Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFor the Well Dressed Man

ROBERT LLOYD TREVOR

Clothes for Evening and for Winter Sport and Insignia of the Officers of Our Army and Navy

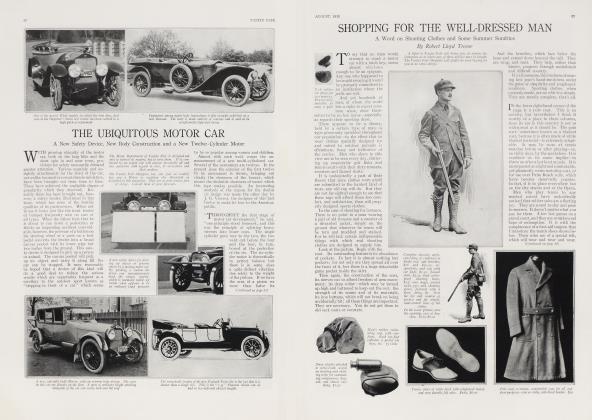

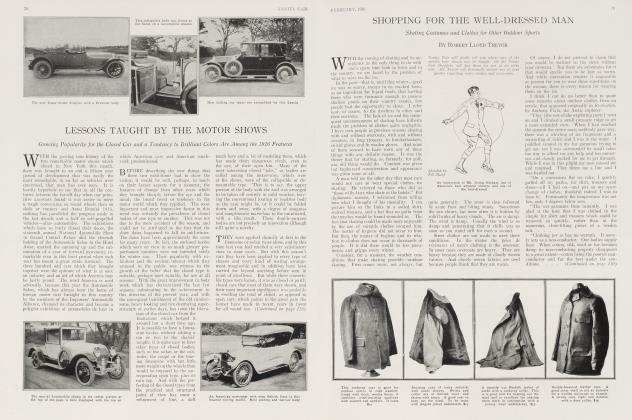

TO the uninfoimed and the careless ones of life, evening dress means only a combination of black and white with two variations; the first a short coat worn with a black waistcoat and black tie, the second, a longtailed coat worn with a white waistcoat and white tie. It is to the very casual observer of this type that the evening dress of the man of today appears monotonous and ugly and it is he, who, if he bothers to think and talk about the matter at all, is apt to long for the coming of some novel fashion or the return of the elaborate costumes of our forefathers.

As a matter of fact, there is nothing drably monotonous about the evening clothes of the carefully dressed man of 1918. They have about them, both in general cut and in detail, the opportunity for a good deal of individuality. A glance at the illustrations on this page, for example, will reveal three quite distinct types of dinner jackets, each of which has features of its own and each of which will differentiate its wearer —in spite of conformity to general standards —from a roomful of stereotyped males.

ONE of these jackets has quite a wide collar and lapels with the points of the lapels distinctly cut. The jacket follows rather closely the outline of the figure and is made with comparatively long skirts. Perpendicular pockets add their touch to the effect of length. The jacket is fastened just at the point of the rather narrow "V" by one button. Another of these dinner jackets is doublebreasted. The turnedback silk facings are made without any cut and are brought together so as to show only a rather small part of the bosom of the shirt. The front of this coat is carried down straight in square corners and there are two slanting pockets in the front part of the skirts and one breast pocket. The coat is worn buttoned to the second button.

Still a third type of dinner jacket has a rather deep shawl collar with the lower part of the facings rounded. This coat exposes a good deal more of the shirt front than do either of the others. The lower parts of the skirts are rounded off and the jacket is fastened by one link button just below the meeting of the lapels. This coat is slightly shorter than the two that I have just described, and is made with two straight pockets in the skirts and one breast pocket. The sleeve, which fits rather snugly, is finished with one button, whereas in the double-breasted jacket, there is a cuff of the same bright silk as the lapels. In the other single-breasted type three buttons are used as a finish to the sleeve. My point in dwelling upon the subtle differences of these three coats is to emphasize the fact that they are all dinner jackets and yet that they have variations, one from the other, which makes it possible for a man to be unobtrusively yet very distinctly differentiated from his fellows.

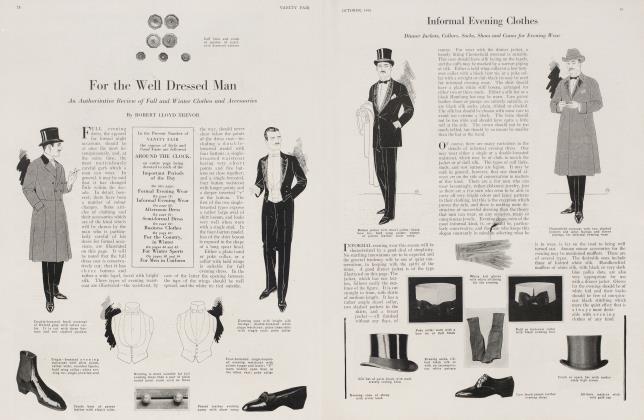

THREE distinct types of collar and of the black bow tie suitable for use with the dinner jacket are also the subject of illustration on these pages. One is the straight or poke collar, worn with a rather long, square-ended black tie, of which the knot is not drawn too tightly. Another is the standing collar with a bold wing, the points of which are long and perfectly square. For this collar, either a single or double - ended black tie of silk or satin, having pointed ends and tied with quite a tight knot, is suitable. The third form of collar to be worn with informal evening dress is a fold or turn-over collar, cut a good deal lower in front than in the back, with square points slightly cutaway and meeting in a sharp reverse "V" at the throat. A rather small round-ended tie, not too long, should be worn with this form of collar.

White waistcoats for use with a full dress coat are also subject to considerable variation. Three excellent types of waistcoats are illustrated in this issue. One is of the doublebreasted variety made with a rather narrow, rounded lapel. It has four buttons and exposes a considerable expanse of the shirt bosom. The waistcoat itself comes to a sharp point at the bottom of its rather long front The second waistcoat is also double-breasted and exposes a similar amount and shape of shirt front, but it has three buttons set rather closely together and the points are cut sharply away, leaving an open reverse "V" at the bottom. It is made with four buttons. The third waistcoat is single-breasted and cut with a smaller opening, exposing less of the shirt front. It has rather wider rounded lapels than the other two vests and is made with four closely set buttons, while the square points are slightly cut-away at the bottom. All of these waistcoats are made in piquet, or in silk.

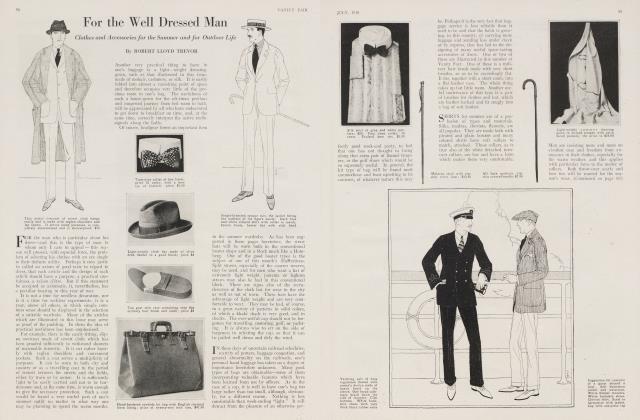

THESE are the days of the sports of blustery old Father Winter; of skating, hockey, snow-shoeing, and the somewhat treacherous ski. Probably the most miserable form of outdoor enjoyment is the Winter sport for which one is improperly clad. I can imagine few less delightful ways of taking one's recreation than to skate on an exposed lake or windy river, bundled up in an ill-chosen assortment of wraps that let the wind in here and the frost in there, until you are all too ready to cry quits. Fortunately in America we are coming to a realization of the fact which has long been established among our British cousins, that to enjoy any sport to the full, one must wear clothing that has been designed to meet that sport's special requirements. It will not do to go out for an afternoon on the ice wearing an old pair of heavy trousers and a nondescript collection of sweaters, coats, and waistcoats, designed for quite different uses than the joys of skating. That is, it will not do if you expect to have a good time, any more than it will do to play golf in the costume of a first-class "hobo."

Some very excellent garments for skating as well as for similar winter sports, are now in the market. They are designed to frustrate the efforts of Jack Frost at the very points at which mere man is usually most vulnerable to his attacks. There is the jacket, for instance, of wool and leather with suede leather sleeves and knitted wrists and collar, which will defy the most penetrating wind, and this fact, together with the elastic quality of the wrist bands successfully defies the efforts of the chilly breezes to get at one's marrow. This jacket has four convenient pockets in which handkerchief, cigarettes, matches, and the like, may be stowed. Another good form of jacket to wear under the Norfolk or skating jacket of cloth, is the woolen sweater coat with quite a wide turn-over collar which can be pulled up very high around the neck and buttoned closely under the chin. Under exceedingly severe conditions of weather this sweater coat can be worn under a coat of leather. Heavy woolen knickerbockers and one or two pairs of thick woolen long stockings would complete this costume.

WITH it should be worn either woolen gloves or mittens or double gloves, the inside pair being of wool and the outside of leather. Two good types of woolen gloves are illustrated on these pages. One of them is made of closely-knitted white soft wool with long wrists, the other is of very closelywoven woolen material bound with either the same material or with leather and fitted with strap fasteners at the wrists to make this particularly tender spot comparatively airtight. An excellent form of headgear to wear with the costume of this sort, especially in severe weather, is a knitted woolen helmet of the same type as that now used by aviators and in the trenches. This sort of helmet covers the whole head and back of the neck, where drafts have such an ingratiating way of creeping down the spine. It leaves only the face, from mouth to brow, exposed, the ears being snugly tucked within its comforting warmth.

There are three forms of skates with shoes attached—which is the only way to have one's footwear for skating comfort—also illustrated in this issue. One is a hockey skate with stout shoe, lacing well down to the toe and strengthened at the ankle. Another is a rather lighter shoe, also lacing far down and used with racing or speed skates of tubular metal. The third is a higher laced boot with round toe and finished plain without any tip, for figure skating. This, of course, is mounted on a rocker skate, especially designed for figure work.

The winter season also affords many opportunities for the enjoyment of exercise indoors, especially in the squash tennis and racquet court. For these games again, one must be provided with suitable clothing in order to enjoy them to the full. A very good shirt for squash, together with trousers of heavy, striped cricket flannel, and some good woolen socks are among the illustrations on these page$. The picture of a well-designed pair of squash shoes is also shown. For these violent games it is very necessary to be provided with warm wraps to put on immediately after play has stopped. This is one of the wise precautions that our British kinsfolk have taught us out of their experience.

BUNDLE up is an excellent maxim and is a sure way to prevent stiffness and lame muscles. A good woolen sweater, preferably of the pull-on variety, is essential. It was the Englishman who first taught us the value of a long coat of blanket cloth or the like to wear between sets of tennis or on the way from the court to the club house. Some men have adopted this custom in connection with their indoor games with the racquet and use coats of this type to slip on for transit from the court to the locker room. A well-designed coat which can be used for this purpose, which is primarily a coat for motoring on milder days, or for outdoor use in that middle season between Winter and Spring, is the subject of one of our illustrations. This coat is made of tan polo cloth and is double-breasted. It has an all-around belt.

With the ever increasing vogue of squash tennis, many men are paying more and more attention to their equipment for the game and especially to their bats. A novelty of the season is the introduction of squash bats with handles and lashings of the colors of the club to which one happens to belong.

WITH the flower of our country's young manhood rapidly getting into the service of Uncle Sam, the number of uniforms seen upon the streets today seems to increase by geometrical progression, and it is more and more difficult for the layman not only to recognize his friend, Tom, Dick, or Harry,

Overcoat sleeve braids, varying from one braid for Lieutenant to five braids for Colonel

when he sees him in khaki or in blue, but to be sure to what branch of the Service he belongs and what rank in that branch he occupies. Uniforms and insignia that no one ever saw before, except those whose lives took them close to army posts or naval stations, are now part of the everyday life of our cities, and as the war touches us more and more nearly and more and more of our own join the colors, we come to have a fast deepening interest in the details of things nautical and military. But the multitude of ranks and services is so confusing that it is a little difficult without guidance to exercise this interest intelligently. I h a v e thought it well, therefore, to reproduce in this issue of Vanity Fair, photographs of many of the insignia of rank and service for commissioned officers in both Army and Navy, and for some classes of non-commissioned officers in the Navy, which apply very generally to men who have joined the Naval Reserve Forces.

One of the very confusing things about the ranks of officers in the Service of the United States, is the fact that while the Army and Navy ranks exactly correspond and their various insignia are to a great extent identical, the names of the ranks in the two branches of the service do not in the least correspond. This makes it very much of a picture puzzle for, the man who has been brought up in the. paths of peace, to straighten out his friends and acquaintances and keep their various positions clear in his mind. The easiest way to remember these various designations of rank is to keep in mind the fact that really they are corresponding. Thus the rank of 2nd Lieutenant corresponds to the rank of Ensign in the Navy, and the typical insignia of this rank in both services is one bar. In the Army, the 2nd Lieutenant wears the single gold bar on the shoulder and one brown braid on the overcoat sleeve, while the ensign wears one stripe of half inch lace on the sleeve of the overcoat and on the shoulder strap of the overcoat.

SIMILARLY, the rank of First Lieutenant in the Army corresponds to the rank of Lieutenant, Junior Grade, in the Navy, and is designated in the case of the Army Lieutenant, by one silver bar, and in the case of his Navy counterpart, by one stripe of half inch gold lace with one stripe of quarter inch gold lace above it. The rank of Captain in the Army corresponds with the rank of Lieutenant in the Navy, the Army Captain wearing -two silver bars and the Navy Lieutenant two stripes of half inch lace. The rank of Major in the Army corresponds with that of Lieutenant Commander in the Navy, the Major wearing a gold leaf and the Lieutenant Commander wearing two stripes of half inch lace with a stripe of quarter inch lace between them. The rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the Army corresponds with that of Commander in the Navy, the Lieutenant Colonel wearing the silver oak leaf and the Commander three stripes of half inch lace. The rank of Colonel in the Army corresponds to that of Captain in the Navy. The Army man wears the silver eagle and his brother in the Navy four stripes of half inch lace. In fact, the same sort of progression holds for the higher officers, Brigadier General corresponding to Rear Admiral, Major General corresponding to Vice Admiral, and Lieutenant General corresponding to Admiral.

INCIDENTALLY, Navy collar devices bear a still closer analogy to the Army insignia, especially above the rank of Ensign. Thus the Navy Lieutenant, Junior Grade, wears a single silver bar with a foul anchor on his collar; the Lieutenant, corresponding, it will be remembered, to the Army Captain, two silver bars and a foul anchor. The Lieutenant Commander, corresponding to the Major, a gold oak leaf and a silver foul anchor, The Commander, corresponding to the Lieutenant Colonel, a silver oak leaf and a silver foul anchor, and the Captain, corresponding to the Colonel, a silver spread eagle and a foul anchor as a collar device.

THERE is, however, a slight mark of divergence between the collar markings of the Navy and the shoulder markings of the Army. When it comes to the question of higher rank. Thus, the Rear Admiral, corresponding to the Brigadier General, wears two stars and a foul anchor on his collar, while the Brigadier General wears one silver star on the shoulder. The Vice Admiral wears three stars and the foul anchor while his counterpart in the Army, the Major General, wears two stars, and the Admiral wears four silver stars, one super-imposed on a gold foul anchor, while the Lieutenant General in the Army wears three silver stars. The rank of Admiral of the Navy, which only one officer can hold, is designated by four silver stars, two of them super-imposed on gold foul anchors, while the rank of General in the Army, of which there can also be only one, is designated by two silver stars with the coat of arms of the United States between in gold.

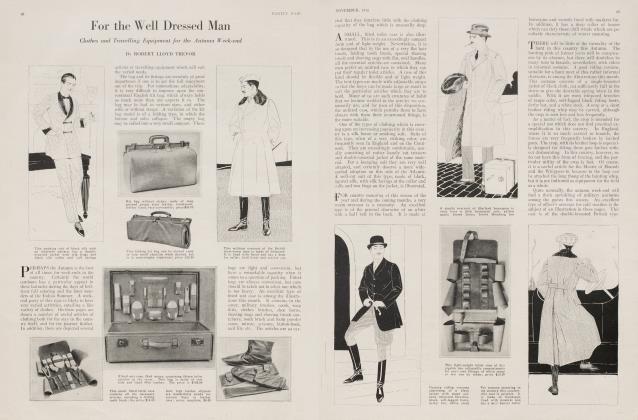

In addition to the more usual insignia, denoting branches of the service in both military and naval arms, I have shown those which belong to officers of services less usually seen. Nearly every one is familiar with the fact that two crossed muskets indicate Infantry, two crossed sabres Cavalry, etc., but to a citizenry unused to war, the insignia of the many supplementary services, such as the Adjutant General's Department, the Medical Corps, the Quartermaster's Corps, and the petty officer's marks in the Navy, such as Boatswain, Chief Carpenter, Chief Pay Clerk, etc., are entirely unfamiliar. No attempt has been made to include the insignia of the aviation service because these insignia are to some extent still undecided. It may be said, however, in general, that for this branch of the service when officers have attained the grade of Military Aviator they will wear a device on the left breast embroidered in silver on a blue background, the insignia to be two wings with a shield between and with a small five-pointed star above the shield. The Junior Aviator will wear, similarly, the same insignia with the star omitted. Observers will wear the shield with a single wing at the right of the shield. In addition to this distinctive marking aviation officers of the Army wear on their collars, the crossed flags of the Signal Corps. As to Naval aviators a device will be worn as in the case of the military aviator, on the left breast, It consists of a winged foul anchor with the letters U. S.

THE branches of Army service as indicated by hat cords are also of interest. Thus, the campaign hats of all officers above the rank of Colonel have solid gold hat cords. Other officers of all arms of the service wear gold and black hat cords except officers of marines, who wear a cord of red and gold. The colors of the hat cords worn by enlisted men, including non-commissioned officers, designating the arms of the service to which they belong, are, Infantry, light blue; Cavalry, yellow; Artillery, red; Signal Corps, including aviators, orange and white; Engineers, red and white; Quartermaster's Corps, buff (of a salmon shade); Medical Corps, maroon and white; Ordnance, red and black.

BY means of these various insignia it is possible to tell at a glance exactly what branch of the service one's friends belong to and to know, also, their rank and station. One rather confusing matter, however, is the lack of corps marks on the overcoats of officers of the Army. No distinguishing marks, such as those which are used as collar ornaments, are worn on the overcoats; only the rank being indicated by the braidings. It has been suggested that this was a matter which should be rectified by the War Department, but as yet no action has been taken on it. In the Navy there are distinguishing marks for the corps. Thus medical officers wear dark maroon velvet; pay officers, white cloth; naval constructors, dark violet cloth; dental officers, orange velvet; professors of mathematics, olive green cloth, and civil engineers, light blue velvet.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now