Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Little Soviet

One of its More Serious Members Explains How it Works in an Apartment House

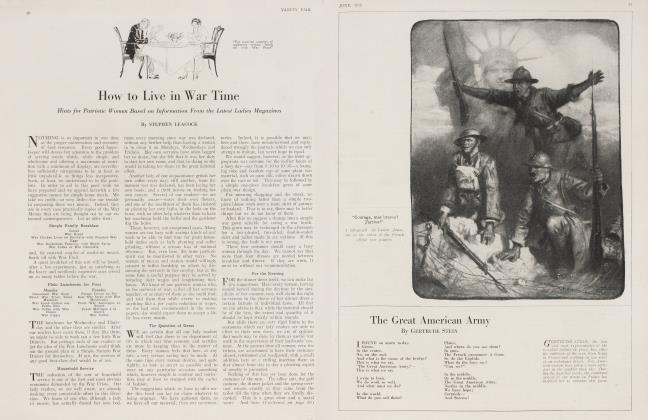

STEPHEN LEACOCK

MY friends and I have just started a little soviet of our own. Of course, it's a modest little thing at present, but we are hoping that it will grow. A really good soviet has to be organized, so we understand, in unit groups of half a million harmonious persons. And we couldn't get so many as that. They are harder to find than one would think until one gets into sociological work of this sort. So we had to begin on a small scale.

We have written to Comrade Lenine in Russia about our soviet and we got back just the nicest letter. He said he kissed us all. Imagine it. And he said he wished so much he had us all in Russia, if only for half an hour. He implied that a half an hour would do. But all our members are too busy at present to start. Later we are going to send two delegates. We have our eye on Mr. and Mrs. Rubenstein for it, but they don't know this yet.

The way we came to get the idea was by hearing so constantly about the way in which the soviet is working, and the great things it is doing. I had a friend who belonged to the same mandolin club that I did and who always used to say whenever things went wrong: "Now under Soviet Government this kind of thing couldn't happen." Another friend of mine—he was in the Pullman Car Company till he had to give it up, owing to friction—has claimed for years, that, if the railroads of this country were run solely in the interests of the men who run them, they would run them to their own satisfaction; but as long as the cars are cluttered up with a lot of people riding on them and yet having no interest in them beyond riding on them, they can't expect it to be as it otherwise would. I don't know whether I make the argument quite clear, but anybody can read it all, only much better expressed than that, in the little Comrade's Handbook of the Soviet that we use.

Comrade Globenski

WE got our opportunity to begin owing to the fact that several of us were acquainted with Comrade Globenski, and he told us how, and offered to be dictator. Comrade Globenski used to mend shoes on Grand Street, but he said that he had grown sick and tired of the capitalist regime and bourgeois society. He said he had no wish to take part in capitalism any more.

So, when we had heard so much about the soviet, and what it could do, we went to Globenski, three or four of us, and we said: "Globenski, do you know how to make a soviet?", and he said: "I do." So we said: "How much will you take to make a soviet for us ?", and he said: "I will take nothing. The soviet is based on love. I will do it for love." Then he got up from his bench and kissed us. It was wonderful.

The commencement was simple. Most of the prospective comrades lived in the same apartment house, so we simply sovietized the house and declared it to be the common property of all the brothers and sisters. Globenski spoke to each of the other tenants and, after he had spoken to them for ten minutes, they were willing to move out and let our brothers and sisters move in. After that, all the house became one home and our life under the soviet had commenced.

Globenski invited the proprietor of our apartment house—if I may be allowed to use a term which ought to have no place in the language—to become a member of the soviet himself. This would cut out the cancer of rent, which otherwise,—I am quoting from the Comrade's Handbook—would eat into our vitals. But so far, he has refused to sovietize himself. But this is a matter that will right itself. Some of the comrades talk of getting him into the cellar on a dark night and sovietizing him with a piece of gas-pipe.

But imagine the striking change of life which our new communal method affords to us all. Instead of the nasty selfishness of each family living in its own little den, like hostile animals, the whole building is now open to us all. We go where we like. Only last night three of the comrades sat in my room beside my bed after I had retired and sang Russian songs by the hour. Under the old, selfish regime I should have slept—as it was, I didn't.

If a comrade wants food,-he takes it. Three nights ago I woke up and saw a comrade with a dark lantern looking into my ice-box. "What is it, brother?" I asked mildly. "Cold ham, comrade," he answered. "Hast thou any?" "Take, and take gladly," I said. As a matter of fact, I had eaten all the ham before he came up; but it illustrates the principle of the thing.

The Common Pool

WE admit that the organization of our little soviet is as yet incomplete. In beginning a soviet the real true way is that the members shall all be united in a common and harmonious occupation. Then the common product belongs to all. It says this in our handbook. By fights our soviet ought to take over a whole industry, or at least a self-determining part of one. This is difficult for us. We have not yet decided among ourselves on what would be the most harmonious occupation for us. Some of us think of playing the mandolin; others, fishing; there is no general agreement.

So, instead of beginning in a complete way we have sovietized all our wages. Comrade Globenski explained to us how to begin that way, and it seems so simple that any little group of people can start like that, while waiting for the higher form of the soviet to evolute itself. Globenski says that he could start that way with even only one other person. How wages are sovietized is like this: We all bring what we earn to Globenski, and then it becomes a pool and belongs to all of the brothers and sisters in common. Every Saturday night each brother brings what he earns and lays it down on a little table in front of Globenski and says: "Take this, little father," and Comrade Globenski says: "I do take it, little brother," and he does.

One week, one of the comrades accidentally kept back half of what he had and he was accidentally gas-piped the same evening. The coincidence struck everybody at once.

If any comrade is without work and without pay, it makes no difference. He simply says to Globenski: "Oh, comrade, I have nothing." And Globenski says: "And what of that, oh, brother? Have we not what belongs to us all? Take and take freely." The thing is so beautiful that it makes one lose his taste for capitalistic society altogether. A lot of the brothers have lost it so much that they have been compelled to stop work.

When a brother feels that he can work no longer in bourgeoise society, all that he has to do, is to go before Globenski and hold up his two hands and say: "Look brother, I work no longer!" And Globenski says: "I notice that you don't."

Everything has to be said or done with little formulas like that. We get them out of the Comrade's Handbook. Of course, to get the full good out of it, we ought to be able to read it in Russian. But we can't quite manage it yet. We are working away on it, however, in the evenings, and are away on in the alphabet already. 1 wo of the comrades passed the sixteenth letter neck and neck last week and are still forging ahead. And Globenski is teaching us little phrases orally, such as "Have I the property of my brother," "No, but I mighty soon mean to."

But at present we still read the Handbook in English. It's not so strong that way, but it's strong enough.

The Children Question

THERE are no doubt points about our soviet which may need perhaps a little reconsideration. One, for example, is the question of the children. We all felt at the outset that we wanted to adopt the full soviet idea regarding children as common property, a blessing shared by all the comrades. But in operation it has made difficulties. To take a case in point. A week ago I took all the little Rubensteins to Coney Island, it being my day to be out-of-door guardian of the common blessings—that is to do what used to be called minding the children. When I got back, one of the children — at least, so Mr. and Mrs. Rubenstein claimed—was missing. I admit that I had not counted them very carefully at the outset and was not exactly certain whether there were six of them or seven. But the point is that I don't think Mrs. Rubenstein ought to have taken the ground she did. As I reminded Rubenstein, the loss, if there was one, was just as much mine as his. I had lost my share in little Willie Rubenstein just as much as he had, and it seemed to me that the only way was to put a good face upon the matter and to write Willie off as a loss and to start over again. There are a good many comrades who thought as I did, and there was a good deal of feeling in the matter. In fact, it was about that time that we began considering sending the Rubensteins as delegates to Russia.

(Continued on page 106)

(Continued from page 58)

There have been little difficulties, too, about our amusements. Many of the brothers are fond of playing cards and, especially when the brothers have desisted from outside bourgeois work, they like to sit in the soviet and drink 2 per cent Kwas and play Skoot, which is a Russian game something like the one called poker. Two of the brothers were playing Skoot the other night on a soap box by candlelight, and I stood watching the game, and when it was all finished, one looked up and said to me: "Sorrow with me, O brother, I have lost your Sunday overcoat." And the other: "And with me, too, little brother, I have lost your patent leather slippers. Share my grief with me till it heals."

I felt a little bit puzzled by this. Some of the brothers think we ought to have a little less Skoot about the soviet—others think we ought to have more.

Little difficulties like these have made some of the brothers and sisters think (especially those who are still working) that perhaps our organization was premature. Possibly we ought to have developed a higher common moral synthesis—I am quoting the Handbook— than whatwe had. Personally, I have been feeling that the one I had was all used up. We are thinking therefore of selling our soviet to anybody who would like to buy one. There is so much talk in the newspapers now and in ordinary conversation about the advantages of the soviet that we are certain lots of people would like to buy one as a going concern. If so, they can have ours. They only need address us at "The Soviet Apartments, Group One, Division One, of the Soviet Brotherhoods of the World," with enclosed stamps for the answer.

In fact, as soon as Globenski comes back we shall sell out. He had to leave us two days ago so as to carry our money—he had it in a little black bag— to a safer place. He said he was not sure of it. He said that he knew a man who would look after it, a comrade whose word was sacred and whose heart, so Globenski said, was love itself. Globenski doesn't seem to have found him yet and is not back. Some of the brothers are a little troubled. They fear that perhaps Globenski has been seized by the agents of the Counter Revolutionary Party. He himself told us that if he ever disappeared, that would be where he'd be.

Meantime our Little Soviet is for sale.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now