Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

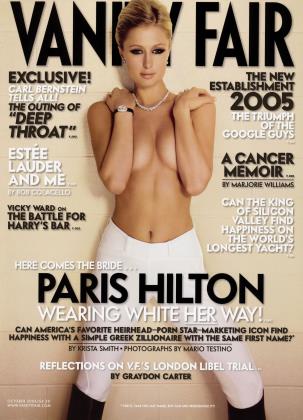

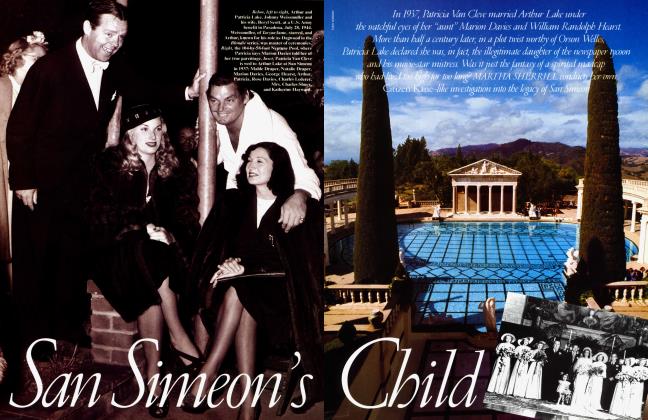

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhen Estée Lauder died last year at age 97, she left a hole in the power fabric of New York, a $10 billion beauty empire (including Clinique, MAC, and, now, Tom Ford's new line), and a close-knit dynasty to carry on her dream. Remembering his encounters with "the world's greatest saleswoman," and talking to her heirs, BOB COLACELLO chronicles Lauder's rise from peddling her uncle's face creams to art collecting and philanthropy

October 2005 Bob ColacelloWhen Estée Lauder died last year at age 97, she left a hole in the power fabric of New York, a $10 billion beauty empire (including Clinique, MAC, and, now, Tom Ford's new line), and a close-knit dynasty to carry on her dream. Remembering his encounters with "the world's greatest saleswoman," and talking to her heirs, BOB COLACELLO chronicles Lauder's rise from peddling her uncle's face creams to art collecting and philanthropy

October 2005 Bob ColacelloGovernor Pataki declared her "one of the giants not just of this great city but of the world." Mayor Bloomberg compared her to the inventor of the telegraph, Samuel Morse. Marvin Traub, the former head of Bloomingdale's, said, "She revolutionized an industry and was without a doubt the world's greatest saleswoman." For Barbara Walters she was a proto-feminist: "She turned 'No, you can't' into 'Yes, I will.'" As her onetime corporate lawyer Richard Parsons, the chairman of Time Warner, put it, "I never met a woman with more force."

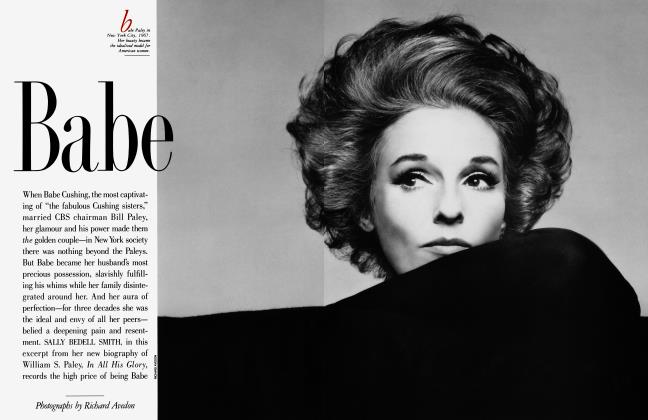

The lady these speakers were eulogizing, at a memorial in New York City in May 2004, a month after her death, entered this world in 1906 as Josephine Esther Mentzer, the daughter of a Queens hardware-store owner, and left it 97 years later as Estée Lauder, the creator of a $10 billion cosmetics empire. Probably the most successful and famous self-made woman of her time, she lived in grandly decorated residences in Manhattan, East Hampton, Palm Beach, London, and the South of France and counted the Duchess of Windsor, Princess Grace, and the Begum Aga Khan among her close friends. Brilliant, driven, and a master of using social connections to push products, she had started out emulating Elizabeth Arden, Helena Rubinstein, and Charles Revson of Revlon, but the business she founded had long surpassed theirs, and unlike them she had established a dynasty: two more generations of Lauders dedicated to keeping the company that bears her name No. 1 in quality fragrances and cosmetics. A year after the memorial, Lauder's granddaughter Aerin, one of the company's vice presidents, persuaded the hottest name in fashion, Tom Ford, to make his first post-Gucci venture a collection of beauty products called Tom Ford for Estée Lauder.

Estée's sons, Leonard, 72, and Ronald, 61, and all four of her grandchildren—William, Aerin, Gary, and Jane—also spoke at the memorial, a two-hour extravaganza held at Lincoln Center's New York State Theater. Skitch Henderson led the New York Pops in a medley of Estée's favorite songs as invited guests filed in—Alma Powell, the wife of then secretary of state Colin Powell; Libby Pataki; former ambassadors William Luers, Edward Ney, and Donald Blinken; New York Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr., Advance Magazine Publishers heads S. I. and Donald Newhouse, and Washington Post heiress Lally Weymouth; bankers Ezra Zilkha and Donald Marron; designers Oscar de la Renta and Carolina Herrera; billionaires Alfred Taubman, Jerry Speyer, and Gustavo Cisneros; grandes dames Kitty Carlisle Hart, Liz Fondaras, and Casey Ribicoff; virtually the entire boards of the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Modern Art (which are chaired by Leonard and Ronald, respectively); and 2,500 impeccably outfitted, coiffed, and made-up employees of the Estée Lauder Companies Inc.

"She was our mother, boss, and colleague—in that order," said Leonard Lauder. Jane Lauder recalled her grandmother's fondness for chocolate-covered marshmallows, which she ordered by the case from a company on Long Island and offered to family and friends at every opportunity. "If we always listened to her wishes," said Gary Lauder, the only grandchild not involved in the family business, "we'd all weigh 300 pounds and be all bundled up even on the hottest day of summer."

"She loved to cook, and she always cooked with her hat on, a purse, and blush," said Ronald Lauder. "Her specialties were onion rings, French toast, the best chicken soup, and a special spaghetti sauce that required about a half-pound of sugar. As a child, the thing I dreaded most were the parent-teachers conferences." He went on to tell the story of his mother's meeting with his English teacher, who eschewed makeup, kept her hair in a bun with a net, and always wore dark dresses with heavy black stockings and shoes. "The next morning," Ronald said, "I and the rest of my English class were stunned when our teacher walked into the classroom. Her hair had been done, her face was completely made up—including blush—and she was wearing a flowered-print dress with nylon stockings and high heels. When I asked my mother about it after school, she denied that she had anything to do with this transformation."

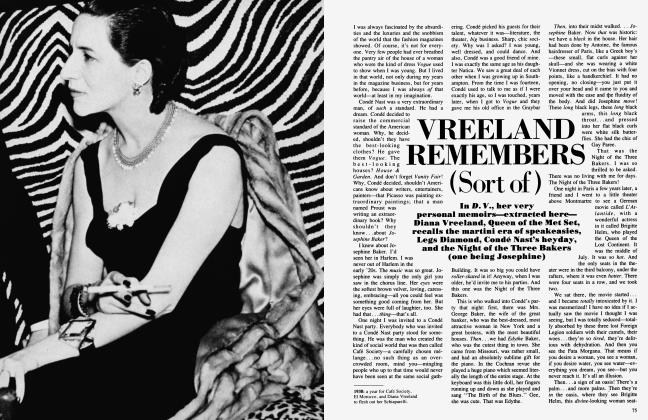

In the 1970s, when I started working at Andy Warhol's Factory, as editor of Interview, Estée Lauder was one of the three reigning divas of the New York fashion world, along with Diana Vreeland and Eleanor Lambert. Vreeland, the eccentric former Vogue editor in chief who ran the Metropolitan Museum's Costume Institute with an iron hand and an army of rich-kid volunteers, was the undisputed Empress of Fashion; Lambert, the peripatetic publicist who controlled the Coty Awards and the International Best-Dressed List but pretended she didn't, was its turbaned Queen; and Lauder, a few years younger than her septuagenarian cohorts and not yet widowed, was the Duchess with the Mostest. She had the power of the purse: with the Estée Lauder, Aramis for Men, Clinique, and Prescriptives brands, her company probably spent more on advertising than any other fashion or beauty business. As she once told me after I started working at this magazine, "Si Newhouse is one of my best friends. Seventeen million a year in advertising—of course he's one of my best friends."

As the wild, creative 70s gave way to the money-minded, formal 80s, Estée reached her social and business apogee. Her conservative, matronly style—she dressed mainly in couture from such established Paris designers as Hubert de Givenchy and Marc Bohan of Dior—was in keeping with the sedately glamorous look favored by Nancy Reagan, and she was very much part of the First Lady's New York inner circle, which included man-about-town Jerry Zipkin, Pat Buckley (the wife of the conservative columnist William F. Buckley Jr.), Cecile Zilkha, and the Herreras. Estée was one of the first to give a dinner for the new secretary-general of the United Nations, Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, and his wife, Marcella, in 1982.

I remember the supercritical Zipkin speaking admiringly of her over lunch at Le Cirque. "You have to give Estée a lot of credit," he said, "because she learned. She didn't always know how to do things the right way, let me tell you." He proceeded to describe the first dinner party he attended at the Lauder house, in the early 1960s: the maids, he said, wore black-and-white sneakers with their starched European-style uniforms, because Estée hated the click-clacking of leather heels on her marble floors; the tablecloth was crocheted; the main course was individual sirloin steaks. "Everything was wrong, wrong, wrong," Zipkin concluded. "But she was willing to listen and learn. And now, when you go there, everything is perfect."

By 1982, Estée Lauder Inc., headquartered in the General Motors Building, on Fifth Avenue, was the largest privately held cosmetics company in the world, with 10,000 employees and annual sales of more than $1 billion. Leonard Lauder had been president for a decade and would be made C.E.O. that year; his wife, Evelyn, the corporate vice president, was very involved in the development, packaging, and marketing of such new fragrances as White Linen and Beautiful; and Ronald, who oversaw the company's international operations in 80 countries, was up for an appointment in the Reagan administration. Roy Cohn, Estée's personal lawyer and friend, told me that she was apoplectic when she learned of the first post her younger son had been offered. "Who in Washington wants my Ronald dead?" she shouted to Cohn over the telephone. "Estée, what are you talking about?" asked Cohn. "They want to make him ambassador to Jamaica," Estée replied. "My friend Sarah Spencer-Churchill was raped in Jamaica! My Ronald is not going to a crazy country like Jamaica."

"She was our mother, boss, and colleague—in that order," said Leonard Lauder.

In 1983, Ronald went instead to Washington as deputy assistant secretary of defense for European and NATO policy, and Estée started sending his boss, Caspar Weinberger, a box of chocolate-covered marshmallows every week.

That same year Estée lost her husband, Joe, who had founded the Estée Lauder Cosmetic Company with her in the 1940s and was in charge of its finances and manufacturing plants until Leonard took over in 1972. The 80-year-old Joe, a good-looking, quiet man who never seemed threatened by his wife's celebrity, collapsed after a family dinner on the couple's 53rd wedding anniversary. It was a loss from which the seemingly strongest of women would never truly recover.

Joseph Lauter, who like Estée was a child of immigrants from Central Europe, was a partner in the Apex Silks company when they married, in January 1930. The newlyweds moved into an apartment on West 78th Street, Leonard was born three years later, and somewhere along the way Joe's family name was changed to what Estée claimed was the original European spelling. As the Great Depression set in, the silk company failed, as would a series of garment-center ventures Joe became involved with later in the 1930s. Estée, whose energy matched her ambition, decided to go to work. She briefly tried to act, but, she admitted, "I was not destined to be a Sarah Bernhardt, even though I did have a retentive memory."

Since high school she had been fascinated by the skin creams made by her uncle John Schotz, a Hungarian-born chemist, and loved watching him mix his Six-in-One Cold Cream and Dr. Schotz Viennese Cream (not to mention his poultry-lice killer, freckle remover, and Hungarian Mustache Wax). Now she started selling his creams at Hadassah luncheons, Borscht Belt hotels, and middle-class Jewish beach clubs on Long Island. With her svelte five-foot-four figure, eager hazel eyes, and smooth, clear complexion, Estée was hard to resist, especially when she started giving her customers free samples of a product they hadn't bought—thus inventing what would become the industry-wide marketing practice known as "gift with purchase." With her career taking off, and Joe's stalled, their marriage floundered. "I was not only moving farther ahead than he, but I was doing so in a world he did not share," she later explained. "I did not know how to be Mrs. Joseph Lauder and Estée Lauder at the same time."

In 1939 they divorced, and Estée began spending much of her time in Miami, selling her uncle's products in a shop at the Roney Plaza Hotel. Among the men she dated during this period was A. L. van Ameringen, a leading manufacturer of the essential ingredients used in perfumes, cosmetics, soaps, soft drinks, and candies (whose New York-based company, after a 1958 merger with a major European competitor, would be known as International Flavors and Fragrances, Inc.). By all accounts, Estée was infatuated with the distinguished, Dutch-born tycoon, and some say she lived with him for a while, even though he was married. His daughter, the late Lily Auchincloss, once told me that her father and Estée had been romantically involved, but that he encouraged her to go back to her husband when Leonard contracted the mumps, and he saw how close she and Joe still were in their shared concern over the boy's health.

Joe and Estée remarried in 1942 and had Ronald a little over a year later. Joe put aside his business for hers, and the couple set up a "factory" in a former restaurant on Central Park West, where they literally cooked the first Estée Lauder line on the restaurant's gas stove. In addition to four products adapted from her uncle's formulas—Super-Rich All-Purpose Cream, Cleansing Oil, Skin Lotion, and a masque called Creme Pack—Estée came up with a powdered rouge she called Glow and a lipstick named Just Red. The color of Dr. Schotz's medicinal jars—white with black covers— was replaced by "a fragile, pale turquoise," which Estée reasoned "would look wonderful in any bathroom."

The new company started off with a single retail outlet, the House of Ash Blondes, a beauty parlor on East 60th Street. Joe kept the books, Leonard made deliveries on his bicycle before school, and Estée added salons around the city, primarily by showing up unannounced and re-doing the proprietress's makeup with her own hands. ("Touch your customer and you're halfway there" was one of her mottoes.) Before long she had cracked her first department store, Bonwit Teller, where she spent Saturdays making up women at her counter on the main floor. In 1946 she received her first order from Saks Fifth Avenue, for $800; it sold out in two days, mainly because she sent out cards to the store's entire customer list offering a free lipstick with every purchase. So many women showed up that Estée was able to persuade the president of Saks to move her counter from the rear of the store to just inside the front door.

When she decided to introduce a fragrance in the early 1950s, she went to see her old friend A. L. van Ameringen, who provided her with the scent that would make her empire: Youth Dew. According to Lily Auchincloss, her father had remained fond of Estée, and he saw Youth Dew, which he considered a surefire hit, as his belated breaking-up present. But it was Estée who came up with the name, the mildly risqué ads featuring a blurry rear view of a nude woman, and the idea of packaging the heavy, vanilla-based scent as a bath oil that doubled as a perfume, because, she said, women waited for men to buy them perfume, but would not hesitate to buy a bath oil for themselves. Introduced in 1953, Youth Dew brought in $50,000 that year, more than doubling the company's total annual revenue. Three decades later, it was still Estée Lauder's best-seller, generating about $150 million annually.

In the spring of 1983, a few months after Joe Lauder's death, Estée asked me to accompany her to a party at Bloomingdale's. I was slightly thrown when we stepped out of her limousine and, as the paparazzi zoomed in on her, she told me, "Hold my bag." I have never quite figured out why she preferred to pose with her hands clasped in front of her, but hiding her pocketbook behind my back as we entered a department store or ballroom always seemed a small price to pay for the pleasure of her zany but cozy company. I had just quit my job at Interview and wasn't quite sure what I was going to do next, so Estée's first invitation was much appreciated. My night was made when we stepped off the escalator, Estée first, with me three feet behind. Who should be standing there but my former boss, Andy Warhol. "Gee, Bob," he asked, "are you Estée's date?" I nodded yes. "Oh, God, can you ask her for some ads for Interview?" I was only too happy to remind him, "I don't work for you anymore, Andy."

Estée next asked me to escort her to a charity ball at the Plaza hotel. A moment after we sat down, she noticed Queen Elizabeth's sister, Princess Margaret, at the next table. "Oh, my God," she said, "I have to go over and talk to her. She's a customer: Clinique." She jumped up, wrapped the pink tulle shawl that matched her pink satin ball gown around her shoulders, and headed for the princess's table. Within a few seconds, after tapping Her Royal Highness on the shoulder—something that's just not done—Estée was crouched down in front of Margaret with pen and pad in hand, taking her order. "Thank God I went over there," she told me when she returned to our table. "She's out of everything."

Meanwhile, Estée's shawl had gotten twisted up. "This thing is driving me crazy," she said. "It won't stay nice and smooth. Come with me." I followed her to an empty area at the side of the ballroom. "Now, you take one end and I'll take the other," she said, "and we'll get it untwisted once and for all." Just then, the costume jeweler Kenny Jay Lane passed by on his way to the men's room. "Doing laundry, girls?" he asked.

Unlike Elizabeth Arden, Helena Rubinstein, and Charles Revson, Estée established a dynasty.

After two nights out with Estée, I had realized the obvious: she was always working, and very few people even tried to stop her from getting her way. One night Gloria Vanderbilt, the heiress with the trademark Kabuki look, and I ran into each other as we were leaving a party at a Fifth Avenue town house. "May I hide behind you?" she asked, when we were outside, standing in a crowd of partygoers waiting for their cars or taxis. "Why, Gloria?," I asked. "Because there's Estée," Vanderbilt explained, "and if she sees I don't have a ride, she'll force me into her limo and then whip out her brushes and re-do my makeup. She's been trying to get me for years."

Estée's aggressiveness, however, was not entirely promotional; it was also her way of connecting with people. One day she and I were lunching at Mortimer's with a half-dozen friends when, much to my surprise, a birthday cake appeared for me. "You didn't tell me it's your birthday," Estée said, clearly annoyed. "I didn't tell anyone. I don't know who found out," I said. "Well, I've got to go," she said, leaving before coffee was served. When I arrived home less than an hour later, my doorman told me, "Estée Lauder just dropped this off for you." It was a shopping bag from T. Anthony, the Park Avenue luggage shop, containing a black leather briefcase just like the very worn one Estée had seen me carrying at lunch.

In 1985, in an attempt to overshadow the publication of an unauthorized biography, by Lee Israel, titled Estée Lauder: Beyond the Magic, Estée put out her autobiography, Estée: A Success Story. In her version, her father, Max Mentzer, had been "a Czechoslovakian horseman, an elegant, dapper monarchist in Europe, who, when transported to a new country, still carried a cane and gloves on Sundays." What's more, "Emperor Franz Joseph wanted his niece, who weighed about 300 pounds, to marry him, but somehow Father got out of that." His hardware store on Corona Avenue in Queens, Estée implied, was more or less a sideline to his real-estate investments. Her mother, née Rose Schotz, "was very fair, very delicate, and she was never seen outside without her gloves" or her big black umbrella with "an intricately carved silver handle," which she used like a parasol "to shield her from the sun." She "took the 'baths' religiously," first at Carlsbad and Baden-Baden in Europe, later at Saratoga Springs, New York, where little Estée accompanied her and was "vastly impressed." She made no mention of Corona's predominantly working-class Italian population or its many garbage dumps, which Lee Israel noted "smelled horrifically" and may have had something to do with Estee's attraction to the fragrance business.

When Estée's book came out, I was writing celebrity profiles for Parade, and the Sunday supplement's editor, Walter Anderson, assigned me to interview her. She received me in the all-red reception room of her palatial double town house, on East 70th Street off Park Avenue, wearing a red dress and hat. Her longtime public-relations aide, a white-maned Wasp matron named Rebecca McGreevy, stood beside her, and before I was allowed to turn on the tape recorder, Estée insisted that we "discuss what we're going to discuss."

"Did I ever imagine I'd live in one of the most magnificent mansions in New York?," Estée began. "I don't want to talk about my home. Did I ever dream I'd make so much money? Let me tell you from the start: we never mention money. I can tell you one thing. I did not get there by wishing for it, or dreaming about it, or hoping for it. I got there by working for it." She quickly dismissed her unauthorized competition. "It's nothing! Because she never met me. She never knew me or anything about me." Estée refused to confirm the date of birth on the certificate dug up by Israel, saying, "Glow is the essence of beauty, not age."

She then launched into a 45-minute monologue mixing biographical anecdotes, business maxims, beauty tips, product promotions, and teary-eyed reminiscences of her beloved Joe. An off-the-record tour of the house and its eye-popping art collection followed: "That's Klimt. That's Klimt, too. That's Kandinsky. This is my dining room, where I entertained the Duke and Duchess of Windsor many a time." In every room there were vases of red roses. "I think every man likes red," she said. "Have you ever noticed that European women wear a lot of red? Every time I wear red, a man flatters me. Red flatters. It's warm. That's why Cardinal Cooke always wore red. He looked so pure, so sincere, and so ethereal in red. I love red flowers, red lights, red everything."

The interview ended with a sales pitch. "What did you do to yourself today?" she asked, looking at me intently. "You look so handsome. You should always wear a light suit like you have on today, because it reflects the light and gives your face a glow. Did you ever consider using a bronzer? It's not makeup! We have a bronzer that is so thin you never know you have it on!"

A few days later I called to arrange to have her photographed for Parades cover. "Just tell them to use the beautiful picture on the cover of my book," she said. When I called her back and said that Parade preferred to have her shot by one of its own photographers, she snapped, "O.K., tell them I'm signing my book tomorrow at noon at my counter at Macy's. They can take my picture there." Walter Anderson then instructed me, "Tell her that the lighting is terrible at Macy's. We'll rent a studio around the corner." Estée showed up in a red-and-black outfit indistinguishable from the one she was wearing on her book jacket. The result was exactly what Estée had wanted: Parades cover and her book's cover were almost identical.

Nineteen eighty-six was Estée's annus mirabilis. In April, Ronald Lauder was named President Reagan's ambassador to Austria, the country Estée had often suggested was her birthplace. The appointment was not without its complications: Vienna was known for its excellent relations with the Palestine Liberation Organization, and Austria's freshly elected president, Kurt Waldheim, had been exposed as a former Nazi officer who had lied about his military record. The fact that Waldheim had been a regular presence at Estée's dinner table in the 1970s, when he was U.N. secretary-general, made matters even trickier for her son. But Ronald managed to distance himself from the tainted head of state while maintaining cordial relations with his government, and Estée repeatedly called the embassy to make sure he had not been kidnapped by the P.L.O. "I'm shaking in my shoes," she told friends, and the word around town was that she was paying for extra bodyguards. (The Washington Post reported that the State Department returned a $ 150,000 check from Estée for the embassy's entertainment fund.)

Three months after Ronald took up his diplomatic post, the Museum of Modem Art in New York opened its blockbuster exhibition "Vienna 1900: Art, Architecture & Design," which he had proposed in his role as museum trustee. Ronald had started collecting German Expressionist and Viennese Secession art as a student at the Goethe Institute, near Salzburg, in the early 1960s, and over the years his mother and brother had followed his lead. A large number of the works on display at MoMA were from the family's collections, and the exhibition was sponsored by Estée Lauder Inc. One night that summer the company hosted a cocktail party at the museum for its saleswomen from department stores around the country—"my girls," Estée called them. I accompanied her to the party, and as we walked through MoMA's galleries, she pointed out which Klimt and Schiele paintings she owned. "That's mine," she said. "Eight million insurance. That's mine—six million insurance." When we came to a small, dark Kokoschka portrait of a bearded man, she announced, "The boys made me buy it—three million insurance," and asked me what I thought of it. I said it was "a strong painting." "That's what the boys said. I've got a house full of strong paintings. What I need is a strong man."

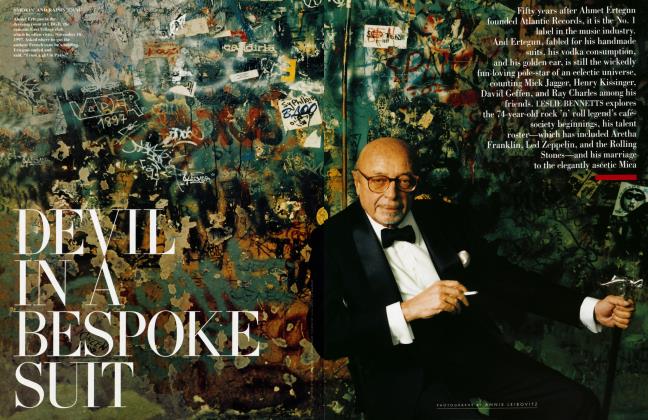

By the time the exhibition closed that October, Estée was riding as high as she ever would. With her sons and daughters-in-law as her co-chairs, she presided over a $1,000-a-ticket Hapsburg-themed Vienna Ball at MoMA, complete with white-wigged footmen, pheasant in lingonberry sauce, and Wiener Werkstätte-style gift bags containing the latest Lauder offerings, Beautiful (for women) and Tuscany (for men). The guest list was limited to 400, and among the attendees were Blanchette Rockefeller, Bill Paley, Henry Kissinger, the Buckleys, Ann and Gordon Getty, Lee Radziwill, and Malcolm Forbes. It was one of those occasions when the ladies took their big rocks out of their safes—on her command, according to Estée, who was bedecked in diamonds. "I called up all my friends," she told me, "and said, 'Wear everything, and what you can't wear carry.''"

The following December, I was seated next to Estée at the annual holiday lunch that she, Leonard, and Evelyn used to give for Condé Nast editors and publishers. It was held in the private room of Le Cirque, and the Queen of Cream was in fine fettle. She had S. I. Newhouse on her right, and she kept pushing petits fours and chocolate truffles in front of him, even though he kept pushing them away. Her speech was classic Estée—extemporaneous, earthy, hilarious. "Forty years ago," she began, "I went to see a Miss Peck at Vogue about getting some editorial coverage, and she suggested that I advertise. The only thing I could afford was the smallest ad in the back pages, so I took this very small ad and put a photograph of a naked woman next to a bottle of Youth Dew. And that little ad got so many letters from churches all over the country. The only thing I can say is I wish some of those priests were still alive to see where I am today." When the laughter died down, she added, "I always say, when sex goes out of business, that's when I'll go out of business."

From Vogue, she said, she moved on to Mademoiselle, where her first request for "editorial" was also turned down. "So I said to the editor there, 'Do you mind if I do your girls, as long as I'm here, with my products, which are the best in the world?' Because I noticed that all the girls at Mademoiselle in those days had bad skin—clogged pores. So the editor said O.K., and I started doing these girls' faces, and when they saw how beautiful they looked, and that their pores weren't clogged anymore, they started giving me so much editorial that Mr. Revson called the editor and said, 'Why are you giving this Estée Lauder so much editorial when she doesn't even advertise?"'

I spent the next two years holed up in Rhode Island writing a book about Warhol, so I missed most of the hoopla surrounding Ronald Lauder's run for mayor of New York City in the 1989 Republican primary against the then U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, Rudy Giuliani. Prodded by Estée, I did make it to a Lauder-for-mayor fund-raiser at the Plaza hotel, along with a remarkable number of tycoons and socialites, including Henry Kravis and his then wife, Carolyn Roehm, Saul and Gayfryd Steinberg, Alfred and Judy Taubman, and Carroll Petrie. Much to the amusement of Estée's Park Avenue pals, every speaker made a point of mentioning that the candidate's mother was from Queens, and Estée, in a pillbox hat with a little veil, would nod and smile as they said it. Although Ronald spent $14 million—more than any other mayoral candidate ever had—on a campaign that was advised by Roger Ailes, run by Arthur Finkelstein, and supported by Senator Alfonse D'Amato, three of the five county leaders, and Rupert Murdoch's New York Post, he was trounced two to one by Giuliani, who then barely lost to Democrat David Dinkins in November. "Estée was not crazy about him running," recalled one family friend, "but she went along with it, because she never said no to Ronald."

The last time I saw Estée was in 1993, when she was 86 and beginning to slip into the long decline of her last decade. I had recently returned to New York after two years in Paris covering the European scene for this magazine and had bought an apartment on East 70th Street. One spring afternoon I was rushing to Lexington Avenue when I ran into Estée, dressed up and made up, taking some air in front of her house with a maid and a security man. "Estée," I said, "how are you?" She seemed unsure of who I was, so I raised my voice and said, "It's me. Bob Colacello." "Oh, you," she said. "You used to be my boyfriend, and now you never call, you never write." "I've been living in Paris," I explained. "What's the matter," she snapped. "They don't have phones in Paris?"

Within a year or so, she was a virtual recluse in a wheelchair. Apart from her family and servants, the only person who saw her regularly was Lou Gartner, a retired House & Garden editor from Palm Beach whom she had known since the 1970s. "I went up to New York every other month for a week for nine years," he told me. "Until she died. She was very with it at first, and she was so funny. We used to have Saturday lunch in the dining room, and I arrived one Saturday wearing a cashmere sweater and corduroys. She looked me up and down and said, 'Where are you going dressed like that?' I said, 'Estée, you gave this sweater to me.' She said, 'O.K., sit down.' In the beginning, the boys would hire a musician who would come in with a portable piano and play show tunes, and she sort of sang along. But then that stopped. The last years all I did was spend a week holding her hand. She stopped talking. We had a system where she squeezed my hand once for yes, twice for no."

Other old friends grumbled about not being able to get through to her. "If she wanted to see someone," Gartner says, "she would have seen them. She drew the blind. She'd had it. She'd seen everything she wanted to see and she'd done everything she wanted to do."

Was she happy?

"Happy, I don't know. Maybe content."

According to Ronald, most days she had "a few good hours," and the family would take turns visiting her. "My mother never really changed," he told me. "You know, whenever I'd tell her I'd seen one of her old friends—São Schlumberger, let's say—she wouldn't ask me how they were. She'd ask, 'How does she look? Is she still so pretty? Is her skin still so beautiful?"'

All the while, the family business thrived. In November 1995, Estée, Leonard, and Ronald, who each owned one-third of the company, sold 13 percent of their shares to the public for about $340 million, while retaining about 91 percent of the voting rights for themselves. Leonard told Newsday that his mother had to be talked into giving up even that amount of family control. According to Gartner, "Her whole attitude was: Let them do what they want to do."

With the fresh infusion of cash, the company went on a buying binge, acquiring for the first time brands created outside its own laboratories, including MAC, Bobbi Brown, Aveda, and Stila, and making deals to produce and distribute cosmetics lines for such big-name fashion designers as Tommy Hilfiger and Donna Karan. In 1998, Forbes estimated that, despite Ronald's substantial losses in starting up a Central European media network, the Lauder brothers had a joint net worth of some $6.4 billion. There were notable achievements outside the business sphere as well. Paralleling Ronald's rise at MoMA, Leonard became chairman of the Whitney's board in 1994; in 2002 he and several other trustees gave the museum 87 modern-art works valued at $200 million. The previous year, Ronald's Neue Galerie, showing German and Austrian art, had opened on Fifth Avenue to critical accolades and long lines. Evelyn Lauder's Breast Cancer Research Foundation, which she established in 1993, emerged as a leader in its field and is probably one of the few charities to have been supported by both the late Diana, Princess of Wales, and Prince Charles's Prince of Wales Foundation. Jo Carole Lauder, Ronald's wife, is chairman of the Foundation for Art and Preservation in Embassies, having succeeded its founding chairman, Lee Annenberg; most recently FAPE has commissioned site-specific works by Louise Bourgeois, Ellsworth Kelly, and Martin Puryear for the new U.S. Embassy in Beijing and by Sol LeWitt for the new U.S. Embassy in Berlin.

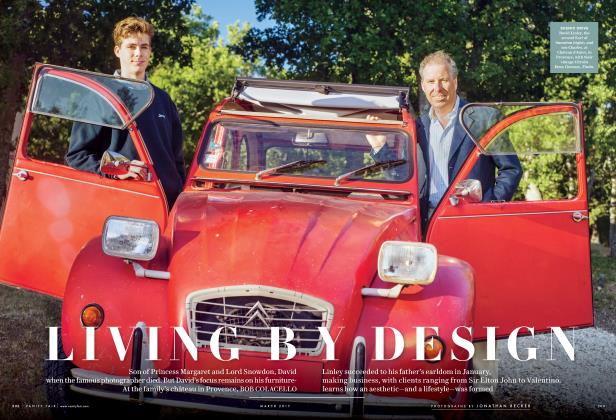

During the summer immediately following Estée's death, the company announced three promotions: William Lauder, the elder son of Leonard and Evelyn, was named chief executive officer; Aerin Lauder, Ronald and Jo Carole's elder daughter, became senior vice president of global creative directions for the Estée Lauder division, which reportedly still accounts for about 35 percent of overall revenue; and Jane Lauder, Aerin's kid sister, was made vice president of marketing for Flirt! and American Beauty within BeautyBank, "a new division created to develop new brand concepts and global opportunities for the company."

"I think my grandmother would be very proud," William told me. "That would be my hope. Most importantly, we all enjoy working together." Although his father remains chairman and his mother senior corporate vice president for fragrance development, William, 45, is responsible for the day-to-day operations of the company. Like his father and uncle a graduate of the Wharton School of Finance and Commerce at the University of Pennsylvania, he joined the business in 1986 and worked his way up the corporate ladder, becoming C.O.O. in 2002. He called his decision to follow in his father's footsteps "osmotic, having caught numerous conversations around the dinner table my whole life. When I was 13, I worked for the company for a few weeks before I went to camp, and I went on some business trips with my father. Then when I got more serious in college, saying this is perhaps something that's really going to be a career choice for me, my father said, 'Look, this is great. But you're going to go and do time elsewhere first.' So I went to work for Macy's for three years. I loved it."

The company could have lost its heir apparent to public service, however. After William spent a summer working for Secretary of the Treasury Donald Regan in the first Reagan administration, he recalled, "they made me a wonderful offer. They said, 'You're doing a wonderful job. Come back.' I just said, 'You know what? This is not where I see my career going.'"

Jane Lauder told me that she too felt the pull of the company early on. "My grandmother was so passionate about the business, and her passion and that of the rest of my family made it so exciting that you wanted to be part of it," she said. Still, after graduating from Stanford in 1996, she told me, "I wasn't ready to come back quite yet, so I spent a year working in advertising in San Francisco. Then I moved back to New York and started working in sales at Clinique."

The new BeautyBank division, Jane said, was "championed by William," and she worked closely with her cousin and other executives for a year and a half before its creation was officially announced, in 2004. "Our first project has been developing a whole beauty department for Kohl's," she said. The Milwaukee-based department-store chain, she explained, "had a little bit of private label they did themselves, but for the most part they were a $10-billion-a-year company with no cosmetics. So we launched three new brands last October at Kohl's—American Beauty, Flirt!, and Good Skin. For the time being, they'll be distributed exclusively at their 688 stores around the country. They're our brands, though, so we can take them around the world, and we're planning that for the future."

Of all the Lauder heirs, 35-year-old Aerin seems most like her grandmother. Her uncle Leonard told the New York Post several years ago, "I look at Aerin and I see Estée. She has her flair. She knows how to pick the exact right fragrance, the exact right color." Aerin also knows how to use a high social profile to burnish the company's image and promote its products. Estée put titled friends such as Princess Grace and Contessa Donina Cicogna Mozzoni on her scent advisory committee; Aerin's closest pals tend to have names like Lauren duPont and Renée Rockefeller and can be counted on to show up at product launches in department stores as well as at small dinners at her Park Avenue apartment, which is filled with works by such artists as Robert Ryman and Brice Marden.

When I asked Aerin if she knew as a child that she would end up working for the company, she answered without a moment's hesitation. "It's funny, because I really did. Everyone always says, 'Did you do anything first before you went into the company?' And I didn't. Every summer I worked either at Clinique or Prescriptives. After college I stayed at Prescriptives for about two years, and then I moved on to Estée Lauder. In the past, I was focused on advertising. Now I'm doing basically all creative, which entails advertising, store design, packaging, and merchandising.

"I used to love to watch my grandmother put her makeup on and get dressed," she continued. "She always used to wear these amazing pendants on a long chain, and I recently bought one for myself. What she did—you know, being able to balance the family and her career—is something that I really look up to."

Nine months after her promotion was announced—and nearly a year to the day after her grandmother died—Aerin was on the front page of Women's Wear Daily, along with the Estée Lauder division's president, John Demsey, flanking their latest star hire: Tom Ford. Demsey had negotiated Lauder's deal with Ford and his business partner, former Gucci C.E.O. Domenico De Sole, but it was Aerin who had first heard "from a very close mutual friend that Tom was interested in doing something with a beauty-and-fragrance company." She added, "We jumped at the opportunity."

Industry analysts agreed that it was just the kind of jolt that Lauder's aging namesake brand needed, and credited Aerin with pushing the deal through despite reported reservations on Leonard Lauder's part. By the April 12, 2005, signing, the family, as always, had pulled together, with William telling WWD that he considered Ford "one of the early-21st-century's stylemakers." Ford returned the compliment, saying that his grandmother had worn Youth Dew until the day she died and that he himself had been a big fan of Aramis bronzer as a teenager.

Aerin told me, "Tom is actually very similar to Estée, in that he understands his consumer, he has a passion for what he creates, and he likes to be provocative. So did Estée for her time: she ran a nude woman in her first ads; she was the first one to have jeans on a model; she was the first one to do a sports fragrance—Aliage—and now everyone does sports fragrances. Tom Ford is a lifestyle within himself. And so was Estée."

As she spoke, I remembered the first time I had sat next to her at a dinner party, in the early 1990s. She had just graduated from the University of Pennsylvania's Annenbeig School of Communications. Like Estée, she began our conversation with flattery, telling me she had liked my profile of the German fashion designer Jil Sander. "I love Jil Sander's clothes," she said. "They're so well designed and well made. It's all about quality, really—just like Prescriptives, where I'm working now. Our products are made from 100 percent natural ingredients and have been scientifically tested—"

I started to chuckle, and she wanted to know why. "Because you're just like your grandmother," I told her. "We started out on Jil Sander and somehow, within a minute or two, we're on your products!"

Aerin smiled sweetly, then, almost uncontrollably, resumed her sales pitch for Estée Lauder's Prescriptives.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now