Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Soldier of the Legion

A Type Developed by the Greatest Romantic Period of History

JOHN JAY CHAPMAN

IT is illustrious to be alive during the great war. For what mere accident of life would any man exchange this good fortune? For wealth, position, success in any other age? What? And miss this, the greatest romantic experience of mankind, the gate that divides history like a triumphal arch, so that all that went before it becomes antiquity and what is to follow is futurity?

We stand on the top of the arch and are half deified as we look in either direction toward the past and toward the future of mankind. The people who went before us have become remote and a little estranged. They are interesting, as the ants are interesting, or as Miss Austen's studies of provincial English life are interesting.

Take up Rose's Life of Napoleon and see how the great issues have shrunk. The treaties, the Ambassadors, the intrigues, the burning questions of Europe seem like the past bickerings of some parish vestry. And they are recorded also in such detail, and with so much pomposity. Will men ever again be able to deceive themselves into so solemn a belief as to the importance of their own historic knowledge? We at least who have lived through the great disillusionment of 1914, where everyone received a surprise, can hardly be expected to take diplomatic and documentary things very seriously hereafter.

We have seen things happen in two hours, which generally take two centuries; and the relation between events and historic evidences has been such that a cabman's opinion was as valuable as that of Lord Acton. Mother-wit counted for everything; book knowledge for nothing; learning was almost an impediment. The historian, or the educated person, has been rather embarrassed than aided by his acquired cleverness.

Why, we have assisted at a world-drama with a thousand scenes, each one more rapid and thrilling than the last, while we clung to our seats and screamed with every emotion of which the heart is capable,—love, joy, terror, anguish, triumph, and pure intellectual excitement. Surely, so far as emotional experience goes, we may die content. We have seen life.

AS for posterity, one is almost tempted to be sorry for it. There is going to be a long period of rest, rationalism, and recuperation. Excitability will be bad form, war taboo, the police-force everything. A dead millenial calm will set in, bringing a weariness of life for those who demand heroic emotion, and a heaven for plodding mediocrity. The problems to be settled will be moral, economic, administrative,—dull, decent arrangements which will require and will generate good drudges.

The survivors of the heroic present will perhaps live to be regarded as bores,—laudatores temporis acti,—just as the old duffers of our G. A. R. lived to become a sanctified nuisance, as the Garibaldians became an infliction, as the acknowledged saviours of society have done in all ages.

These chaps never get tired of themselves; and our new world-savers will be fifty times as self-centered and a hundred times as prevalent as any veterans of the past. You will find them at Jerusalem and Hoboken, in the Caucasus, in Thibet, on Mt. Ararat,—prosing about the great days of old. Dear me, dear me, is it true that we have eaten the cake of human experience, so far as romance goes; and that nothing is left for later generations except the box and the label? I hope not.

Perhaps it would be wise in us to remember the danger of self-glorification which always fringes success, and to keep a cool head and a sense of humor even in our hallelujas. It is against ourselves that we must be warned. The heroic will never die out among men; and if we have lived in an epoch when heroism were common and when inspiration seemed to descend on men in all ranks in society, this ought to teach us how nigh to glory is our dust, not now merely, but forever.

The man to whom I feel impelled to put up a little tablet, was one of the humblest of that type which never changes, but only reappears among men: the soldier hero.

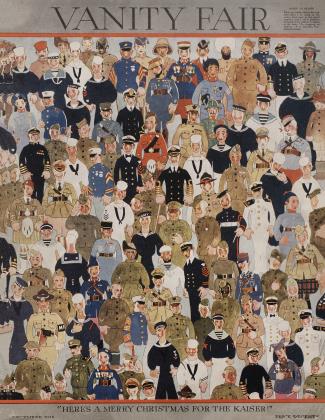

AT the outbreak of the war, the French Foreign Legion was among the most romantic institutions of the world. It had always been formed by voluntary enlistment from men of all nations. No questions were asked. The fighting body was thus made up by natural selection from the daredevils of the world: Poles, Jews, Greeks, Russians, Spaniards, Turks, Croats, Scandinavians,—even Germans were in it.

And, of course, joining the Foreign Legion was not the first but the last thing a daredevil was apt to do. He was a man who had loved excitement in his youth and had tried many kinds of life. He was the rolling stone, the Gil Bias, the d'Artagnan, the Casanova, the very type of man on which one whole class of fiction,—the tale of adventure,—is founded.

The Legion was, of course, always filled with men who had tried many trades. Such a collection of people as Cervantes or Bret Harte would have rejoiced in were at all times to be found in it. The romantic spirit of such men is always akin to heroism, as the traditions of the world have shown. And now add the great fact that Germany's attack on Belgium made the French Foreign Legion a focus, an arena, where the natural born fighting hero, the true knight, the inspired adventurer could come into personal touch with the issue. He could do this immediately. To volunteer in a foreign army for the sake of a cause which is universal is the most obviously heroic thing that a man can do in this world, and the flag of the French Foreign Legion became an honored and glorious symbol of the great issue.

AMONG the millions of men in Europe whose clock struck when Belgium was invaded there were a good many truly heroic and religious natures, direct, vital men—and I don't know how many thousand of these joined the Legion. Its ranks probably held more individual enthusiasts than any army since the crusades; and its record in the war,—the extraordinary honors it has received and the reverence which its name excites in France,— bear out the probability.

Daniel William Thorin, who died of consumption in the Sister's Hospital at Prescott, Arizona, on September 27th, was a typical son of the Legion. He was born of Norwegian parents and spent his boyhood in our Northwest. Thereafter he followed the sea, somewhat after the fashion of Kipling's rougher characters, and he had stories about sailors' lodging houses, mutinies, impressments, escapes, murders and drunkenness in every part of the world.

He spoke with a quaint accent, a shrewd, half-conscious humor, and the long practice of a natural raconteur, which drew men to a circle when he began, and fascinated them with the gift of the ancient mariner. Yet at any moment Thorin was apt to cease talking with a smile and an odd look of surprise at finding he had talked at all.

There must always have been a divine spark in the man, that spark which we miss in Kipling's heroes and find in those of Bret Harte's. This found expression in the reason Thorin gave for joining the Legion,—"I got to thinking it over, and I saw it was my fight"; and again in a letter he wrote before one of those attacks which gave the Legion its fourragere,—"I am going into battle to-morrow to do what I can to keep the Boches away from you and little Kate. If I come out, I'll write to you. If I don't, so long, God bless you." You may take it for granted that events do not make men, but only grind them down till the original elements become visible.

Continued on page 80

Continued from page 23

THORIN was among the early volunteers in the Legion and was noted as a tremendous fighter and heavy drinker, for disregard of his personal appearance and for a wild uncontrollable humor which no circumstances could quell. He was. one of those men whose demeanor is the same in whatever company they find themselves, whether of princes or paupers,—a spontaneous person. He was twice gassed and several times wounded, and during his furloughs at Paris he came under the motherly attention of Mrs. Weeks, who had lost a son in the Legion and who for three years made her Paris home into a shelter for the American volunteers and soldiers. It was through her that I came to know Thorin.

In the autumn of 1914 and after a good many months in a hospital in France, Thorin was sent back to America to die of consumption brought on by the gassing,—naturally without a cent in his pocket.

Legionnaires, of course, receive no pensions. Certain friends of the Legion became interested, in him and he was sent first to Phoenix and then to Prescott, Ariz., in both of which places his spirit evoked a recognition. The Sisters of Mercy at Prescott took good care of him, and other friends appeared at his bedside,—the Minister of the Congregational Church, the bank president, whose letter is quoted below. Thus he died, as it were, with the angels bending over him.The appearance of this little group of good people is a touching proof of the spirit now reigning everywhere in our country.

I must add that when I first met him, on his arrival in America, the external roughness had left Thorin. He was noticeably and surprisingly clean, neat, modest, not exactly apologetic, but with that shyness which is often seen in great fighters. He must have been fundamentally a selfless person and during the last months of his life, as the outer world receded and became dim, the two strongest features of his character, courage and gratitude, were the only ones that survived. So this roughest of all men appears on his death-bed as a typical hero.

I EXTRACT a few lines from his letters in the hospital (for he was a great correspondent), and I give the whole of the last one: _

Prescott, Arizona, July 21, 1918.

I forgot to thank 'you for the newspaper you sent along. Good news. I think the Kaiser has had his day. Oh, believe me, the Fritzies are very tired and would like to see the war finish right now. No, give them no rest, drive them back. Let them have a taste of Belgium and France. I guess you heard of the two Irishmen fighting? Well, before they started they came to an understanding that when one was down and said he had enough, they should let one another up. An old gent was going to see that everything went shipshape. Well, the scrap started, and after a while one was down, hollering "enough." The more he screamed enough the more the other hammered on him. The old gent thought it was time to interfere, so he said to the best man on top, "Why don't you let him up? He has said enough." Paddy winked his eye and answered, "That's alright, Pal, but this fellow is such a liar that you can't believe him." So it is with the Boches, you can't believe anything they say. So just do like Paddy, hammer on.

August 24, 1918.

Well, I am still among the living, but that's about all. Everybody thought I was a goner all last week. I wasn't on the earth at all. I had all kinds of funny imaginations; but sometimes the pain brought me back. I am awfully weak but I don't intend to give in. I will fight as long as I can move a finger. I had a pretty good night and that makes me feel better this morning.

Mr. Cocks and his wife was in to see me the other day. I was ashamed. I guess they thought I was looking dirty because I haven't had a shave for over three weeks. I got a razor but I can't use him, too shaky, never mind, that's the least of my troubles. * * *

Well, things seem to go fine, the Hun is on the run, and I hope the Allies will keep him on the move. It does me good to hear he is getting it on the neck, we were the goat long enough. They used to call U. S. soldiers feather-bed soldiers, but I would like to see the one that calls them that now. They have certainly proved themselves, good luck to them. * * *

September 6, 1918.

I am sick unto death, but I can't part from this life before I give you my last greetings. .

Well I guess I will soon be over the top for the last time, my only regret being not being able to see you folks before I charge. Mr. Hazeltine is going to see to my funeral. He is a good fellow. Well, folks, you that have been taking my parents' part for nearly a year, I salute you and thank you, and my last dying breath shall be a blessing for you all. ,

Good bye. Yours thankfully,

BILL THORIN.

The following is from Mr. Hazeltine:

September 16, 1918.

"We were over to see Thorin yesterday. His gratitude to you is very touching. He has been regretting the fact that he did not die on the battlefield so that he might have had some of the glory due his sacrifice, and Mrs. Hazeltine had the happy thought to ask the Commandant of the Post nearby if Thorin might not have a military funeral. Arrangements have therefore been made for a squad of regular soldiers to act as escort and the body will be conveyed to its final resting-place on a caisson and the coffin draped with the Colors in true military style. The Colonel called on him and promised him these honors and the tears streamed down his face from very joy."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now