Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowVAGARIES IN MOTORBOATS

GEORGE W. SUTTON, JR.

Picturesque, Practical, and Peculiar Put-puts

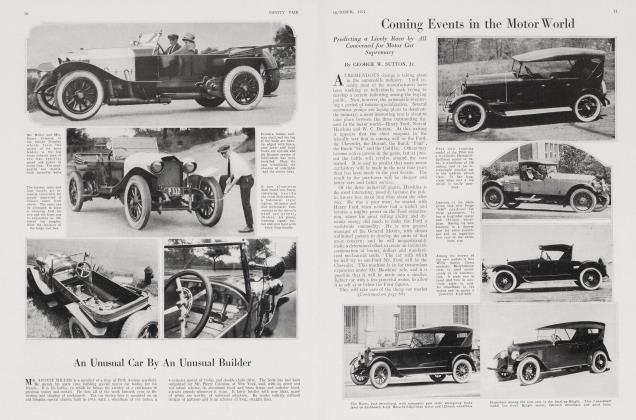

A FREAK is one thing. A novelty is quite a different matter. A freak is out of the picture. It jars on the optic nerves because it is incongruous with our normal notions of the proper appearance of things. A novelty is often the product of so artistic an imagination that it actually enhances the art of Nature. Motorboats fall into three classes—regular, freaks and novelties. With freak motorboats we have no patience, because their only accomplishment is to satisfy the vanity of their owners and to blur the landscape in some of our prettiest harbors. The boats pictured here were built on a solid foundation of wisdom either to overcome some mechanical or natural obstacle or to give expression to some artistic idea.

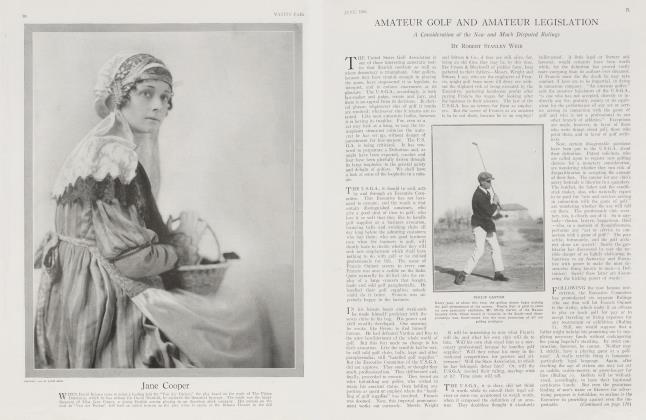

should be grateful to the owner of Halcyon. He had an idea. He wished to preserve the grace and beauty of bygone days in combination with the comforts of our modern life. He commissioned Mr. A. Loring Swasey, naval architect, of Boston, to put his mind-picture into definite form. The result was a craft fashioned on the lines of a Columbus caravel. Her presence in any harbor makes a picturesque enrichment of the landscape. While in design she goes back several centuries, she is nevertheless a tremendous step forward in motor houseboat building. To realize this, compare her appearance with that of the squatty, square houseboats you have seen. Her fittings include most of the luxuries of the Biltmore minus the skating-rink.

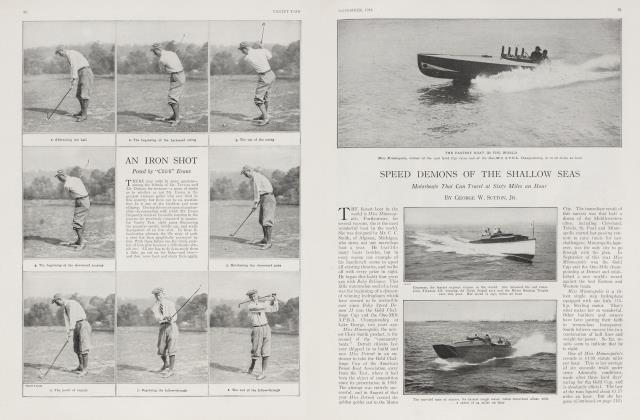

ANOTHER motorboat produced by a careful study of perplexing difficulties is Yolanda II. She looks like the result of a three-cornered spring offensive between a touring car, a pontoon bridge and a pair of Don Quixote's windmills. At first glance you will be positive her owner is a certain fall fruit much admired by rodents. But you will be wrong. Yolanda II solved the problem which had bothered a whole government. Down in Colombia there is a river, the Magdalena, running six hundred miles between Bogota, the capital, and the Port of Barrancuilla. Gonzalo Mezia has the contract to carry mail between the two points, up the river which has an average depth of two and one-half feet and is full of driftwood and weeds. For four years he has wondered how to improve on the running time of the shallow-draft river steamers. They took twelve days to make the trip. D. Lachapelle, of Nyack, N.Y., did it by designing Yolanda II. Her draft when running is three inches. Her speed with two air propellers is over thirty miles an hour and she beats the record of the steamers by eleven days. Her time for the trip is somewhere around twenty hours. Another shallow water boat has been devised by a Canadian sportsman who used to pole seven miles up a sluggish stream until he conceived a boat with air propellers and an air rudder. ,

SOME day some one is going to find a real use for amphibious motorboats. Then the ones which have blossomed and have been discarded every year for a long time will be taken out of camphor and put to work. An amphibious motorboat is either a boat which will run on land or an automobile which will run in water, whichever you prefer. Its technical name is hydro-car. Several have been built which have performed fairly well under ideal conditions but most of them have been found lacking in class as automobiles and deficient in seaworthiness as boats. Yet there is a decidedly sane idea back of them which may some day be worked out satisfactorily.

THE yearning for unlimited speed has accounted for a great number of unusual boats. Last year's most famous example was Tiddledy Wink with her bizarre looking wings. Every year sees the appearance of some peculiar looking racing boat whose builder thinks he has solved the problem of excessive speed. Most naval architects work on the theory that speed germinates in a clever combination of hull lines, weight and power. But there is something in the idea that some unusual "kink" may solve the problem. Cooper Hewitt invented a boat with a series of underwater fins which were to raise it up until it went bouncing skittishly over the waters, barely touching the surface. This was about the beginning of the hydroplane; and, today, practically all racing motorboats which can attain a speed of over forty-five miles an hour are hydroplanes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now