Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

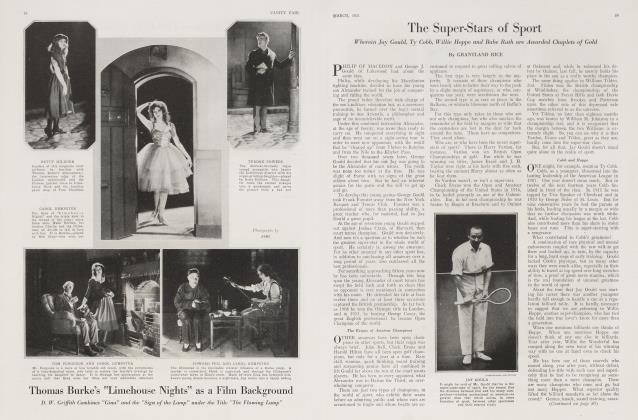

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOnly Spectacular Golf Could Win

Some of the Sensational Dashes that Marked the American Open and Amateur Championships

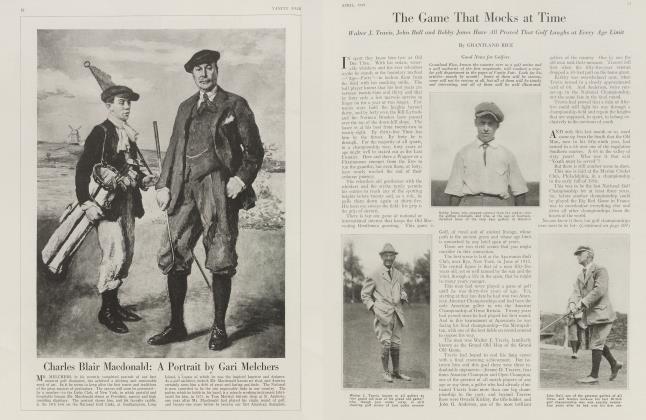

GRANTLAND RICE

WHAT with two million rabid and rampant devotees and divotees to pick from between the ages of sixteen and sixty, the proposition of winning a golf championship on American soil has become highly involved with any number of complex and complicated streaks running back and forth.

These complications have resulted from the great growth of the ancient game, the big improvement in courses and the still greater consequent improvement in average play.

In looking back over the two big championships of the waning season, the Open at Braeburn in Massachusetts, and the Amateur title hunt at Oakmont in Pennsylvania, one fact stands out, viz., that merely steady and consistent golf is no longer good enough to win—that only those golfers capable of sensational dashes or par-beating romps under the main test have any chance to arrive at the ultimate summit and have their moist brows arrayed in a select chaplet of olive and laurel.

With such widespread class giving battle for the main prizes, only those .capable of super-golf seem to stand any chance. The game has therefore reached the slash and take-a-chance stage where the entry who doesn't is likely to find himself slogging well behind, however steady he may be on the more conservative side. In fact, conservatism is no longer an attribute of the successful golfer.

A Historic Match

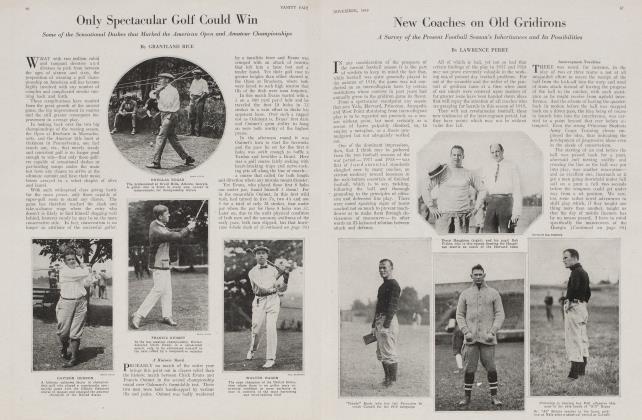

PROBABLY no match of the entire year brings this point out in clearer relief than the historic match between Chick Evans and Francis Ouimet in the second championship round over Oakmont's formidable test. These two men were both handicapped by various ills and pains. Ouimet was badly weakened by a tonsilitic fever and Evans was crimped with an attack of neuritis that left him a lame foot and a tender hand. Yet their golf rose to greater heights than either showed in the Open at Braeburn, where both were keyed to such high tension that ills of the flesh were soon forgotten.

In this match Evans started with a 3 on a 480 yard par-5 hole and he traveled the first 18 holes in 73 strokes in a vain effort to shake his opponent loose. Over such a rugged test as Oakmont is, Evans' first dash and Ouimet's grim ability to hang on were both worthy of the highest praise.

In the afternoon round it was Ouimet's turn to start the fireworks and the pace he set for the first 8 holes was swift enough to baffle a Vardon and bewilder a Braid. Here was a golf course fairly reeking with heart-breaking traps and nerve-racking pits all along the line of march— a course that called for both length and direction where any mistake meant disaster.

Yet Evans, who played these first 8 holes one under par, found himself 3 down! For in the meanwhile Ouimet, in this first wild rush, had turned in five 3's, two 4's and one 5 for a total of only 28 strokes, four under par where the par for these 8 holes was 32. Later on, due to the unfit physical condition of both men and the uncanny swiftness of the early pace, both men slipped, but that hurricane 8-hole dash of Ouimet's was just sufficient to underwrite his later lapses and to bring him home by the margin of a single 8-foot putt. It was an episode of American golf that reflects credit upon both men, credit to Ouimet for the miraculous pace and credit to Evans for his ability to battle on undismayed until his chance came later to square the match.

(Continued on page 96)

(Continued from page 66)

The Herron Highway

WE return now to the point that it no longer belongs to one of the highly advertised stars to launch any such drive. In an earlier issue of this magazine we pointed out the fact that any one of the younger golfing set might at any moment step forward with golf capable of stopping an Evans or a Ouimet.

This performance fell to the lot of young Dave Herron, an unknown factor in championship golf, an entry who had never qualified but once before.

Herron, in his afternoon round against Bobby Jones, played golf almost as spectacular as that 8-hole march of Ouimet's and over a much longer distance. Herron played the 13 holes that were completed in the final round in exactly SO strokes against a par of S3. Jones, playing par golf, found himself drifting steadily behind.

Take your own case, rough or gentle reader. Suppose you had keyed your game to such heights that you were able to strike off par after par over a championship course, making no mistakes as you pressed steadily forward only to find yourself near the finish 3 or 4 down! Yet there are few entries in our championships now who do not have to look forward to just such annoying episodes and incidents. The old days have vanished into the mists when the more or less unknown and inexperienced were almost certain to break under the big test. Travers used to say that against a younger opponent he was never bothered about being a stroke or two behind because he could afford to wait until his antagonist came back to meet him. No golfer can take this chance now or move forward in any such serene contentment.

Take the case of Dave Herron. In match play he had known but one championship before this 1919 affair. Yet in his final round against Bobby Jones, one of the most brilliant golfers in the United States, Herron was as cool and as calm and as collected as Travis or Travers might have been when at their best. An expert might say that his back swing was entirely too fast to stand the pressure of a hard match, for Herron comes back in a flash. Yet he played steadily along with a serene certainty of victory where to any one not knowing all the facts he might have been a veteran of a dozen hard fought championships.

The Week of "On Your Game"

TAKING away no credit from those who survived the rugged tests at Oakmont, the Amateur Championship has now become a matter of survival for only those who for that week are on their game. The star and the duffer alike know the elusive nature of this sport. One week you can—no matter what club you use. The next week, with no apparent reason in sight, you can't, no matter how you try. There are no explanations to be offered for this sudden coming and passing of confident golf. A man may be physically unfit and yet be at his best. He may be physically perfect and yet be far off in his co-ordination and his timing. He may step confidently forth expecting to play the best golf of his life and suddenly find that he is playing badly with every club in his bag. Why?

For no reason that he can find. It is largely because his mental and his physical powers are not co-operating, but this is no reason that leaves a cure in sight.

Few golfers in the land had turned in more consistently brilliant scores between May and August than Oswald Kirkby, the Metropolitan championship. Over thirty or forty courses in the United States and Canada he had ranged steadily between 71 and 74. He had been playing better and sounder golf than at any time in his career. Yet on the day of the qualifying round at Oakmont where he was picked among the first four from the big field, his game suddenly went to smash and he was unable to turn in a pair of 86's. The same fate befell others—such fine players as Perry Adair, who had a 73 the day before; Harry Legg, the Western Champion; E. M. Byers, ex-National champion; Jesse Sweetser, the young New York star, and still others capable of turning in scores around 75.

If a golfer is off his game before a championship he may easily, through coaching and practice, get back on again. But when he starts in a championship test and finds after a few holes that he is all off for that day he has but one recourse left—and that is to refrain from over trying, to hit with less effort—and trust the rest to fate. He is simply up against a turn that only the favored few can overthrow.

It is our belief that over a long stretch and over all types of courses, Francis Ouimet and Chick Evans are the two best amateurs in America. Yet this may mean but little during championship week if either is a trifle off and someone else is on, a development that has assailed both more than once. For there are now too many star young golfers around the landscape who may be at the top just at the critical point for even Ouimet or Evans to be a trifle out of gear.

For wonders, in a championship, will rarely cease. Dave Herron found himself in the same bracket with Evans and Ouimet and yet he had to play neither for both were gone before he had his chance. And the next championship will find an even larger and better field with the growth of golf under such headway. The youngsters are getting more experience and their game, under competent instruction and over test courses, is coming forward in every section of the country. Hereafter, more than possibly, one can only win as Herron did by playing the best golf of the tournament from Monday morning through Saturday afternoon over a six day span.

In the Open Championship

NOT only were spectacular dashes featured in the Amateur championship, but one of the most spectacular of them all was required to bring Walter Hagen to the top again in the Open.

Standing on the 12th tee of the final round he received word that he must equal a hard par to tie Mike Brady who had finished the 72-Lole journey with 301 strokes.

Hagen then hooked his tee shot out of bounds. This mistake would have jarred the nervous system of the most redoubtable. Hagen accepted it as coolly as he might have taken a cigarette. "Oh well," he said, "I'll let that go as a missed putt and get it back." And from that point on he moved along with a mixture of steadiness and brilliancy that deserved success.

The golfer who wins in the big tests must not only have the game but he must be a staunch believer in his own destiny. If he lacks this faith his downfall is only a matter of a round or two.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now