Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE NONSENSE ABOUT "ART PATRONS"

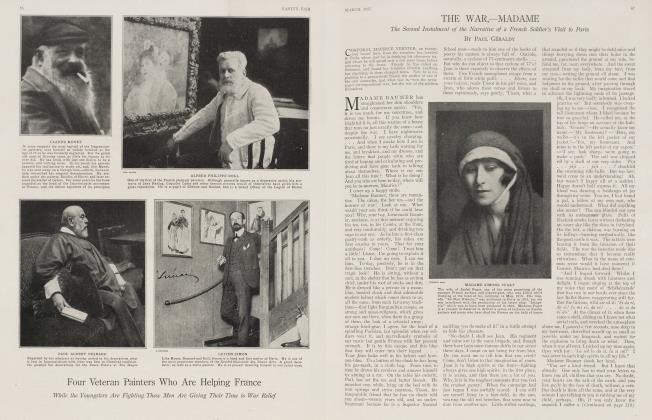

ARD CHOILLE

The Difference Between a Patron of Art and a Collector of High Priced Paintings

THE collector of old masterpieces is in no true sense of the word a patron of art, though he may be, what is quite different, a patron of museums. The real and the great art patrons of the world have always been interested in the work being done around them, and the men doing it. On one occasion a Pope threatened to take his army and bring back a painter who had run away from Rome, and a job, to a city of northern Italy. In this age the only good artist is a dead artist, because it is only when the breath is out that the dealer ann the buyer can be quite sure that the painter or the sculptor will do nothing to interfere with his established and valuable reputation.

ONE of the few exceptions to the general rule in New York is Mrs. Harry Payne Whitney. She has not been a collector of old masters in the ordinary sense. Herself an artist, she has always been more interested in production than in acquisition, in what is being done, or in what may be done, than in what has been done. She has ordered and planned and bought and aided in every way in her power, so that young artists,—painters, sculptors, decorators, etc.— might be helped along in this country. Even if it could be shown that now and then she made an error in judgment, it would still be true that it was done in the right spirit. Some artist got his chance even if he failed to live up to her— and our—expectations. Perhaps in time there will be many, many other Americans, who will believe that the artist ought to be left free from the influence of the shop and the exhibition gallery; that he should have a definite order to fulfil, that he should have time to think, and that he should be allowed to think in his own way. That is, in my judgment, being a true patron of art.

IT is said very often that the status of artists in America has improved. Socially perhaps, but otherwise hardly. Do our artists get anything like the opportunities to put their brains into their commissions in the way that used to be common before the collectors took the place of the people— in Salem, Boston, Virginia, Philadelphia— who had things made that they wanted to use, and live with, and not merely to gather for arrogant display? Instead of desiring to bring about the production of what would be characteristic of the period he exists in, the so-called art-patron of our day is only really serious when he is in hot pursuit of what was characteristic of a period long past and done with—provided it has a sure market value and can be turned into cash without any great difficulty:

There is a form of art patronage which we should all strive for, which too might have great results in the development of American art. If some of those who have the privilege of spending large incomes were to back American artists, particularly young American artists, not merely to paint pictures and decorations, and to make sculptures for them, but to do more—to design rugs and tapestries, silverware and jewelry and glass, fireplaces and halldoors, an end might be put to the pervading and stultifying fashion of imitation and vain repetition, and those who come after us,—in fifty years' time—might be led to believe that this age had really done something to advance the arts in our country. The hardest part of it all would be to leave the artists alone—unhampered by silly, or ignorant, directions. That would be essential.

If this fine method were resorted to—of employing living artists to design everything we needed—mistakes would of course be made, but there would always be the chance of getting somewhere in the development of a characteristic and vitalized American art. The stunting limitations of tradition, induced by fear of all originality, would be far less powerful than at present. But now a word or two as to the real art patron!

Until the majority of our collectors are reformed, and brought—like Lorenzo de Medici, Louis XIV, the Italian Popes, Pericles, Mrs. Whitney—into the other state of mind, New York will be an art centre only in the sense in which the expression is understood by picture dealers and auctioneers. And now for a word or two about our great collectors, who are so often wrongly named "art patrons," the Morgans, Wideners, Fricks, Altmans, Kahns, Walters, Evanses, etc., etc.

As Europe sinks deeper and deeper in debt, while this fortunate part of the world takes on more and more the aspect of a great creditor community, the question, "What will they do with it ?" becomes more and more pressing and interesting. Of course, for one thing, they,—that is to say, the rich—will acquire a few more homely comforts; new town houses and country houses, bigger yachts and a larger school of motor cars.

BUT, it may be pointed out that, quite early in our social history, the discovery was made that the easiest way to climb was in the disguise of an art patron. Not only did the collector as such get a reputation for taste, discrimination and cultivation, but, if he had fairly good advice from the sensible, and usually Semitic, dealers, he was quite safe against financial loss. Stocks and bonds might make him respected in the Wall Street neighborhood, but these were too commonplace to raise him in the estimation of his fellow men uptown, while paintings and Chinese porcelains not only served a social purpose by glorifying the family, but were actually to be classed among gilt-edged securities.

The public take off their hats in a picture gallery, even if it is only in the back room of a shop. That is because there is supposed to be something sacred in a work of art. So, to own great works of art is to have a claim on the consideration of those who cannot have any ambitions in that direction. Yet the person who collects pictures with the conviction that their prices will go up, and has the determination to sell at the right moment, can hardly be distinguished from the shrewd speculator in railway bonds, or in unimproved real estate in the Bronx.

Every new great house, now set up on upper Fifth Avenue, seems to have its art gallery, sometimes a little more imposing on the outside than on the inside. These spacious chambers yawn for the treasures of the world. But they and their contents do not represent any real patronage of art, but merely the purchasing of a commodity which can be sold at an advance whenever the need for ready money becomes at all urgent. These sure things, with established reputations, are tucked away in the palace. They represent the assets of the owners as surely as do the contents of their strong boxes in safety deposit vaults. The ultimate test of the auction-room causes no uneasiness, for it is easy to discount that in advance, if the test has not been applied already.

(Continued on page 136)

(Continued from page 37)

WITH death duties mounting, and the income tax steadily increasing, the great families abroad will soon be forced to part with works long associated with particular places. Not even the portraits of their ancestors are safe from the drawing power of New York as an art magnet. A good Raeburn will soon be as scarce in Scotland as a first rate Manet in England, or a collection of fine Georgian plate in Ireland. Not since the Oxford colleges melted their silver to supply the needs of King Charles in the Great Rebellion has there been anything like the present denudation of works of art in the British Isles.

There is no doubt that New York has become, for the time being at least, what we love to call the art centre of the world. Buyers and sellers flock here, whether the articles coming under the hammer happen to be the furnishings of the former royal palace in the Forbidden City at Peking, or the latest collection of Monets to come on the market. New and recordbreaking prices have been obtained, and Mr. Kirby, of the American Art Association, has ceased to be surprised at anything. It is a fine time to die, if you have a good selection of objéts d'art to swell your residuary estate, and some nice relatives to leave it to.

Yet, after all, most of the art fuss and commotion is of the purely barren sort. When the lights are turned out in the ballroom of the Plaza, and the "greatest sale of the season" is over, what has happened ? A, B and C now own the old masters that once belonged to D, E and F. It is like taking something out of one pocket and putting it in another. Nothing has been added to art but a new cash value.

A popular and prosperous young Irish tenor in New York buys a celebrated Rembrandt, reproduced in all the books, with a history that has never had a doubt cast on it by Dr. Bode or Mr. Bernhard Berenson, and people wonder, not that the tuneful one should take to picture-buying, but that he should have caught so soon the manner of the city of his new adoption. For a Rembrandt may be turned as readily and rapidly into money, at any moment, as a string of matched pearls, or a diamond, or a ruby. Give a credit expert a list of a man's possession, in the shape of old masters, and he will tell you their cash value as easily as if the list were one of railway shares.

THE circulation of admitted masterpieces, from one owner to another, means nothing as far as the welfare of American art, or the general welfare of the public, is concerned, except that one proprietor may be more inclined than another to let properly introduced strangers into his palace to see what hangs on his walls.

So the Garland Collection becomes the Morgan Collection—or part of the Morgan Collection,—and a part of the Morgan Collection becomes a part of the Frick Collection, or the Widener Collection, or the Johnson Collection, or the Kahn Collection. As far as furthering artistic progress is concerned, the whole process amounts to nothing at all. No artist has been helped one iota by any of these great speculator collections. They have done nothing to develop new artists, new artcrafts, new sculpture, engraving, etching, or designing.

Some of the very early American collectors were more willing than their present speculative successors are to take a chance. The French Impressionists found buyers here—Mr. Shaw, of Boston, and others— long before the Beaux Arts students and the infallible George Moore had stopped laughing at them in Paris. That showed discrimination, or conviction, or, at any rate, a fondness for a sporting risk—in short, a true patronage of art.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now