Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

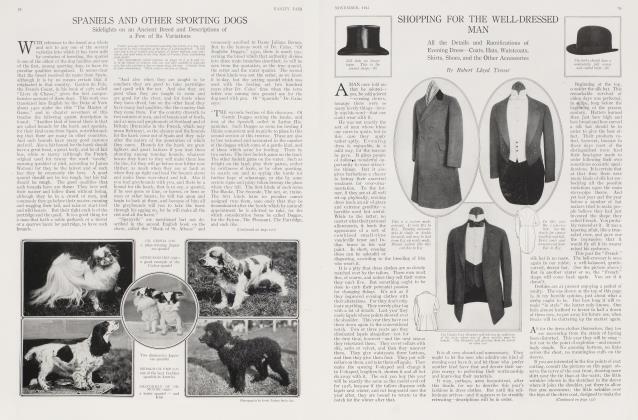

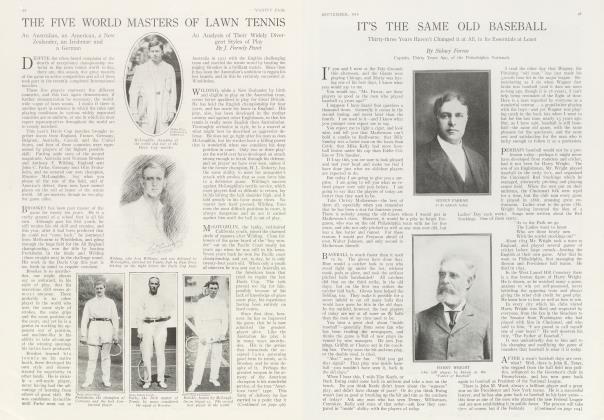

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowJOHNSTON, THE NEW NATIONAL TENNIS CHAMPION

J. Parmly Paret

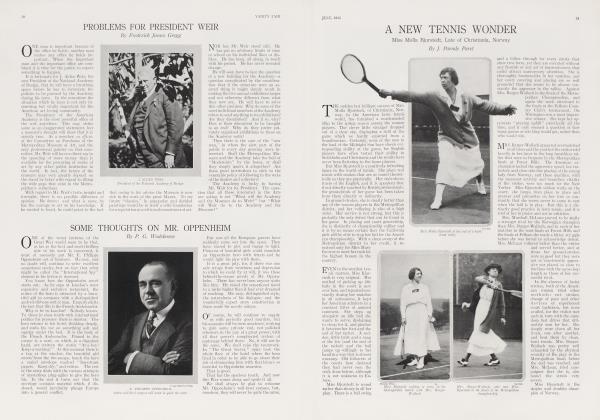

CALIFORNIA proved herself supreme in lawn tennis this season, making almost a complete sweep of the year's honors, and a new king of the lawn fell heir to the crown worn by Norris Williams when young William Johnston, of San Francisco, swept the courts at the recent championship meeting at Forest Hills.

Johnston is the youngest, smallest lightest, thinnest, most unexp cted national champion we have ever had, and he plays in the best form of any— with the possible though doubtful exception of Larned. He earned his title with a most complete victory over all his rivals.

A mere boy of twenty, the Californian made a poor record this season until he reached the championship meeting, and by the best critics was considered then to be a distinct outsider. He had been beaten by Theodore Pell, by Nathaniel Niles and even by Heath Byford, of Chicago, before he made his successful bid for the championship, and few could figure him out as even a "serious contender," to use the words of the Championship Tournament Committee, in its efforts to keep the entries for the meeting down to a field of reasonable proportions.

With perhaps the worst draw of any of the first-ten players of last year, Johnston went through the whole field, winning in succession from Harold H. Hackett, Karl Behr, Clarence Griffin, Norris Williams and Maurice McLoughlin. Williams was champion last year, McLoughlin for the two preceding seasons, and Behr was rated for 1914 as the third best player in America. So Johnston won from the three greatest players in the country in succession, and in each case there were heavy odds against him before he began his match.

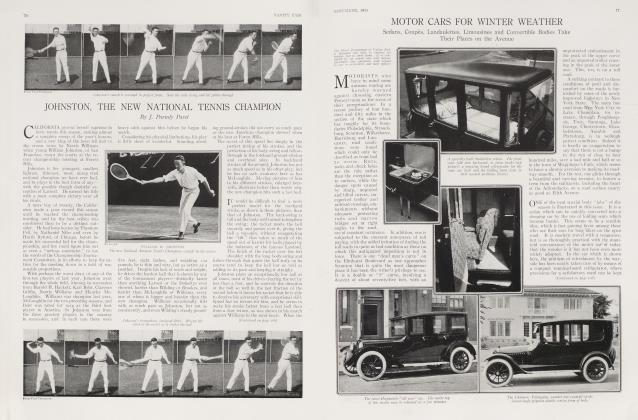

Considering his physical limitations, his play is little short of wonderful. Standing about five feet, eight inches, and weighing 120 pounds, he is thin and wiry, but as active as a panther. Despite his lack of reach and weight, he drives the hardest ball that is shown by any of the tournament players—distinctly faster than anything Larned or the Dohertys ever showed, harder than Wilding or Brookes, and harder than McLoughlin or Williams, every one of whom is bigger and heavier than the new champion. Williams occasionally hits with as much pace as Johnston, but not as consistently, and even Wilding's steady pounding ground-strokes did not carry as much pace as the new American champion showed when at his best at Forest Hills,

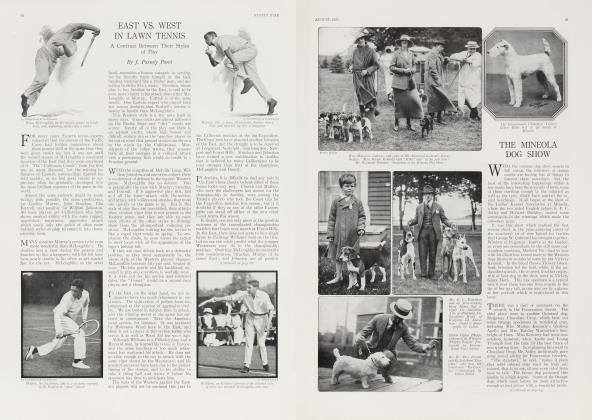

The secret of this speed lies simply in the perfect timing of his strokes, and the perfection of his body-swing and followthrough in the forehand ground-strokes and overhead play. In backhand strokes off the ground, Johnston has not as much speed as in his other play, but he has no such weakness here as has McLoughlin. Moving pictures of him in his different strokes, enlarged herewith, illustrate better than words why the new champion hits such a fast ball.

IT would be difficult to find a more perfect model for the forehand stroke, as shown in these pictures, than that of Johnston. The back-swing is full and the body well turned to lengthen the swing; the racket meets the ball squarely and passes over it, giving the ball a top-spin, without exaggerating the "lift" that takes so much of the speed out of harder hit balls played by the imitators of the famous Lawford. The finish of the racket over the left shoulder with the long body-swing and follow-through that guide the ball truly on its course tend to keep the ball low as well as adding to its pace and keeping it straight.

Johnston plays an exceptionally low ball at all times, most of his drives clearing the net by less than a foot, and he controls the direction of the ball so well in the last fraction of the second before it leaves his racket that he is able to deceive his adversary with exceptional skill. Speed has no terrors for him, and he seems to make his stroke better from a fast ball than from a slow return, as was shown in his match against Williams in the semi-finals. When the fifth set of this struggle was reached, the former champion was hitting very hard and many thought he would be able to head off his challenger by mere speed alone. On the contrary, Johnston came back stronger than ever in the last set, and answering speed with speed, clearly outmatched the great Williams at his own game.

(Continued on page 106)

(Continued from page 76)

IN the final match for the championship, in which the new champion faced the old champion, McLoughlin, the most spectacular play of the meeting took place. The score was 1-6, 6-0, 7-5, 10-8. In the first set, Johnston was over-awed, and in the second set, McLoughlin was over-confident, both passing into history in record time. Even the third went so quickly that only forty-five minutes had passed when three sets were finished.

But the last set took more time than all three of the others combined, and before it was over, both these trained athletes were so exhausted from excitement— not from fatigue, as the rallies were short and they had not been playing long; nor from the heat, as the day was comparatively cool and the sky overcast—that both staggered toward the end and sat down between games panting, a thing almost unheard of in even the hardest tennis matches. Many times McLoughlin was within a point of losing the match, only to pull out of danger again, and more than once he was within a single stroke of bringing the match even at two-sets-all. But it was not to be, and the great McLoughlin was finally worn down by the everlasting hammering of Johnston's terrific drives until the title changed hands and the new king was crowned.

Johnston's smashing was more in evidence in the doubles than in singles, as this is a stroke that is more often used in the double game. Like his service, the champion smashes in almost perfect form. There is none of the exaggerated swing that mark this stroke in the hands of many other players, but the ball goes away like a shot.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now