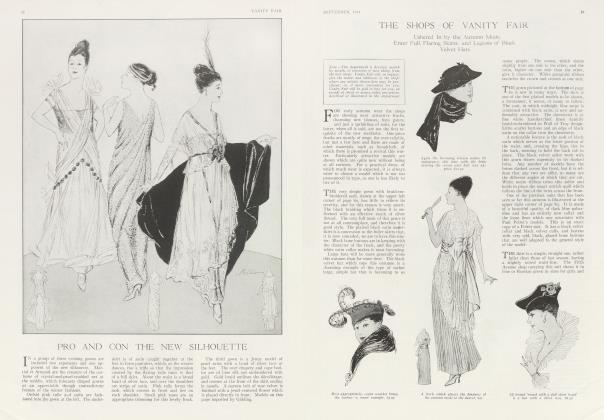

An Australian, an American, a New Zealander, an Irishman and a German An Analysis of Their Widely Divergent Styles of Play

J. Parmly Paret

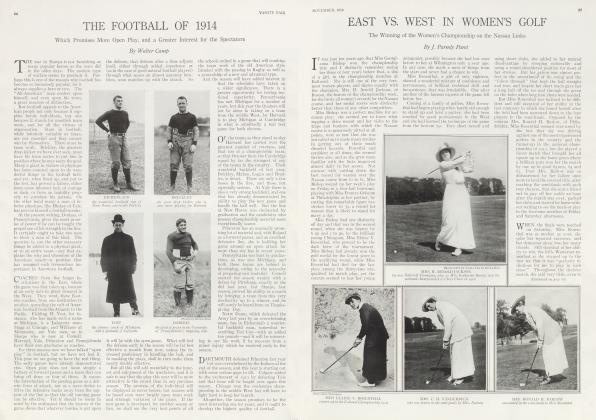

DESPITE the often heard complaint of the dearth of exceptional championship material in the lawn tennis world to-day, there are, this season, live great masters of the game in active competition and all of them took part in the recently completed International matches.

These five players represent five different countries, and this fact again demonstrates, if further demonstration be necessary, the worldwide vogue of lawn tennis. I doubt if there is another sport in existence in which the rules and playing conditions in various widely separated countries are so uniform, or one in which its most expert representatives throughout the world are so evenly matched.

This year's Davis Cup matches brought together teams from England, France, Germany, Belgium, Australia, Canada and the United States, and four of these countries were represented by players of the highest possible skill. Putting aside stars of the second magnitude, Australia sent Norman Brookes and Anthony F. Wilding, England sent John C. Parke, Germany sent Otto Froitzheim, and we entered our own champion, Maurice McLoughlin. Say what you please of the rest of the field, and of America's defeat, these men have earned places on the roll of honor of the tennis world. All are masters, though no two play the game alike.

"DROOKES has been past master of the game for nearly ten years. He is a crafty general of a school that is all his own. Although past his first youth, he still retains his old skill and stamina, and this year, after it had been predicted that he could not "come back," he journeyed from Melbourne to Wimbledon, and going through the huge field for the All England championship, won the title by beating Froitzheim in the finals and Wilding (three straight sets) in the challenge round. His work in the Davis Cup this year is too fresh in mind to require comment.

Brookes is so unorthodox, one might almost say so awkward, in his style of play, that his marvelous skill seems almost uncanny. There probably is no other player in the world who uses the same style of strokes, the same grips and the same position on the court, and yet he is a genius in working his opponent out of position, and machine-like in his ability to take advantage of the winning openings his tactics have produced.

Brookes learned h i s tennis on his native heath, there developed his own style and demonstrated its superiority in other lands. He is strictly a self-made player, never having had the advantage of learning from others of great skill. He was considered invincible until Parke went out to Australia in 1912 with the English challenging team and startled the tennis world by beating the mighty Brookes in a brilliant match. Since then it has been the Australian's ambition to regain his lost laurels, and in this he certainly succeeded at Wimbledon.

WILDING, while a New Zealander by birth and eligible to play on the Australian team, seems better qualified to play for Great Britain. He has held the English championship for four years, and has made his home in England. His play, also, has been developed in the mother country and against other Englishmen, so that his tennis is really more English than Australasian. Thoroughly orthodox in style, he is a marvel at what might best be described as aggressive defense. He does not go right after his man as does McLoughlin, but his strokes have a killing power that is wonderful when one considers his deep position in court. Only two or three players the world over have developed an attack strong enough to break through his defense, and no player we have ever seen, unless it be the former champion, H. L. Doherty, has the same ability to meet his antagonist's attack with strokes that so soon force him to a defensive game. Wilding's success against McLoughlin's terrific service, which most players find so difficult to return, lay in his hitting the ball shoulder high, and it told greatly in his favor many times. No matter how hard pressed, Wilding, from even the most difficult positions in court, is always dangerous and no ace is earned against him until the ball is out of play.

McLOUGHLIN, the lanky, red-haired California youth, joined the charmed circle of masters after Wilding. Close followers of the game heard of the "boy wonder" out on the Pacific Coast nearly ten years ago when he was still in his teens. Seven years back he won the Pacific coast championship, and yet, to-day, he is only twenty-four years old. When only a youth of nineteen he was sent out to Australia on the American team that tried to regain the lost Davis Cup. The task proved too big for him, possibly because of his lack of knowledge of grass court play, his experience having been entirely on hard courts.

Since that time, however, he has so improved his game, that he is now admitted the greatest player alive. Like the Australian his play is in many ways unorthodox. His is the genius that transcends the accepted laws governing good form in tennis, as is Brookes, and he wins despite of it. Perhaps the greatest weapon in the armory of the American champion is his wonderful service, of the true "American twist" type. This form of delivery he has carried to a point that it has never before reached. The speed, break and bound give a length and spinning impact to the ball that make it very difficult for even the best players to handle.

(Continued on page 96)

(Continued from page 64)

XT to his wonderful service, McLoughlin's best asset is his disposition. I do not remember ever seeing a player more intent on winning a match, or one who could keep up sustained attack so persistently during prosperity and adversity. There is no let-up to it, and no matter how hard he is panting, or how hot the sun may be, he allows himself no resting spell until the match is over. I do not remember ever seeing McLoughlin finesse in his play, and I often wonder what will happen when he meets, if he ever does, a man who can force him to take the defensive.

McLoughlin's back-hand is played in distinctly bad form, yet he is not so weak on his left side, as one would imagine on seeing him hit the ball. The stroke is played too close to the body, with the elbow cramped and with too little follow-through to give the ball speed or to control its direction accurately. Even his forehand stroke could be improved upon but his smashing, like his service, is almost incredibly accurate and severe.

PARKE broke into the charmed circle of world masters rather suddenly and unexpectedly only two years ago by his victory over Brookes in Australia. Even then there were many who thought this match only a flash in the pan until he had justified a higher estimate of his skill by beating McLoughlin and Williams at Wimbledon last season in the International matches. There is also a victory over Wilding to his credit.

Parke is a player of the orthodox English school, with a magnificent defense, and ground strokes that it would be hard to improve upon. In passing an adversary at the net, and in cutting the ball off at sharp angles when he has drawn his opponent out of position, particularly when he has lured his man inside the court, Parke is exceedingly clever. He is at his best in the back court, but he can volley well in the English style with his wrist down low and he seldom misses a chance offered for an overhead kill.

UNTIL last year Froitzheim had yet to earn his spurs in the fastest company, but in the Cup matches of 1913, the German had a lead of two sets to love against McLoughlin and for a time looked like a sure winner. The American pulled this match out of the fire, but only after a terrific struggle, his stamina standing him in good stead toward the end when the German eased off a little in his play. This year, Froitzheim not only beat Parke in four sets during the English championship, but played Brookes the full five sets in the finals, and forced him to 8-6 in the fifth set, at one time actually being within a few strokes of victory.

Wilding's opinion of the German is flattering: "Froitzheim has developed the most accurate passing shots I have ever seen. He hits them slowly and within an inch or two of the top of the net and side lines. He is particularly good at hitting from angles." The Continental champion makes his ground strokes with machine-like accuracy and he is always sound in his play and position in court. As a volleyer he is only fair, but on the other hand, not even the best volleyer can afford to take chances with him in the net. Give him an opening no larger than the width of a tennis racket and he drives the ball into the hole with unerring accuracy.

THESE are the aristocrats of the lawn tennis world —no two of them alike, of many breeds, lands and styles of play. The natural question s: "What, then, makes the great master of the game, >'f these men have so few characteristics in common?" And that is a question which no man can answer. Nature does not always co-ordinate her tools with the labor they are to accomplish. W. Byrd Page jumped six feet four inches and he was only about five feet six inches'tall; N. F. Sweeney, the next record holder, stood some eight inches taller, yet his performance was marveled at when he jumped an inch and a half higher. Your little sprinter holds his own with the big man; nature makes up to him for his small size by giving him less weight to carry. With a stride ten inches less, he runs as fast as his long-legged rival.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now