Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe New Crop of Tennis Youngsters

How Far Will They Go in Replacing the Veterans?

J. PARMLY PARET

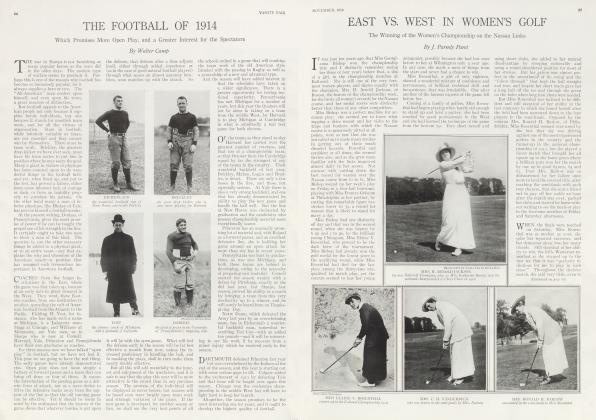

WE are entering, this season, a renaissance of lawn tennis that promises an entirely new order of things, not only in the United States, but in Europe and Australia also; for all old standards of the game were swept away by the war. The older group of players, which was dropping off fast when the war came, has almost disappeared, and a new school has sprung up to take its place.

Of the first ten players of 1914, 1915 and 1916 (there was no official ranking in 1917) practically all went to the war—in fact, war activities, of one sort or another, swallowed up nearly all of the better players of the country. Only a few of the veterans remained at home.

Remember, tennis appeals first to the most hardy specimens of the race, those who thrive best on excitement, and the "great adventure" appealed to their nature. It was not surprising, therefore, that few of those whose special equipment of red blood made them successful in tennis, should have failed to answer the call to the colors, for few activities promise more excitement than tennis, and war is one of these.

WITH Williams, Washburn, , Larned, Wrenn, Adee, Mathey, Armstrong, Bull, all in the army; with McLaughlin, Johnston and many lesser lights, all officers in the navy; with Church, Voshell, Griffin and Davis in the air service, the championship playing was left last year to Murray (who was engaged in chemical war work at home), Kumagae and the younger players.

At present all of the old men are fairly itching to get back into harness again, and Williams, Washburn, and some of the others, still martyrs to the good cause in France, have been getting occasional practice this spring at Cannes, Nice and Paris, but the real competition here has been so far left to the youngsters. This golden opportunity for younger America during the last year or so has not been wasted, for we have been developing a most promising crop of newcomers.

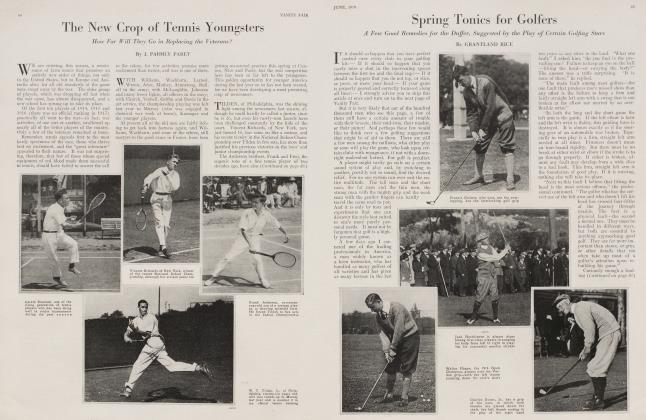

TILDEN, of Philadelphia, was the shining light among the newcomers last season, although he could hardly be called a junior, since he is 26, but even his newly-won laurels have been challenged constantly by the kids of the court. Vincent Richards, of New York, now just turned 16, has come on like a meteor, and his recent victory in the National Indoor Championship over Tilden in five sets, has more than justified his previous victories in the boys' and junior championship events.

The Anderson brothers, Frank and Fred, the eugenic sons of a fine tennis player of two decades ago, have also startled the older established champions by remarkable skill, but they both started in at a tender age to learn the game, as did Abraham Bassford 3rd and William D. Cunningham, sons of other veteran players, who have made good.

(Continued on page 86)

(Continued, from page 64)

Young Bassford, only 17, is small, while both of the Andersons are giants for their age, but all three are playing tennis already that promises wonderful things when their skill ripens, if they follow up the game. Frank Anderson, only 17, forced Tilden to the full five sets in the National Indoor Championship this spring before he was beaten, while Bassford has also shown some really fine streaks of play.

"Chuck" Garland, of Pittsburgh, is another son of an old player, who began to play when he could scarcely lift a racket and came into his own at a tender age. Young Garland is expected this season to rank up close behind the first flight of experts, although his lack of speed limits his possibilities. Gerald Emerson is also coming on fast, and crowding for a place among the leaders.

WHETHER or not the older men, Williams, Washburn, Murray, Pell, Church, Kumagae and the others of previous seasons will be able to hold this new crop of youngsters safe, is the biggest problem of the season. Opinions differ, but I fancy they will, if for no other reason than the power of old heads over young hearts and arms.

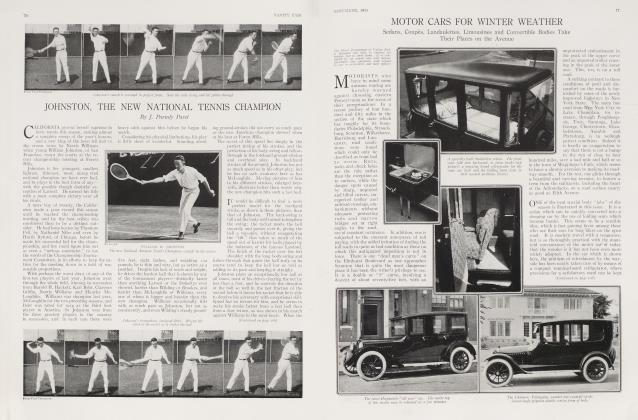

The great handicap from which the "boy wonders" suffer is inexperience. This, offhand, seems to be a very trite comment, but it is not so shallow as it might be. Youngsters to-day seem more headstrong, more difficult to teach the finesse of the experienced player than those of by-gone days. They play the game better in many ways, but they are slower to mature and ripen by experience. We have had infant prodigies in tennis before, it must be remembered. "Ollie" Campbell was a champion at 15. Malcolm Chace was the "Providence boy wonder" before he was 16, and Bob Wrenn, Leo Ware, Malcolm Whitman and others, all won spurs in major tournaments at tender ages.

But the youngsters of the older days learned more thoroughly than those of this generation. Our boys of to-day hit the ball much harder, serve better and kill lobs better—all their mechanical execution is better—but they lack the variety of play, the finesse and subtle skill of headwork more than did those of twenty years ago.

ONLY a few years back, we had another sample of this in Harold Throckmorten, the youthful interscholastic champion. He hit the ball with tremendous speed and played good-tennis, but he lacked the headwork to make him a really great player, and the "heady" older men generally beat him by their greater experience.

Comparing the actual playing skill of the boy champions of to-day with the leaders of ten years ago and twenty years ago, it seems clear that the game steadily progresses along lines of speed and technical execution, but the playing lives of the leaders seem so much shorter that youthful skill seldom ripens into maturity, and we see much fewer cases of good court generalship. There is a whirlwind of slam-bang that would carry the older men off their feet, perhaps, and a service that is very difficult to handle, but nowhere such placing of the service as Harold Hackett's, no such deadly net attacks as Holcombe Ward's or George Church's, and no such fine passing as W. A. Larned's.

RICHARDS is perhaps the best of the really young players, but it is very doubtful if he could stop the more experienced headwork of the older leaders of just before the war. Williams, Johnston and Murray, for instance, should at their best, all be able to hold the youngsters to-day with a safe margin. If we go back ten years, and take the standard of that decade, again we find the boys of to-day not yet ripened to their skill, while it seems almost as certain that the greater generalship and court tactics of Beals Wright, Holcombe Ward, Malcolm Whitman, William Lamed and other leaders of twenty years ago, would more than offset the harder hitting of the new generation.

BUT we must concede the tremendous advance in the service, and of clean, hard hitting—the technical skill of the boys. They have made rapid strides forward and the ball now travels faster and often with more precision and length than a few years ago. And there are ten good ones to-day where but one shone before. If we could but teach these boys some generalship, some finesse, what wonders they would be!

Richards, for instance, is as cool as a veteran under the stress of fast play and makes fewer errors in technical execution of strokes. But he lacks the ability to plan a campaign, the knowledge of when to go to the net, and the judgment of strokes to use in different emergencies, which experience brings to brilliant youngsters only when they are willing to learn such tactics from older players whom they can often beat.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now