Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNINETY YEARS OF DELMONICO'S

CAPTAIN PRESCOTT VAN TUYL

And Fifty Years of a Famous Head Waiter

OF late, the rumors to the effect that Delmonico's was to move a little further up Fifth Avenue have been persistently circulated—and denied. The facts are that Miss Delmonico decided, only three weeks ago, to keep the famous restaurant where it is—at the corner of Forty-fourth Street—and not to lease a larger building in the Fifties.

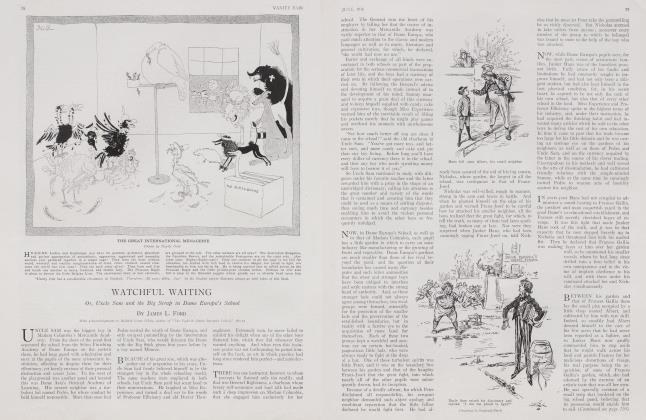

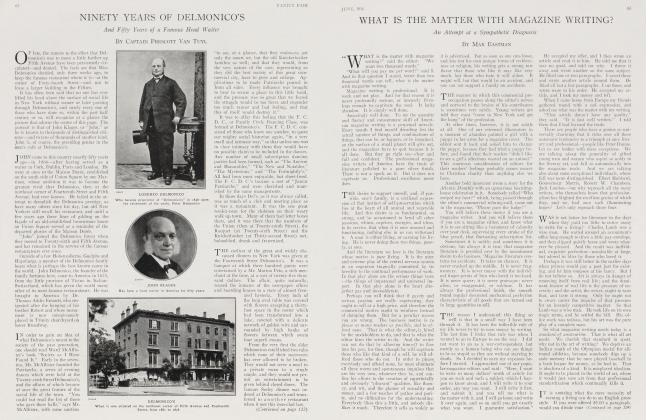

It has often been said that no one has ever lifted his head above the surface of social life in New York without sooner or later passing through Delmonico's, and surely every one of those who have done so, within the past half century or so, will recognize at a glance the picture that adorns the center of this page. The portrait is that of John Klages, or "John," as he is known to thousands of distinguished citizens—and to tens of thousands.of another kind. John is, of course, the presiding genius in the men's cafe at Delmonico's.

JOHN came to this country exactly fifty years ago—in 1866—after having served as a waiter in Cork, Dublin, Paris and London. He went at once to the Maison Doree, established on the south side of Union Square by one Martinez, whose ambition it was to become the greatest rival that Delmonico, then at the northeast corner of Fourteenth Street and Fifth Avenue, had ever known. He failed in the attempt to demolish the Delmonico prestige, as have many others since his day, but old New Yorkers still recall his restaurant, and until a few years ago three lines of gilding on the facade of an old-established brownstone house on Union Square served as a reminder of the departed glories of the Maison Doree.

"John" joined the Delmonico forces when they moved to Twenty-sixth and Fifth Avenue, and has remained in the service of the famous restaurateurs ever since.

Outside of a few Hohenzollerns, Guelphs and Hapsburgs, a member of the Delmonico family bears what is perhaps the best known name in the world. John Delmonico, the founder of the family fortunes here, came to America in 1825, from the little province of Ticino in ItalianSwitzerland, which has given the world many other of its most famous restaurateurs. He was brought to America by Dr. Thomas Addis Emmett, who emigrated after the hanging of his brother Robert and whose monument is now conspicuously placed in Trinity churchyard on lower Broadway.

IN order to gain an idea of what Delmonico's meant to the society of the past generation, one should read Ward McAllister's book "Society as I Have Found It." Early in the seventies, Mr. McAllister founded the Patriarchs, a series of evening dances which were held at the Twenty-sixth Street Delmonico's, and the affairs of which became at once the great feature of the social life of the town. "You could but read the list of those who gave these balls," says Mr. McAllister, with some unction"to see, at a glance, that they embraced not only the smart set, but the old Knickerbocker families as well; and that they would, from the very nature of the case, representing as they did the best society of this great commercial city, have to grow and enlarge. Applications to be made Patriarchs poured in from all sides. Every influence was brought to bear to secure a place in this little band, and the pressure was so great that we feared the struggle would be too fierce and engender too much rancor and bad feeling, and that this of itself would destroy it."

It was to allay this feeling that the F. C. D. C., or Family Circle Dancing Class, was formed at Delmonico's. The F. C. D. C. consisted of those who knew one another, to quote our mighty social historian again, "in a very small and intimate way," so that unless one was in close intimacy with them they would have no possible claim to be included in the dances. Any number of small subscription dancing parties had been formed, such as "The Ancient and Honorables," "The New and Notables," "The Mysterious," and "The Fortnightly's." All had been most enjoyable, but short-lived. The F. C. D. C.'s became a sort of "Junior Patriarchs," and were cherished and nourished by the same managements.

In those days Del's, as it was always called, was as much of a club and meeting place as it was a restaurant. It was the one great rendez-vous for the clubmen on their weary walk up town. Many of them had letter boxes there, and it was there that the members of the Union (then at Twenty-ninth Street), the Racquet (at Twenty-sixth Street) and the Knickerbocker (at Thirty-second Street) met, hobnobbed, drank and fraternized.

THE earliest of the great and widely discussed dinners in New York was given at the Fourteenth Street Delmonico's. It was a banquet at which three hundred guests were entertained by a Mr. Morton Peto, a rich merchant at the time, at a cost of twenty-five thousand dollars. The affair, quite naturally, roused the inmates of the newspaper offices and boarding houses to a state of almost frenzied hysteria. Every inch of the long oval table was covered with flowers excepting a thirtyfoot space in the center which had been transformed into a lake, covered with a delicate network of golden wire and surrounded by high banks of flowers between which swam four superb swans.

From the very first the elder Delmonicos established two rules which none of their successors has ever allowed to be broken. They would not serve a meal in a private room to a single couple, and they would not permit an entertainment to be given behind closed doors. The famous Seeley dinner was ordered at Delmonico's and transferred to another restaurant when it met this iron-clad law.

(Continued on page 122)

(Continued from page 62)

IT is related also that the elder August Belmont once ordered a dinner for four in one of the private diningrooms in Fourteenth Street, and sat there with Mrs. Belmont waiting for their guests who, through a mistake in the date, failed to arrive. Impatient at the delay, the banker ordered the waiter to serve for two, only to be informed that it was against the rule of the house. Mr. Dclmonico was summoned and explained to his irate patron that he had made that rule for the protection of ladies of Mrs. Belmont's caste, and so well did he plead his cause that the pair soon adjourned to the large dining-room. It is further related that Mr. Belmont evened things up by winning bets with several of his friends that Delmonico would refuse to serve them under like circumstances. It was therigid enforcement of this law that gave Solari. also a native of Ticini, his great opportunity. Solari's famous place, on University Place, was the one really dashing, alluring and under-the-rose restaurant of that time.

AMONG John's most treasured possessions are many old Delmonico menus. Some of these are records of dinners given by Samuel Ward, who was the best known gourmet of his time, and who used to go into the kitchen and make his own sauces, while others are the bills of fare of that time. Society feasted more elaborately in the old days than at present, drinking a greater variety of wine and eating innumerable courses, topped off with three or four kinds of pastry and ices. One thing is noticeable in these menus, and that is that until the beginning of the present war champagne at $3.50 a quart was the unchangeable standard of the wine list for a period of fifty years.

Mr. McAllister describes the seventies and eighties as "a golden age of feasting," and it certainly was a much cheaper age than the present, especially in the matter of game, for a quail or half a partridge could be had in season for seventy-five cents. Cold storage birds were then unknown.

IN the days of their greatest prosperity, the Delmonicos were not above doing their own marketing, and every business man of forty years ago was accustomed to meet, as he walked downtown in the morning, Ciro Delmonico, returning in a cab from his early duties in Washington Market. Delmonico's is intimately associated witn many of the old and then leading families of New York—the Howlands, van Burens, Aspinwalls, Hones, Minturns, Stuyvesants, Duers, Jays, Morgans, Livingstones and Cuttings. It was the favorite haunt of such celebrities as Leonard and Lawrence Jerome, Samuel Ward, Peter Marie, William Jay, W. R. Travers, John Hone, James R. Keene, Frank Work. Colonel Lawrence Kip, Colonel Miles O'Brien, Hamilton Fish, Joseph Mora, Tom Ochiltree, Freddy Gebhard, James Gordon Bennett.

THE Weda, a celebrated club which is still in existence, began holding its dinners there as early as 1838. The Weda—"Wyckoff's Economical Dinner Club"—so-called because the first dinner cost $10 a plate, an enormous sum for those days, was started because some of the leading business men of the town could not get home on "packet day," being busy with their foreign correspondence.

General Winfield Scott lived for a long while at Delmonico's, on Fourteenth Street and Fifth Avenue, and his rooms are shown on the third floor of the picture at the foot of page 62. Prince Louis Napoleon, afterward Napoleon III., also stayed there. Charles Dickens patronized the establishment regularly on his second visit to America. Since the first restaurant was opened, it is said that every President of the United States and every statesman of importance has been a guest there at one time or another.

It was the custom of men to "dress" for dinner at Delmonico's from the earliest days in the history of the house, but never on Sundays until about thirty years ago. Women never wore low-cut frocks there— until the nineties. Any woman who showed her shoulders before that time was certain to be a visiting foreigner. Up to the eighties, dinner parties were invariably held at half-past six, while eight o'clock dinners did not come into vogue until the beginning of this century.

John is a splendid example of the old school of waiters. He is the soul of courtesy, dignity, kindliness and tact. He rarely forgets a face, and one of the joys of returning to New York for hundreds of old New Yorkers is to go into Delmonico's and find that John remembers you, that he is glad to see you, and that he forthwith suggests your favorite dishes.

John, the first of the Delmonicos and the one who founded the business, had saved up a little money which he had made as captain of a schooner plying between New York and the West Indies. He quit the sea for good in 1825, settled in New York, and opened a little shop for the sale of French and Spanish wines at the Battery. In 1827 he went home to Switzerland, but soon returned and brought his brother Peter with him. The two went into partnership and started a place at 21 to 23 William Street, where cakes and ices were the specialties dealt in. This venture was so successful that they soon opened another establishment at 70 Broad Street, and sent over for their nephew, Lorenzo, to join them in the rapidly growing business. Lorenzo was followed by three other nephews—François, Ciro and Constant.

DELMONICO'S William Street place was destroyed in the fire of 1835. The brothers then bought the property at the corner of Beaver and South William Streets. The building which they erected on this site in 1837 was described in a newspaper of the time as "upon a scale of splendour, comfort and convenience far surpassing anything of the kind in this country." This edifice is still standing and is still operated by the Delmonicos.

John died suddenly, while out shooting on Long Island in 1842, and the aged Peter took his nephew, Lorenzo, into full partnership. The Broad Street house was burned in 1845, and, the following year, the Delmonico Hotel was opened at 27 Broadway. This hotel later was purchased by an old sea-faring man named Captain Stevens, and is. still standing and still doing business as The Stevens House.

PETER retired in 1848, leaving Lorenzo as sole proprietor of the restaurant. The latter, whose portrait is shown on page 62, then associated his cousin Ciro with him in the business. In 1855 the Broadway and Morris Street house was abandoned and a new restaurant opened at Broadway and Chambers Street, while, in 1861, the Delmonico place at the northeast corner of Fifth Avenue and Fourteenth Street was opened.

President Lincoln was the most distinguished of the guests of this place In 1876 the Chambers Street restaurant and the Fourteenth Street house were abandoned, the former being moved to Broadway, one door north of Pine, while the Fourteenth Street establishment was taken to the new building at Fifth Avenue and Twentysixth Street, which later became Martin's, and which, two years ago, was razed to the ground. For a short time there was also a Delmonico restaurant at Broadway and Worth Street.

distinguished (Continued on page 124)

(Continued from page 122)

LORENZO died in 1881, and the death of Ciro the same year brought to an end the batch of nephews—Lorenzo, Ciro, Francois and Constant—who had inherited from the original John and Peter. Lorenzo and Ciro were succeeded in turn by their nephew, Charles Crist Delmonico, who in turn, on his death in 1884, was succeeded by another nephew, Charles Crist, who later took the name of Delmonico. When he died, "Aunt Rosa," as she was always called, became head of the house, and her only surviving nephew, Lorenzo, brother of the last Charles Crist Delmonico, became associated with her in the business. At their death the business passed into the hands of Miss Josephine Delmonico and the widow of Charles Crist Delmonico, who between them are responsible for its present management.

A WEALTH of legendary— some founded on truth and some quite mythical—clusters about the Twenty-sixth Street Delmonico's, and some of it relates to a "blacklist" which contained the names of men who were not to be served there. Anyone rash enough to start a fight was entered on this "blacklist," and although the management did not run counter to the law by definitely refusing to supply him with food and drink, he simply could not be served. A waiter would take his order with grave politeness, hurry away and not return. The head waiter, when appealed to, would follow the same course, and finally the "blacklisted" one would slink away and never come back. It is said that a young man on the "blacklist" received an invitation to a large dinner in a private room, and boldly took his place among the guests. Everyone except himself was served while, despite the remonstrances of his host, he was compelled to go hungry.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now