Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

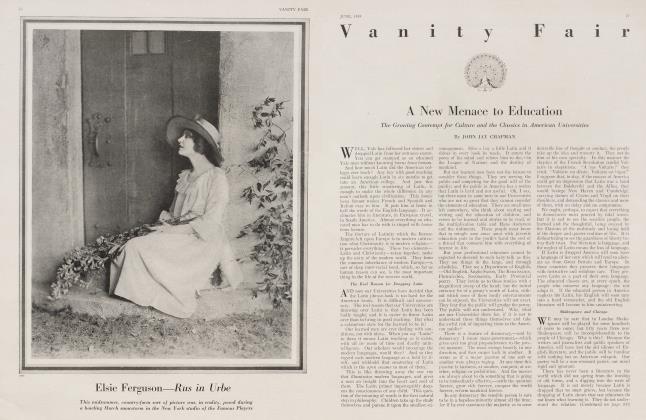

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHighbrows, Guttersnipes and Tax-Payers

The Results of the Divorce Between Learning and Talent in America

JOHN JAY CHAPMAN

LEARNING, talent and wealth,— all three of these are required to make anything that can be called civilization; and it is not so much the existence of these elements as their harmonious mingling that brings art and poetry to birth.

Tradition, genius and a paying public meet in any work of art. For whether an artist be a ballad-maker or a sculptor for the Parthenon he must have had some original gift for his business, he must have a training in the craft and he must be kept alive by an appreciative public. The thing which comes out as a work of art is the result of three elements,—gift, craft and money; and before the work itself appears, these elements must have met somewhere in a studio or at a club or a tavern, and must have become fused in a few temperaments which the currents of life have jostled together. .

The Universities and Academies ot any country are places where its traditions and its learning are kept alive; they are the formal and disciplinary part of art. The fledglings of new talent must have passed under the wings of tradition or they cannot perform well. And it is obvious that the general public supports both the colleges and the fledglings. The Taxpayer pays the piper, pipe he well or ill.

I shall leave the Tax-payer in the background for a few moments, and speak of the two creative elements in art, the learned part and the personal part, calling each of them by the nickname which it at times receives from the other in America; for it is a dreadful fact that learning and natural talent in America have become separated and hostile to one another. They have hardly any points of social contact, and yet social contact is the only salvation for each of them. Social contact is the raison d'etre of both.

"Highbrow"

THE word Highbrow was first hurled by a Guttersnipe at a plaster bust of John Milton, which stood in the sanctum of a High School. The word signifies intellect divorced from social intercourse, and calls up in our minds the image of a scarecrow. The word is used by the illiterate to vilify education; and it stuck to our college professors. It hit a rift in our social structure. It spoke a whole volume about Learning in America. It gave a clue to a riddle which is profound and baffling, and which is indeed one of the eternal riddles of human society,— What is it that makes people talk, sing, paint and write, eloquently? Where is the heart and focus of the fine arts? What is the charm which the old world possesses and which we seem to have lost in America? These questions surge in our minds wherever we hear the word "highbrow", and we wonder why education should be regarded as a bogey.

There are a great many intelligent people scattered over the United States, but they seem to be "islanded". Two of them will live all their lives in the same town and yet never discover each other. In Europe the mental channels of communication between men are as old as the Roman Empire, and mind flows into mind, talent into talent. There are Inns along the highways, and if you set a penniless playwright dow'n in London he will be apt to find a friend within a week—not an audience, perhaps, but a friend.

In Europe the entomologists have their lairs and the mathematicians their runways. There are little booths and shelters for priests and actors; for amateur photographers, alpine climbers, archaeologists, theosophists; and indeed you cannot in Europe be in earnest about anything without finding social and moral support at your elbow. The learned professions there are mortised into the popular life by a thousand personal ties, traditions, associations, meetings, ceremonies, pieties,—all of them floating in an atmosphere of warm social intercourse.

The Difficulties of Importing Culture

IN the old world the brain of a nation (which for the moment we might call its traditional education), is kept in touch with the heart of the nation (which we might call the new talent) by an inherited system of waterworks that nobody thinks about. Thus, the European guttersnipe has no quarrel with learning. He respects learning. He takes to it as a duck takes to water; and thus the soul of a nation becomes unified. Villon and Heine are outcasts and revolutionaries to be sure; but they are not in revolt against learning. They find themselves at home in their world of intellect from the time when they break the shell.

The force which keeps the sluices open to the young duck in Europe is social and personal; intellectual, of course, but not forbidding. This is the secret of Europe, and the strange thing is that whatever treasures of bric-a-brac or cultivation our clever people bring back from Europe, they never seem to import this mystery. They return to us the more highbrow and the more academic and isolated, the longer they are exposed to the humanities of old Europe. Evidently the sacred drug, or whatever it is, must be discovered and developed upon our own shores; for it does not bear transplantation, but turns into a sort of poison in the steamship cabin on the way home.

There is, however, this much to be said about drugs and charmed chemicals,—that while they are difficult to discover, once found, they are potent: a little of them does wonders: and the elixirs reproduce themselves. If we can develop a little social intercourse of the right kind, in which the three elements of art are naturally, and almost unconsciously mingled, we shall have the seed.

The chasm which now yawns in America between the highbrows and the guttersnipes will not be bridged in a night: perhaps a couple of generations must be spent in bridging it or filling it up. slow, because it can only come about through the enlightenment of the Taxpayer. And now it is time to say a word about this party on whom so much depends. You will observe that the Tax-payer goes on existing whether the other two partners exist or not; but they cannot neglect him for a moment. They must provide him with something that he will pay for, or they perish. And, therefore, they both labor eternally over this booby, trying to educate him and to keep themselves alive at the same time. Learning gets into Tax-, payer's pockets by appeals to his prejudices, by submission to his ignorant whims, by persuading itself that whatever the Tax-payer will pay for, if the thing be only called a college, must therefore be a part of the higher education.

(Continued on page 116)

(Continued from page 47)

Of course, Learning, in presenting herself to the Tax-payer, must pretend to be a thing that he can understand. She is obliged to fish something out of the Tax-payer that shall be dubbed a University, even though it turns out to be a canning factory, a cash register or a social bureau. Her emissaries adopt the manners of serious commercial men; for they meet the Tax-payer at his desk. The relation of Learning to cultivation and the fine arts, is no more thought of than her relation to the moon. And the older professors who continue to preside in colleges which have lost their character take on a hungry look and are supposed by everyone to be interested in things which are not of the smallest importance. They are our Highbrows.

Pulling the Tax-Payer's Leg

WHILE this course of things is in progress the Guttersnipes on their side get into the Tax-payer's pockets by feeding his vanity and his taste for luxury with obvious amusements,—operas, short stories, horse-play, Titian's pictures, splendid pageants, bedroom farces,—with anything, in fact, that will keep him amused. For the Guttersnipes, you understand, meet the Tax-payer after dinner. And the poor Guttersnipes provide these entertainments at a tremendous cost to their own natural talents, and often through a betrayal of their own God-given trust. It seems as if the whole process of pulling the Tax-payer's leg were a mere succession of sacrifices through which both the Highbrows and the Guttersnipes were corrupted.

Such are the ghastly results of the divorce between learning and talent in America. We see these results on the great scale; but they are to be cured on a small scale. Social phenomena are not visible till their causes have been in progress for a generation or two, and then certain great features stand out like cliffs in a landscape. This is because a river has been running for many years and has cut the crags apart. When this point has been reached, people begin to reason about society, and wonder how they can bring these cliffs together again. It would, however, be a very fatuous project to bring all our learned professors together in Carnegie Hall and face them with the actors, artists, painters, singers and poets of America,—even if you could get a Tax-payer to pay for the hall.

But, wherever you have a small group of socially inclined, intelligent people, cooperating to do something for their own entertainment, filled with respect for the part and using such talent as they can lay their hands on, you have the beginnings of art and literature, and though the vision may rise in the fotm of a charade, the elements that gave rise to the Greek drama are in the room.

It is the social element in which America is weak. The greatest loss we suffered by being separated from Europe has been a loss of the power to play. What I have against our highbrow is that he is serious. What I have against our humor is that it is serious,—too much purpose, too much edge everywhere. There is too much edge and purpose even in this paper; but I must make my bow to the subject before I die:—call the Highbrow and the Guttersnipe into a circle and bid them shake hands, while the brutalized and much flattered Tax-payer is invited to place himself in a corner, keep his eyes open and see whether the other two can't do something to make him sit up.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now