Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA NEW KIND OF ART EXHIBITION

Anybody Who Has Ever Painted a Picture, or Made a Sculpture, Can Show It—Without a Jury

FREDERICK JAMES GREGG

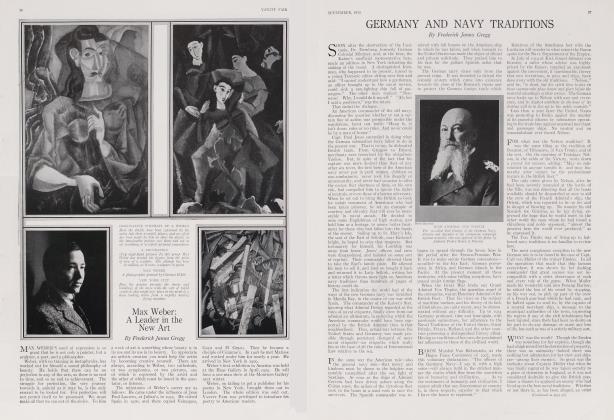

THE first annual exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists,—at the Grand Central Palace, New York,—which is to continue until May 6, has the high virtue of novelty, something the town loves dearly. The two thousand works make up something different in kind from any show of which we had previous knowledge. The Committee, to which William J. Glackens gives high prestige as President, and of which John R. Covert is Secretary, acted simply in an executive, and so not at all in a judicial capacity.

It got into touch with artists all over the country. Anyone, man or woman, famous or obscure—the always rejected or the always accepted—who had painted a large picture, or two small ones, or made a large sculpture, or two small ones, got the right to show, simply by joining, and without the intervention of any person or persons, to decide as to fitness or unfitness, desirability or undesirability.

BY adopting the motto "No jury: no prizes," the Society struck a blow at two vicious and corrupting influences in the art life of the country, and indeed of art life everywhere—the jury and the medal. It came out flatfooted against politics, favoritism, influence, backstair intrigue, and the fine old working principle of you-scratch-me-and-I'll-scratchyou, all of which are part of the jury and prize system. But it did more. In deciding to have no hanging committee, and to hang the paintings in alphabetical order, according to the namgs of the members, as far as physically possible, it went further than the famous Paris Independents, with their hanging committee, and knocked down the last barrier separating the work of the artist from the general public.

Here are good pictures beside bad; clever pictures beside stupid pictures, brilliant pictures beside quiet pictures, Academicians beside Modernists, but nobody can complain, except against some ancestor whose choice of a family designation may have landed a work of art, or pseudo-work of art, on an undesirable bit of wall. To have adopted the group system would have involved a return, or a partial return, to the jury system. It might have resulted in a more harmonious exhibition, as a whole, but it would have meant an abandonment of the rule of equal treatment for all. As it is, the visitor must do his own picking and choosing, without any assistance from the Society, as to what is bad, good, better or best.

CONSIDER an ordinary jury at work! Here are so many old and young men, engaged on the task of making a selection from the paintings and sculpture submitted, half of which only can be accepted. To begin with, some works go in without choice, because of the rank of the artists who sent them. Then come the contributions of those who have strong official friends. These are usually equally fortunate. The jury gets tired. Brilliant things are rejected almost unnoticed, unless some one, with quicker or more honest eyes than the rest, insists that they be brought back for a second scrutiny. There is usually on a jury some energetic conservative who, not satisfied with voting "no" on anything that shows originality of any sort, carries his persistence so far as to call for a review of good works which have been accepted already. Even if such a one fails in his purpose, he is ordinarily skilful enough in turning defeat to his own purpose, by means of compromise. He withdraws his opposition, perhaps, in consideration of the jury's accepting some stupid production by a friend, or a former pupil. As most of the wire-pulling is done, not in the interest of art, but quite contrary to the interests of art, it is easy to see why the jury system, rejected by the Independents, has produced such deplorable results in the past.

If—to take a case—the lady from the provinces, who didn't think she painted, but would rather like to try, is represented at the big exhibition, together with other amateurs, it simply means that, for the first time in history, those who would have been judges have refused to judge. It is "up to" the public. Then the interesting question arises: As the artists responsible for the show have refused to express an opinion about anything displayed, will certain of the professional critics have the grace to keep their hands off; or, on the other hand, will they constitute themselves a jury—after the fact—by proceeding to pick out what they regard as of importance, and what not? Will they take the exhibition as a whole, as a significant and important whole, or will they proceed to award virtual prizes, of more real value than medals, in the shape of long notices, or nice notices, to those with whom they are on terms of friendship, or will they condemn with their pity, or not mention at all, those whose studios they are not in the habit of visiting? In a word, will the true spirit of the Independents prevail, or not ?

The Independent Exhibition is not the descendant of any other exhibition. It is its own ancestor. It has quite different aims and objects from the Armory Exhibition of 1913. That show, got together through the energy, and under the sole direction of Arthur B. Davies, had but one purpose, to indicate the art development of a century. In one way it helped the Independent enterprise, by preparing New York for any new experience. For now we are not surprised at anything.

It is to be regretted that President Glackens' society should have hit upon a time for the show when the minds of men were occupied with the future of this nation. But it stands for the spirit of the greater freedom that all real Americans confidently believe will mark the end of the War. Art, like a man, can live truly only when it is free.

AND, while we are discussing new tendencies in the exhibition of works of art, it might be well to draw attention to the fact that the exhibition of the sculptures of Charles Cary Rumsey, at 142 East 40th Street, New York, which opened on April 9, and is to continue until May 5, is to have'an interesting development, for him and for the general public. Mr. Rumsey is to be evicted from his studio, for the benefit of other sculptors. The explanation of this piece of ruthlessness is as follows: While the place was being prepared for the show, Mrs. Rumsey had an idea, which she communicated straightway to some of her friends, who quite approved of it, possibly to the dismay of Mr. Rumsey. It was this; to turn the ground floor into a permanent institution, to be called the Sculptors' Gallery, in which exhibitions should be held, from time to time, throughout the season, whenever there were important things to put on view, special attention being paid to works in the case of which there was any difficulty of finding hospitality elsewhere. The two large rooms are admirably suited for the purpose.

Seeing that, as compared with the painters, the sculptors are very much restricted in the matter of showing their works, the new gallery ought to serve a very useful purpose. Those who are responsible for the enterprise are clear as to what they want to do. Speaking on the subject, Mrs. Rumsey said: "We have no desire to show sculptures because an artist is fashionable, or because he is in need of help, or for any other reason than this, that the things he models are really interesting."

If this rule of conduct is lived up to there can be no doubt that both the pilgrims to exhibitions, and the artists, will take the Sculptors' Gallery seriously, and that it will put that part of the city on the artistic map of New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now