Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

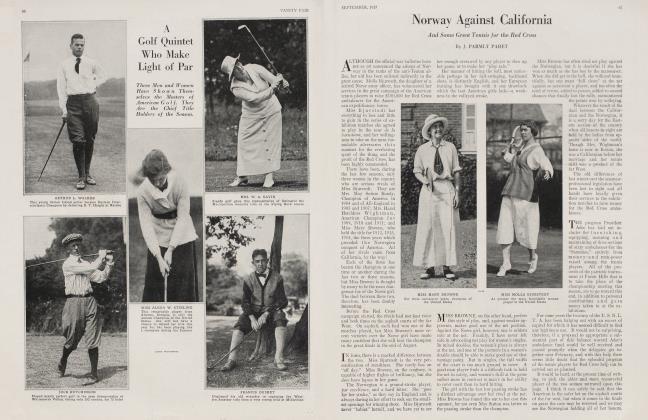

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEAST VS. WEST IN WOMEN'S GOLF

The Winning of the Women's Championship on the Nassau Links

J. Parmly Paret

IT was just ten years ago that Miss Georgianna Bishop won the championship title and I distinctly remember seeing her three or four years before that, a slip of a girl, in the championship matches at Baltusrol. She is still one of the very foremost women players, and shares equally with the champion, Mrs. H. Arnold Jackson, of Boston, the honors of the championship week, for she broke all women's records for the Nassau course, and her medal scores were distinctly better than those of any other competitors. Miss Bishop was a perfect machine for accurate play; she seemed not to know what topping a drive meant and her visits to the traps and bunkers with which the Nassau course is so generously pitted at all points, were so rare that she was not called on to waste many strokes in getting out of these much dreaded hazards. Powerful and confident at all times, she seemed tireless also, and as she grew more familiar with the links improved almost daily in her scores. Not content with cutting down the best record for women over the Nassau course from 82 to 81, Miss Bishop wound up her week's play on Friday in a four-ball foursome, playing with Miss Frances Griscom of Philadelphia as her partner, by cutting this remarkable figure two strokes lower to 79, a record for women that is likely to stand for many a day.

Miss Bishop had one distinctly off day and that was in the second round, when she was beaten by 6 up and 5 to go, by the brilliant young Chicagoan, Miss Elaine V. Rosenthal, who proved to be the dark horse of the tournament. Miss Bishop had already won the gold medal for the lowest score in the qualifying round, while Miss Rosenthal had tied for the last place among the thirty-two who qualified for match play, yet the veteran seemed to fear her young antagonist, possibly because she had lost once before to her at Wilmington only a year ago. In any case, she made a mess of things from the start and never had a chance to win.

Miss Rosenthal, a girl of only eighteen, showed a wonderful mixture of confidence and nervousness, of brilliant technical skill and inexperience, that was irresistible. One after another of the famous experts of the game fell before her.

Coming of a family of golfers, Miss Rosenthal had begun playing when barely old enough to stand up and hold a putter; she had been coached by good professionals in the West and she had learned the technique of the game from the bottom up. Very short herself and using short clubs, she added to her natural disadvantage by stooping noticeably and using a round-shouldered position for most of her strokes. But her action was almost perfect in the smoothness of its swing and the "follow through" that kept the ball straight and true, and despite her short reach gave her a long ball off the tee and through the green on the holes when long iron shots were needed.

But Miss Rosenthal was inclined to be diffident and still skeptical of her ability in the fast company in which she found herself after the field had been narrowed down to the four players in the semi-finals. Opposed by the veteran Mrs. Ronald H. Barlow, of Philadelphia, Miss Rosenthal seemed over-awed by the fact that she was driving against one of the most experienced golfers in the country and the runner-up in the national championship of 1912, but she played a clever match that brought her all square up to the home green where a brilliant putt won her the match by one up in good figures, 84 and 83. Poor Mrs. Barlow was so disheartened by her failure once more to land the coveted title, after reaching the semi-finals with such rosy chances, that she sent a friend out to pay off her caddy an hour after the match was over, packed her clubs and started for home without waiting to see the finals or play in the foursome matches of Friday and Saturday afternoons.

THEN the finals were reached on Saturday, Miss Rosenthal was as modest as ever, despite her repeated successes, and her demeanor alone won her many friends. Still skeptical of her ability to win, the little Westerner remarked as she stepped up to the first tee that it was "perfectly ridiculous for me to play in such class!" Throughout the decisive match, she said very little, even to her sister who followed close in her wake, or to her caddy, but stood so pluckily behind her guns that it was not until the last putt on the last green had been "sunk" that she was forced to acknowledge defeat. Always "down" from the very first hole she was never able to square the match, although she made a brilliant rally beginning at the twelfth hole, and from 3 down and 7 to go—a lead that seemed too big to overcome—Miss Rosenthal pulled the match up to only I down at the fifteenth hole and halved all of the last four holes with the champion, lighting hard at each for the much-needed single stroke that would have halved the match at any one of them.

Continued on page 86

Continued from page 57

IN marked contrast to Miss Rosenthal, was Mrs. H. Arnold Jackson, of Boston, the new champion. As Miss Katherine C. Harley, she won the national championship at Chevy Chase, in Washington, back in 1908, and she has perfected her game a great deal in the meantime. With plenty of tournament experience to fall back on, Mrs. Jackson seemed confidence itself all through the tournament and her play showed it all along. Tall, with a long reach and plenty of weight, she seemed twice as large as her little Western rival in the finals, and she hit the ball with supreme confidence that did not seem to check up with her frequent comments on the shortness of her wooden shots.

At the long fifth hole with the dreaded railroad track close at the left and a miserable ridge-plowed border hazard at the right of the narrow fair-green, Mrs. Jackson sent away a good drive of nearly two hundred yards straight up the centre of the course, but remarked rather contemptuously as she stepped down from the tee for her opponent to drive, "Not much distance, but I was scared to death of that railroad track." At the difficult eighth hole over a pond, Mrs. Jackson drove as steadily over the water as a professional, while her nervous young rival topped her drive into the water, drawing from the champion the comment "Oh, that was hard luck!"

BUT Mrs. Jackson certainly used her head as well as her clubs, for twice during the final eighteen holes, on the seventh and the eighteenth, she purposely played mashie shots short of the greens which were guarded by dangerous hazards, when the more risky strokes of Miss Rosenthal entailed far greater danger in crossing the dreaded sand pits, and ultimately gained nothing, since both holes were halved. When it came to the last putt on the home green, an apparently innocent stroke of three to four feet that would not be difficult under ordinary circumstances yet the very stroke that is most often missed under such trying conditions, the champion never faltered and "sunk" her ball as truly as though the championship of America had nothing whatever to do with the direction of her putt.

Mrs. Jackson's play lacked the freedom of wrist and elbows that helped Miss Rosenthal to get such good length in her long strokes, but she timed her swing splendidly, and used enough follow through to keep her ball straight on the course almost all of the time. Her putting was exceptionally good, only one or two possible opportunities on the greens being lost, and her iron play was consistently fine throughout the week of championship play. Her good judgment and entire confidence however, stood out above everything else in the champion's play. She generally went ahead and looked at the line of play to gauge the distance to bunkers and traps when they were not in plain sight, and she selected her clubs for use without advice or consultation with caddy or friend.

In Mrs. Jackson we have a new champion who deserves her laurels and who wears them well.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now