Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPortraits and Portrait-Painting

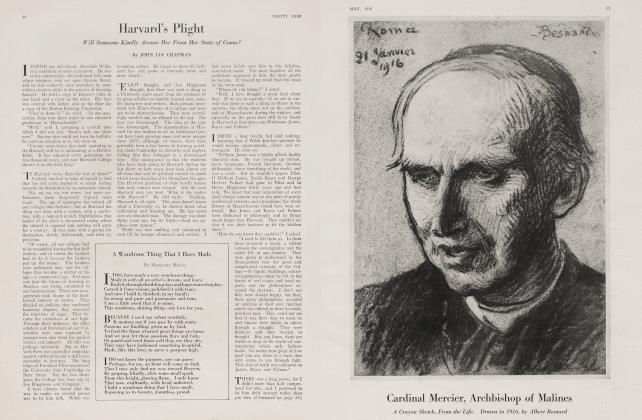

The Gradual Transition from Art to Realism since the Days of Van Dyke and Sir Godfrey Kneller

JOHN JAY CHAPMAN

IN the old days before the plastic arts became self-conscious, people who could afford it had their portraits painted as a matter of custom. This was done partly as a record, and partly as decoration,—as furniture or a slight addition to the luxury and comfort of their household, like a new rug, or a sundial on the lawn. The decorative function of portraits prevailed over their other meanings, and people were satisfied to have a handsome thing, done in the style of the day, and they did not worry themselves too much over the questions, "Is it art? Is it a good likeness? Is it my best expression?" etc. The traditions of the day, or, one might say, the taste and fashion of the day, enveloped the whole matter and carried the individuals along in their current. I don't suppose that the women of Charles the Second's time looked so much alike in real life as Sir Godfrey Kneller made them look on canvas, or that all of Van Dyke's gentlemen had the exquisite Van Dyke look. As for Sir Joshua Reynolds and Gilbert Stuart and Raeburn, they each had a symbolic robe for their sitters, and the sitters came to the painters in order that the mantle might be thrown over their shoulders and they might go home carrying off something handsome for their front halls.

The Age of Realism

NOW the strange thing is that this decorative side of portrait painting was, so far as the sitters went, largely unconscious. The age was using the artist and the artist was using the sitter, to make something beautiful. When photography and the mechanical arts of the nineteenth century came in, and the old hazy artistic atmosphere became thin, when the outlines of life grew hard, and art criticism became a profession, and the custom of having one's portrait painted gradually died out, then the unconscious authority of the painter was obliterated. The decorative function of portraits was forgotten. The public strove only to preserve a likeness of the individual sitter; and the striving defeated its own end by creative hateful objects,—enlarged crayons, images and mortuary mementos, which became a grief and a problem to the household in the next generation.

Now-a-days the sitters come at the painter with poker and tongs. It is a great experiment to have one's portrait done:—"Can you get John's expression? What we want is a likeness. We think it rather a foolish expense anyway, but Aunt Nelly wishes it done."

The painter, too, has lost his controlling tradition. Shall he do it in the style Velasquez or in that of Franz Hals? The painter is almost obliged to become an eclectic. He hasn't had enough practice to develop a style of his own; and he therefore experiments. The question of style used to be settled by a tacit understanding between sitter and painter. It is a thing too subtle to be described in terms of demand and supply, yet it is a thing which all the older portraits record so accurately that a child can feel it. It is everywhere in the picture,—in the costume, in the expression of the eye, in the proportions, coloring and setting; and it dates the canvas even to a decade. Thus felt the world in 1840; thus in 1640. This is the part of the picture which was prescribed bv the epoch. The age wrote its own secret clauses into the painters' contract when it gave him the order, and would not accept his canvas unless it glowed with all these qualities and conventions, which are indeed seven tenths of the whole work.

The Need for More Portraits

THE final shaft of beauty which we all hope for in a portrait is of decorative, impersonal, popular origin. I would not disparage those excellencies which only the expert can see; but I am speaking for the moment of something that everyone responds to, in the traditional, the expected, the historic element, which fits the picture to the wall and is like a strain of familiar music in itself. This element comes from the domestic side of art and is brought to the painter by those who love beauty in their household surroundings.

During the last sixty years while art was becoming a faint and subsidiary influence in social life, it has been kept alive by the Academies, and the painters themselves of to-day are like very competent law students seeking practice, or like threshing machines in search of a field of corn. It seems to me as if I knew ever so many painters who needed only the pressure of work to make them competent portrait painters. I feel an impulse to get up a society in which everyone shall agree to be painted. But I know this idea is merely a reflection of the advertising mania of the present age which thinks that anything under the sun can be accomplished by getting up some society. The bridge between the academy and the popular in art must be formed gradually. It must spring across the gulf by a magic of its own.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now