Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Most Startling Moderns Are to Be Shown in New York This Winter

January 1915 F. J. G.NEW YORK is now, for the time being at least—the art capital of the world, that is to say, the commercial art centre, where paintings and sculptures are viewed, discussed and purchased and exchanged.

Many predictions had been made, from time to time, as to when this state of affairs would come about. For years the drift of "old masters" has been Westward. Dr. Bode of Berlin, and other experts, had talked about the danger represented by the American buyer as competitor, in the open market, with the public galleries of Europe, limited as the latter were by slender resources and the niggardliness of parliaments. The London National Gallery and the Louvre have envied and feared the mighty resources of our Metropolitan Museum, which enabled it, at any moment, to pounce on whatever might emerge from private ownership—whether it was a newly discovered Rembrandt or a hitherto unsuspected collection of Chinese porcelains. So, while England, or France, was appealing to the patriotic to subscribe in order that some treasure might be kept from making the Atlantic voyage, word would come suddenly that the worst had happened, and that the dreadful Americans had scored again, thanks to the Rogers bequest or the alertness of some private benefactor.

The Great War—which has affected everything and everybody—hastened what prophets regarded as inevitable. Paris, London, Berlin and Petrograd, having the grim necessity of national sen-preservation to attend to, simply went out of business as far as "art" was concerned.

The young painters and sculptors, like the young men in the picture-shops, are with the Colors. The exhibitions are all off'. Hundreds of studios are locked up, and the cafes where the quarrelsome geniuses took their meals, and their ease, are but sad and quiet resorts of the casual and careless sightseer.

THIS is where technically neutral New York arose to her opportunity. For a while everything was up in the air, like Wall Street. But through patience and perseverance the tangle was straightened out. So the six weeks' Matisse exhibition, planned to take place in the Montross Galleries in January, has become an assured fixture, and the set of exhibitions of the men of the younger French school at the Carroll Galleries will occur in the winter months just as if Europe, instead of being convulsed from one end to the other, were wrapped in profound peace. It is to be hoped that not many of the paintings will have to be hung with the customary purple.

New York will see, at the Matisse show, what the most discussed of all the Moderns regards as his most important, because most significant, work.

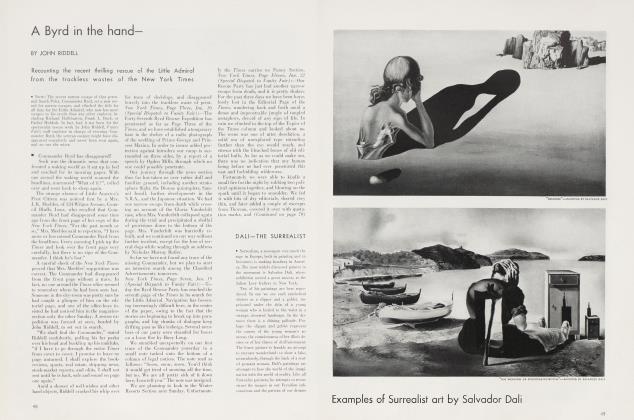

In the ultra Modern exhibition, at the Carroll Galleries, will be seen the work of Gleizes, Jacques Villon; Derain, painter of the "Fenêtresur Parc;" Redon, of the humming flowers; Chabaud, of the "Flock Leaving the Barn;" de Segonzac, Dufy, de la Fresnaye, Moreau, Marcel Duchamp, who staggered New York with his "Nude Descending the Stairs;" Rouault Picasso in his successive "red," "blue," and "cubist" periods; de Vlaminck, Signac, Seurat, and Duchamp-Villon. There will also be total strangers to us like Vera, Valtet, Ribemont-Desseignes, Marc, Sala and Jacques Bon. In addition, the veteran impressionist master Renoir will make his bow to the public as a sculptor, with a figure in the round and a plaque.

One striking thing about the "new men" is the way in which the change from one medium to another, as Picasso and Jacques Villon with their etchings, Dufy with his wood engravings, Vera with his wood cuts and Mare with his book bindings. Perhaps, as far as our own artists are concerned, one result of the display of the creations of these Frenchmen will be to cause them to show what they have been doing in unexpected directions. The wood carvings of Arthur Davies and the wood engravings of Walt Kuhn would astonish most of those who are not familiar with the very private activities of these two artists.

THERE has been more quarreling about Henri Matisse than about any other individualist of our epoch. If Matisse were not convinced of his genius, he might well be reassured on the subject by listening to the shouts of "Impostor!" "Rogue!" "Knave!" with which he is greeted by those who don't like him. But this solid artist, who looks more like a professor of biology than a painter, is quite undisturbed by such popular clamor. If it is dishonest to paint without regard to the rules, he is content to be considered dishonest. But—great virtue in your "but"— nobody knows where your blessed rules are to be found, not even the learned creatures who talk so much about them.

Matisse does not care whether or not they call him a charlatan. He considers his art perfectly sincere and simple. Take his method of etching a portrait. Days are taken up in observation of his subject. Then he sets to work rather elaborately. The result is put aside. The second attack shows still less detail. In the final effort—that for which the rest was but preparation—every non-essential has been eliminated—nothing is left but something which suggests rather the qualities than the externals of his model. In a word— even if such a comparison is dangerous— Matisse develops a work from the heterogeneous to the homogeneous, from the complex to the baldly simple.

He has obtained less recognition at home than abroad, though Marcel Sembat, the present Minister of Public Works, and, since the death of Jaures, the chief socialist leader, is an ardent collector of his works. On the occasion of his first exhibition at Willard's, the preface of the catalogue was written by no less official a person than Roger Marx, the editor of the "Gazette dcs Beaux Arts." The fact that the dealer wanted to give greater prominence to the critic than to tinpainter caused a disturbance which had true farce-comedy features. But Matisse won on points.

The following proves nothing. But facts which are inconclusive, logically, are often interesting. Many of the Rembrandts, for instance, now in the Altman collection which is the most gorgeous possession of our Metropolitan Museum were, some years ago, the property of Alphonse Kami. He got tired of "old brown varnish" people will get tired of everything, no matter how classical and to-day he buys only Matisses. One of his proudest possessions is the nude, "with the blue leg," a painting which, shown in the International Exhibition of 1913, surprised New York, disgusted Chicago and horrified Boston. Still M. Kami, if he felt it necessary to defend himself from the sneers of the scornful, might point out that Matisse is safely enshrined, through his drawings in the French Museums; that other drawings, in spite of the notorious and aggressive conservatism of the Kaiser, are in the Print Cabinet at Berlin, and that he is more sought after by German collectors than any of the other "new" Frenchmen. Two characteristic paintings of prime importance, which will be seen in the Montross exhibition are the "Woman at a Desk" and "The Gold-fish." These are the property of a Moscow collector. As, owing to the war, it was impossible to send them to their owner, Mr. Matisse decided, after some urging, to allow them to come to America, provided they didn't go further West than New York.

SOON after the war broke out Matisse lost all trace of his mother, his brother and his brother's family, who lived at his birthplace, Le Cateau, in the Nord. For months he could not work. He went to his country home, from which he was recalled to Paris to make selections for his New York exhibition. This took his mind off his family troubles. By this time he is probably in active service, for, in spite of his rheumatism, he was determined to get to the war. If he envies a soul in the world it is the painter Derain who went out in the artillery, was wounded, returned to Paris, and has now gone back to the trenches.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now