Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE NEW GAME OF PIRATE BRIDGE

The Third Article on the Game Which Seems Destined to Supplant Auction Bridge

R. F. FOSTER

BEFORE proceeding to discuss the principles of bidding and accepting at pirate, attention should be called to an error into which auction players may be tempted to fall. This is putting dummy between the two opponents in every hand, instead of laying it down where it belongs. Some imagine this is the better way, because they are accustomed to it, but it is a distinct loss. One of the prettiest points in pirate is bidding on the probable position of the partner's hand.

In auction, a band has only one value, and that is the tricks it contains. In pirate every hand has three values, according to its position with regard to the partner. This adds immensely to the interest and variety of the game, as many a hand that did not seem to be worth more than one or two tricks may suddenly become worth four or five. In order to make this point clear, let us take an example

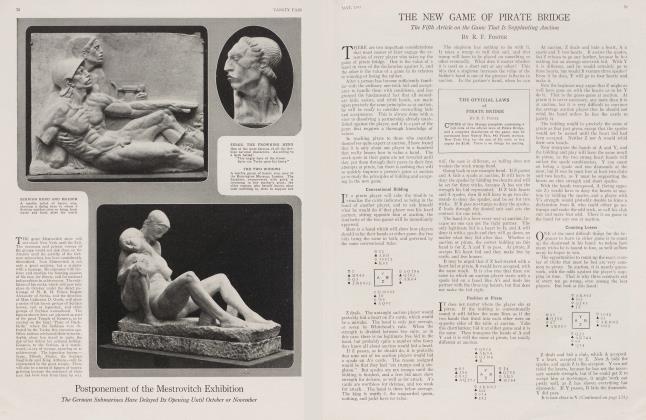

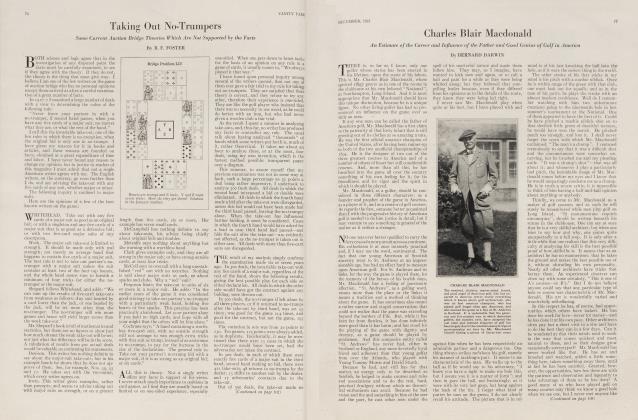

The bidding on this hand leads up to an interesting situation. Z deals and bids a club, which A accepts. Y passes, but accepts B's diamond bid. Z bids a spade, which B accepts. A, two hearts, which B accepts. Z, two notrumps, which A passes.

Y cannot accept this bid, because of his position with regard to his prospective partner. His diamonds would be led through and killed. He cannot protect the spades, which B has shown strength in, and has only one trick in hearts, which suit B has also accepted. When Y passes, B accepts the two-no-trump bid, Z and A passing.

Now Y sees the chance to enhance the value of his hand by a shift in the position of his partner, and bids three no-trumps over B's acceptance, aiming to get B for a partner. In this he succeeds, and goes game. Z opens his partner's (A's) acceptance in clubs and wins the return with the ten. If he tries to drop the clubs, he establishes the queen, and five diamonds, two hearts and a spade win game for Y. If he shifts to the hearts, five diamonds force the decisive discard and then a small spade lead from B (the dummy) makes the spade jack or the queen of clubs.

At auction, Y's hand is worth only one thing, and that is nothing, with a fixed partner. At clubs or no-trumps he will be set. With hearts played against him he loses two odd, with notrumps against him he loses the game. [At auction, Z bidding clubs, B would double and A would go no-trump.]

At pirate, Y's hand has three values. With Z for his partner, it is worth nothing. With A, the odd in hearts. With B, a game in no-trumps.

Free and Forced Bids

A FREE bid is one that the player is not obliged to make at the time, such as the dealer's opening declaration. There is absolutely no excuse for any free bid that is not conventionally sound. A forced bid is one that must be made in order to overcall a previous bid and acceptance. An attack has been established, and it is imperative to show anything that promises a defence or counter-attack.

Players must be careful to distinguish between these two classes of bids, both in making and accepting them. A forced bid must not be credited with the same conventional strength that is required from a free bid. Bids made on the second round by a player who passed an opportunity for a free bid on the first must be regarded as forced bids.

Absolute Bidding Values

WILBUR C. WHITEHEAD'S rule for measuring up a hand is probably the best for the purpose, as it applies equally to suit bids and no-trumpers. This calls aces sure tricks; kings probable, and queens possible. Two kings are considered as good as an ace, and two queens as good as a king, if well protected. Unattached jacks and tens have no absolute values.

This allows us to attach numerical values to the high cards, so as to present their relative values in graphic form. Call an ace 4, a king 2, and a queen 1. As there are 7 such values in each suit, the pack is worth 28, and the average value of any hand must be 7. If the hand is above average, 8 or more, it is always worth a free bid, provided the kings and queens are well guarded. A singleton king or queen is regarded as worthless.

In addition to these separate values, a king with its ace must be worth as much as the ace, and a queen with its king must be worth as much as the king, as either card might be played to a trick with the same effective result. Therefore an ace-king suit is worth 8, and a king-queen suit is worth 4. While jacks and tens have no separate values, in combination they may have. A jack with a queen, for instance, is worth as much as the queen, and jackten of a suit is equal to a queen if well guarded. These values may be combined with higher honors. The king-jack-ten, must be as good as the king-queen, and worth 4. Ace-jack-ten must be worth 5, the same as ace-queen.

Major and Minor Suits

HE major suits are hearts and spades, and always desirable as trumps. They are bid with the understanding that the acceptor hopes they will be the final declaration; therefore the bidder must have both the strength and the length for a trump suit. The minimum strength

THE OFFICIAL LAWS of PIRATE BRIDGE

BY R. F. FOSTER

(COPIES of this 36-page pamphlet containing a full code of the official laws of Pirate Bridge, and a complete description of the method of play, bidding, acceptance, scoring and settling, may be purchased from Vanity Fair, 443 Fourth Avenue, New York City, for the sum of 25c each, or five copies for $1.00. No charge for mailing. for a major-suit free bid is five cards, and a hand that will count to 8 or more, at least 4 of which should be in the suit itself.

It takes five by cards to win the game with a minor suit, clubs or diamonds, for the trump, and these suits are therefore better fitted to support a major suit, or to fill out a no-trumper. There are many hands, of course, in which a minor suit will go game, but no good player ever starts with the idea of working to get five odd, when three or four might be enough, unless, indeed, he happens to hold a phenomenal hand.

Free bids in minor suits require the same absolute values as the major suits, but length is not so important if the suit is not to be the trump. At auction, good players insist on the length, because of the danger of being left with the contract, or the partner's assisting the bid, from which there is no escape. This danger does not exist at pirate, and one may bid short minor suits with greater freedom, provided the hand has the required values.

Take the dealer's hand in the example already given. His club suit counts 5, and the spades 4, a total of 9; but it is not a spade bid, because the suit is not long enough. The beginner should realize the great importance of studying these values in every hand he picks up, always remembering that there must be enough small cards with the minor honors to protect them. Three to a king, or four to a queen may be counted upon with confidence.

Two-Two-Trick Bids

HE auction player will have to revise his theory of two-trick bids when he comes to pirate. At auction there is no longer any such thing as a free bid of two in a minor suit, except when you have nothing in it. Two tricks in a major suit show five cards to four honors, or a seven-card suit. Three tricks is always a shut-out.

At auction, two-trick bids in a major suit will probably be final, as the partner is obliged to stand for them, whether he likes it or not. At pirate, nothing is final until the bid is accepted.

When a player bids one trick in anything at pirate he expects that any player who has a sure, probable, or even possible trick in the suit will accept him, simply to open up.the bidding and show the distribution of the suit. If a free bid is made with ace king and others, the player with three to the queen, or four to the jack ten, will accept. The one-trick bid is a confession that the bidder wants some assistance in that suit.

But suppose he holds five to the ace-kingqueen? No one has the queen to accept with, and it is improbable that any player will hold four to the jack and ten, so the bid will be passed up, and it will look as if some one was holding off when he should have accepted. This at once throws a doubt upon the possibilities of that suit.

For this reason, when a player holds a solid suit, such as six or more to the ace-king-queen, or five to any four honors, he should start with a free bid of two. This shows that he can attend to the entire trump situation himself, if that suit proves to be the trump. All he wants from his acceptor is outside tricks.

There are many hands, of course, in which the distribution is such that a one-trick bid cannot be accepted, because the outside honors are unguarded. A club bid on five the acc-king-ten, for instance, may find the queen alone, or with only one guard. This leads players who have the last say to accept with only four small cards of the suit Any player should accept with five. If two pass a one-trick bid, the minor honors must be short-suited, if the third player has nothing as good as the jack.

(Continued on page 114)

(Continued from page 73)

When a player with a solid suit overcalls a previous bid and acceptance, he should overbid his hand. That is, he should call two diamonds over an accepted club if his diamond suit is so solid that no one could accept it. These two-trick bids sometimes lead to some very interesting situations in scheming to get the right partner. Take this case, and note how Y and B get together

Z dealt and bid a spade, which A accepted. Y bid three diamonds, B accepting, as he could ruff the spades. Z dropped the spade suit and overcalled B's acceptance with four diamonds, which Y accepted. Now B wants to show Y what he accepted on, as Y knows Z accepted on the spades. Y can then take his pick. B bids four hearts.

A dare not accept, as he had too many losing cards. Y at once saw that if B had the hearts he was a better partner than Z, and must be short in spades, as that suit lay between Z and A, so Y accepted four hearts, to keep the bidding open, whereupon B went back to five diamonds, accepted by Y, and made it. Had Y passed the four hearts, the bidding would have been closed, as Y is an acceptor and cannot bid, and B's bid would have been void.

Y and Z could not have made more than four odd, but by ruffing the second spade and discarding Y's third spade on the ace of hearts, B wins the game by leading through Z up to the queen of clubs in Y's hand.

Three-Trick Bids

A THREE-TRICK bid is exclusively a shut-out bid at auction, as there is no necessity to bid more than two on any suit unless one is afraid of some other suit that it will be too expensive to overcall.

There are no shut-out bids at pirate, and a bid of three simply adds a little information to the bid of two. Two shows a solid suit; three shows an outside ace as well. At auction such a hand would be a sporty no-trumper.

There is no necessity to take these sporting chances at pirate, because any player who holds five or six solid tricks in one suit and the ace of another will inevitably be the declarer or acceptor on the final bid, whatever it is. The thing to do is to bid the solid suit and let the others figure out which ace goes with it.

These bids of three are not common, but they are rather exciting when two different players are fighting for the prize. The second illustrative hand published in the January number of Vanity Fair was an example of a free bid of three tricks. Here is another, in which the situation is taken advantage of in a different way:

Z dealt and bid three hearts. With only one sure trick in his hand, A passed. Y passed because he wanted to bid the spades and score 72 in honors.

B accepted. Y then bid three spades, which B accepted. Z bid four hearts. When a player rebids his hand in this way, it shows that there is more in it than disclosed by the original bid, but where the extra strength lies in this case is not apparent to any player but A, who sees that Z might have the king and queen of clubs, as well as the ace of diamonds, or he might have both ace and king of diamonds. The ace of diamonds is marked in Z's hand by the spade bid. A accepts.

B accepted Y's four-spade bid, but refused to accept five, when Z bid five hearts, accepted by A, as B saw his king of hearts trick was lost if A led through it. This shows good judgment on B's part, as he would have been set for two tricks on a five-spade bid before getting into the lead. Z would open the singleton club, ruff the return of the club by A, and lay down the ace of diamonds and ace of hearts.

The reader should observe that being set on a contract is a losing game at pirate, as the game is seldom worth more than a hundred points, unless it is a slam.

There is a small slam in die hand for A and Z, no matter what Y leads. The actual play was instructive in showing how tenace suits are managed, by placing the lead, when partners are next each other with the high cards on the right. Y led the spade, and seeing dummy had no more, shifted to the diamond. Z won this trick with the jack.

The play now is to catch the king of diamonds, and also the king of trumps. Z ruffs dummy with a spade, and leads the smallest trump. Two rounds of trumps finishes that part of the play, and Z puts dummy in with the ace of clubs to come through with a diamond. As this fails to drop the king, dummy is put in again with the smallest trump and leads diamonds once more.

Bidding No-Trumpers

THE no-trumper is the special delight of the auction player, but if his feelings are carefully analyzed, it must be acknowledged that the enjoyment is in the play of the cards and not in the bid itself. The declaration is always more or less of a gamble at auction. So well is this known that it is an axiom among good players that, "anything can happen to a no-trumper." There is a club in this city that has that motto framed on the wall.

One school believes in taking out no-trumpers every time the partner holds any five cards of a major suit. Another teaches never to rescue except on strength, and with a weak hand to abandon the notrumper to its fate. Some teachers draw the line between a queen and a jack in taking out with a minor suit, and so it goes.

(Continued on page 116)

(Continued from page 114)

All this controversy is cut out of pirate. Here is a rather remarkable illustration of the difference between the two games when it comes to bidding notrumps. The hand was originally played at the Knickerbocker Whist Club, long before pirate was invented, but it is an excellent example of the truth of the adage, "anything can happen to a no-trumper'' (at auction) :

Z dealt and bid no-trump. Every one passed. Y has no five-card suit, no warning bid, no rescue, no take-out. B cannot ask for a heart lead, as he has no sure re-entry. A led his fourth-best club, and B returned it, discarding two diamonds and two spades, without a reverse discard in either, so A laid down his ace of hearts, getting the encouraging eight from B. He laid down the ace of diamonds and then led another heart. A grand slam against a no-trumper, 605 points, if a game is worth 125.

In pirate, no one bids no-trumps on a hand like this. Z would start with adiamond, so as to locate the ace of that suit. A would accept. B would bid the hearts and A would accept. Now Z goes to notrumps and it is up to A and B to settle between them which gets him, as he can go game with either. If A is the partner, Y will lead B's hearts, and Z makes one heart, four diamonds and four spades, by leading spades at once, through the jack. With B as the partner, Z makes two clubs if A leads clubs, which he surely will, three spades and four hearts; or one heart. If A holds up the ace, three spades and three diamonds. The reader will see that B will abandon the hearts if the ace is held up, as he has no re-entry.

Feeling Out No-Trumpers

IN pirate, no-trumpers are invariably postponed bids, unless the player holds 100 aces, and these postponed bids are based on inferences from the bids or acceptances. The careful player feels his way.

It may be laid down as an axiom in the bidding that a free bid of one no-trump is a waste of time and opportunity at pirate. Every one will pass it up and then some one will declare a long major suit and compel the no-trumper to be the acceptor instead of the declarer.

THERE are two ways, to lead up to a no-trumper. depending on how much it is shy. One method is to bid the only missing suit, if that is the character of the hand, and then go at once to no-trumps. This shows that the only help wanted was in that suit

This distinguishes the bidding from that followed in the second method, in which it is necessary to bid two suits, or hear from them. If these are located in the same hand, the rest is easy. If they are not, some judgment must be used in determining whether to bid no-trumps or not A suit may be more promising at that stage. Here is an example of the first method, which might be called the one-try no-trumper:

An auction player would bid no-trump on this hand of Z's and that would end it. All he could make would be two odd, as A would open the diamonds. At pirate, if Z starts with a bid of one no-trump, no one will accept him. No one has a hand that counts anywhere near eight by the Whitehead system. When that bid is void, no one has a legitimate bid in anything, and the hand is thrown out.

But at pirate, Z starts with a diamond bid, just to feel out the location of the tops in that suit. Y accepts, but B overcalls him with two diamonds. A might accept this, but whether it is accepted or not, Z has another bid and goes at once to no-trumps. Y cannot accept, as his diamonds will be led through. B accepts, and Z goes game by leading twice through Y's hand.

Here is an example of the other method, in which the no-trump hand makes two tries before he is sure of his ground:

Z dealt and bid a diamond, accepted by B. Then Z bid a club, accepted by A. As neither Y nor B make any mention of the spades, although both have had a chance, Z correctly assumes that the spade suit is split up, and he bids no-trump, accepted by A. This is what Z wants, as the reader will observe that although B has the diamonds, they can be led through. If the diamonds were with A and the club with B, the notrumper might not work so well. B could have conveyed the same information by doubling A's acceptance.

It does not matter what Y leads, provided Z manages the diamond suit correctly, leading it from A's hand the moment he gets the chance. In the actual play, Y led the ten of hearts, and the queen won. A small club put A in to lead the diamond, and B passed up his partner's ten.

If Y had opened with the spade, the play would have been closer. The ace wins, and the diamond lead follows. If B puts up the ace and returns the spade, three spade tricks do not save the game. If B leads a heart, instead of a spade, Z goes right up with the ace and makes two diamond tricks later, instead of two hearts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now