Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE DECLINE OF THE SOUBRETTE

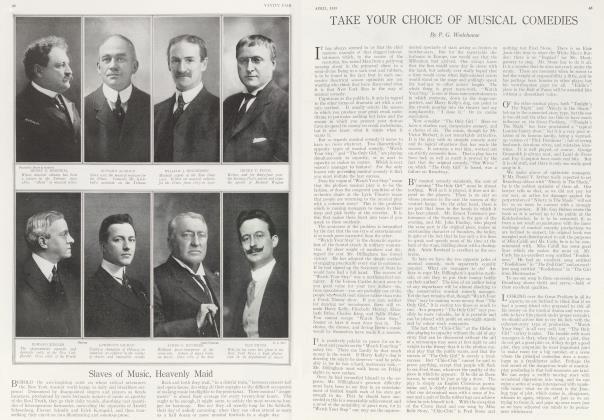

The Sudden Extinction of a Type Once Popular on Our Stage

Leander Richardson

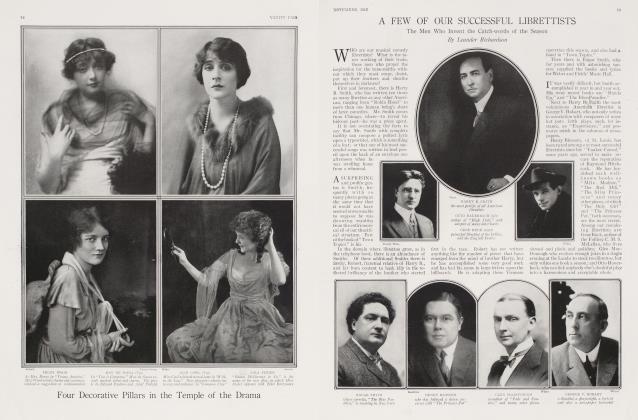

THERE are, alas, no longer, any soubrettes to cheer us on our lonely way. True that we have comediennes, ingenues, and various other purely modern inventions, but these are not satisfying substitutes for the glorious soubrettes of yore. Yet the art of being a successful soubrette was enormously profitable and those who practiced it—to the satisfaction of the great public —retired in dazzling opulence. Hence, one is moved to marvel that soubrettes are no more, and to wonder vaguely if Nature has stopped furnishing the material of which they once were made.

It must have been somewhere in the early Seventies that New York woke up one morning in a kind of dear delirium over the advent of a sunny daughter of merriment carrying the simple name of Lotta. A few there were who later learned that her complete appellation was Charlotte Crabtree, but that fact mattered nothing at all. If she had been known by any other name she would have seemed as sweet.

The first time that own my en raptured vision took her in was at Booth's theatre, at the corner of Sixth Avenue and Twentythird street. The play was "The Old Curiosity Shop," and Lotta doubled as Little Nell and the ragged, hungry slavey. I was somewhere near the advanced and profoundly astute age of twelve, and, right on the spot, I fell desperately, violently, madly, in love.

It was my first attack, and O, how it hung over me by day and went whirling through my dreams at night. Through the intervention of benign providence Lotta never knew anything about it. The gallery of Booth's theatre, during her engagement, was full of other boys of twelve and upward, who were just as much in love with Lotta as I, and so was the balcony, and so was the orchestra beneath. There was quite a love epidemic that year in New York.

THERE probably never was such another furore over a comedy actress in this large city, and it resulted in a long engagement, with more engagements to follow in other cities, and tour upon tour in new plays where the waif sassed the scowling villain and finally proved his utter ruination to the intense and vociferous delight of everybody. So that when Lotta had had enough of the stage, she was regarded as the richest actress in America. She still lives, with a lot of property, including the Park theatre and the Brewster hotel, in Boston.

And, with all her charm and beauty, her quite irresistible magnetism, she never married—which is well, for no mere man was ever remotely worthy of her.

In the early days of the Lotta craze, other soubrettes also came into vogue. There were quite a number of them—all more or less successful—of whom Maggie Mitchell was just about as popular as Lotta herself. These actresses were all sprightly: they could all sing a little, dance considerably, and one or two of them could add to their comedy effectiveness by throwing an occasional note of pathos into their characterizations.

Maggie Mitchell was a vast favorite with the public, and she too retired from the stage with what was regarded at that time as a great fortune. Many of her real estate investments were made in New York, where she lives to this day; the wife of Charles Abbott, himself a well known actor and highly regarded by his associates.

THEN, following in the wake of Lotta and Maggie Mitchell, came "Little Nell, the California Diamond," who had gained her experience and a certain fame in the mining camps of the Pacific coast. As I recall it, she reached New York about the year 1872 or 1873. Like her predecessors, she was youthful, very pretty, and filled with high and bubbling spirits.

Little Nell (her real name, I believe, was Helen Williams) possessed excellent qualities as an actress, and some years after she had ceased to be a soubrette she came back to us as Helen Dauvray, and leased the old Lyceum Theatre on Fourth Avenue, where she played with marked success in serious drama under her own management. As an incident of this cycle in her career she married John M. Ward, then a famous infielder of the New York baseball team. A little later she restored him from matrimony to the more national but less hazardous game— through the elastic and comforting law of divorce.

Helen Dauvray was not alone a clever actress and an agreeable and accomplished woman, but she possessed knowledge of stocks and bonds, and in the securities market she was a successful speculator. She died a few years ago, to the sincere regret of all who had been privileged to know her.

IT was in about the summer of 1875 that a western manager and actor named John E. McDonough came to New York with a dramatization of Bret Harte's noted story "Miiss," and began searching for a soubrette to play the principal part in it. Ada Gilman, a blue eyed, vivacious and exceptionally clever little actress, who had graduated from the famous Boston Museum, was highly recommended, and McDonough sent her a telegram to somewhere in the Maine woods, miles away from the railroad. The dispatch was delayed in transmission, and the manager, who was in a hurry, engaged Annie Pixley in her stead.

Thus, one soubrette, of whom the late Dion Boucicault said she was incomparably the best in any country, escaped a great chance to become a star, and another actress, also conspicuously gifted, sprang almost instantly into fame and fortune.

(Continued on page 88)

(Continued from page 55)

The gradual disappearance of the soubrette type from our stage began to manifest itself in the neighborhood of 1883, when Minnie Palmer was prominent in a tinkly little play called "My Sweetheart."

Reader, believe me, there are no comediennes, or ingenues, or any other modern stage contraptions half as charming as the vanished soubrettes of old.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now