Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAt the Sign of the Blue Lantern

I. The Little Flowers of Frances

THOMAS BURKE

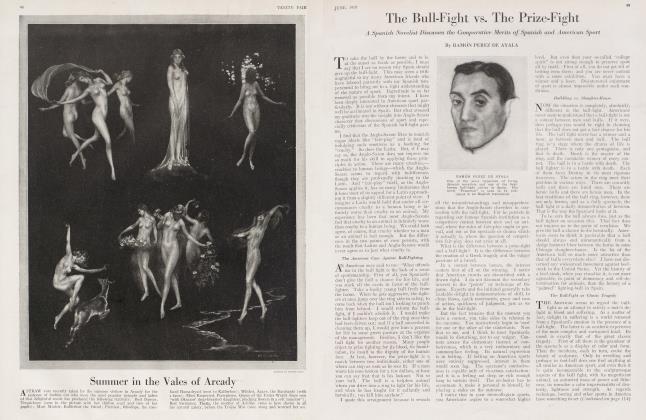

THEY'RE a sorry crowd, the reg'lars of The Blue Lantern. Even the brightest of them, the flash boys and girls, carry their terribly new store clothes with a bedraggled air. The others are nakedly downcast, without clothing or bravado to cover them or weapon of spirit to arm them. Yet, though all else perish here, beauty and love and sacrifice survive. In these waste places about the Pool of London, whence men, in sweeter quarters, gather fortunes, craft and greed and unnameable iniquities propagate and flourish, and curl their soiling arms about all that is brave and sweet. Yet beauty persists; even in the heart of darkness love takes root and spreads therein its eternalenchantments of gardens and moonrise, of glory and humility and peace.

The Blue Lantern stands on Chinatown corner, where the missionaries love to prowl. It is kept by an ex-bruiser known to his reg'lars as Dickery Dock. It is to Limehouse what the village green is to the rural community. It is the centre of past history and of current effort. In its bars new friendships are formed, and old scores bloodily wiped out. There, hot, hard wordsf and vociferous debate lead to blows and the police-court, or end, more ignobly, with shocking beer-shed.

There, valorous schemes are laid, and the vain cunning of the police is with sharper cunning frustrated. There the keen wit of the Cockney meets the deceptive frankness of the Oriental and the tortuous reserve of the black, and is often bested.

Upon an evening of winter, when, in the river-mist, the substance of the streets melted into shadow, and shadow took on body, Dickery Dock looked about the house and stroked his chin with complacent gesture. At the same moment a policeman, trying to look like an ordinary citizen, looked in, and also made a complacent gesture. All the boys were therevigilance could be relaxed for a while. Dick the Duke was there, with his usual crowd of worshipping ladies. There, too, were Binkie Flanagan, the automatic-machine expert, Nobby the Nark, Big Bessie, some of the Roseleaf Boys, old Quong Lee and John Sway Too, little Chrissie Rainbow, and, in a comer, Singa-song Joe, the looney. All the reg'lars, in short, replenishing from pewter pot and uncouth glass their store of hope and enterprise, and recovering that calm acceptance of the untoward which men call philosophy. As the rattle of coins on the counter increased, so did the buzz and clatter of the saloon and fourale bars gather volume. Listening from without, the stranger would have said that everybody within was happy. Their noise flowed to the street like the quiet gurgle of a self-satisfied stream: a stream that ignores in its careless passage the muddy bed over which it flows.

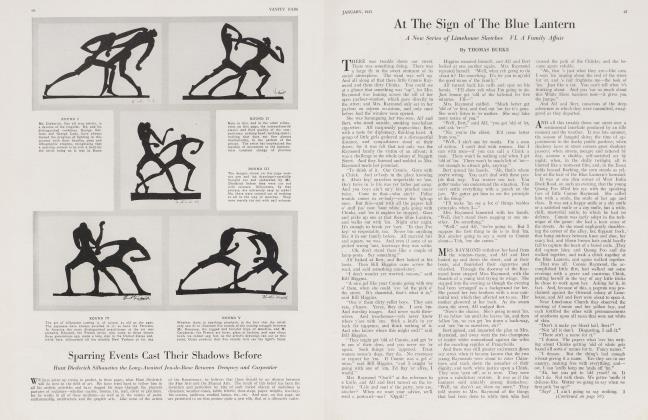

BUT one among the reg'lars was not happy; could not even borrow an hour's delight on the usury of the glass. Frances of The Causeway, described colloquially as "Fanny, poor kid," sat alone on a bench, face and hands listless. Although sitting with the crowd, she had dropped the mask of alert nonchalance assumed by girls of her class in public places. The strain of carrying it was too intense for her worn nerves. In the last two days she had realized that she was a back number. Such beauty as she had once had was now obliterated. Her hair was thin and colourless. Her face no longer took aptly the emolients and powders that she applied. It was becoming an effort to be skittish and effervescent in the presence of potential customers. She was no longer facile in dalliance; her profane comment no longer came pat to the occasion. Even the black men about the streets failed to look twice at her.

She sat "all-gone," as she would have expressed it. The bright light of invitation that customarily sat on her face, once assumed as a trade trick, later to become habitual, was out, and the coarse face hung empty. But in every line of the flagging figure was written disgust and yearning. She was done, and she knew it; and she held yet enough of her first girlhood's love of the good and the seemly to suffer disgust at her situation and impotent desire to amend it.

OTHERS had played her game, and had done well out of it. Some had married Chinks, and now led silken lives, with flowered temples made to their honour. Others had moved up West, where they had found sleek protectors and had put money in the bank. Others had married seamen or small tradesmen. All had been careful where she had been gay, spending money as she got it and financing men friends when they were hard up. Little Chrissie would not be that sort of fool. She was in the game for solid reward, and saw that she got every promised penny out of it. Greenstockings, too, knew where to draw the line between frivolity in business hours and recklessness in leisure. But Fanny had been caught by the festal side of the life and the loud company, and had crowded a jag into every hour.

And now she was through, and they talked of her. "Whassup with Fanny, poor kid?" asked Greenstockings. "Looks as though she'd drawn the winner and lorst the brief."

"I dunno. Seems to 'ave got the fantods lately. No doing nothing with 'er. She can't get the boys now, and when she told me she was 'ard up, and I told 'er she ought to go to the Mission Workers, and they'd get 'er an honest job, she fair snapped my 'ead orf. Fact is, she's made a mess of things. She didn't ought never to 'ave bin in this game. She ain't fit for it. She's too—you know—too— thinks too much, like. She's told me. Although she's done things I'd never do, she ain't comfortable. Keeps on thinking of what she's done. She ought to 'ave bin respectable, reely. She's made for that. Can't you see 'er bathing the baby and getting 'er old man's dinner? She ain't cut out for this. She's let it get 'old of 'er too much."

Fanny sat brooding. A young seaman, in neat, shore-going clothes, bought a drink from the counter, and sat down near her. He glanced at her; then edged away. She caught the glance and returned it, not professionally, but with appeal. She leaned towards him. "Lend us 'alf-a-crown, boy."

He looked up again; edged a little further away; then turned a shoulder and bent to his glass, awkwardly, as one afraid of such women while afraid of not behaving like a man of the world. "Lend us a shilling, then."

He became confused; remembered an appointment; drank up and departed.

Dickery Dock, seeing that she was without a drink, called to her: " 'Ave a drink, Fanny?"

She went over to the bar. "No, thanks; I don't want a drink. I say, lend us half-acrown, Dicker)."

"Lend you 'alf-a-crown? 'Ere—come orf it. This ain't a Finance and Mortgage Corporation. You can 'ave a drink on the 'ouse, if yeh like, but-"

"No, I want money."

"Money? Well, I don't know what yer chances are of gettin' money 'ere. Where's yer security? Where are you going to get money— now? You ain't got nothing to sell now, Fanny. You realize that yesself, doncher? You're past it. No, Fan, you ain't got no chance with the boys about 'ere against little Cherry and young Greenstockings and the other flappers. No, kid, you'll alwis be welcome to a drink 'ere, but money's another matter. You know I make it a rule never to lend money. I don't mind sticking up a drink when a chap's 'ard up, but lend 'em money to spend in other 'ouses—no."

"I don't want it to spend in other 'ouses."

"Wodyeh want it for, then?"

"I want to go somewhere to-night."

"Want to go somewhere? Well, that's fairly brassy. Want to borrow money to go away with? If that ain't the bally limit! You take the 'Untley & Palmer, you do. No, Fan, I'm sorry, but I 'ardly think that security would be good enough even for Mugg from Mugtown. 'Ave a drink."

"No, thanks. I'll go. Where I won't bother nobody."

SHE turned from the bar, her face momentarily expressing chagrin, until its lines deepened into utter misery. The landlord looked after her, puzzled at her attempt to break his rules, and at her attitude. As she crept through the swing doors, he looked at some of the boys standing at the bar. " 'Ear what she said? I think she wants watching. 'Where I won't bother nobody,' she said. See if you can find old Nobby, and get 'im to keep an eye on 'er. She looks as if she'd got something in 'er 'ead—making a 'ole in the water, or some idea of that sort. She better be looked after. We don't want another scandal round this 'ouse, just on top o' the last."

They dug out Nobby, and despatched him on his errand; and the beer engines banged and hissed, and the cash register clattered and rang, and the turmoil of glass and voice rose with the rising hands of the clock.

At half-past nine Nobby returned. He sat down on the lounge, and his shoulders and stomach vibrated and bass rumbles came from him: Nobby was laughing. He always laughed privately, within himself; but in the communism of the public-house private laughter is frowned upon. There men abide by the Christmas-card maxim that the weary old earth is in need of your mirth, it has grief enough of its own.

(Continued on page 116)

(Continued from page 71)

"Now come on, tell us the joke. Spit it out. Don't keep it all to yesself."

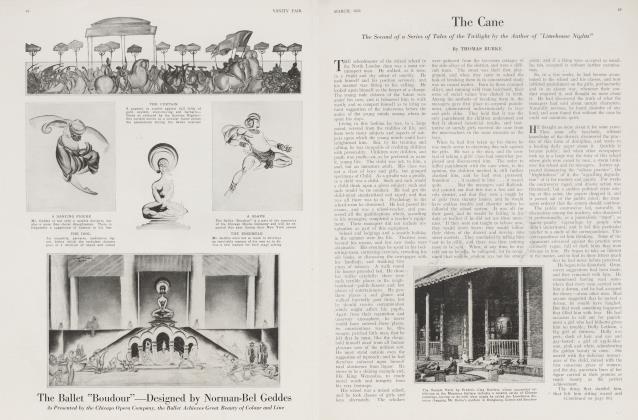

"G-get us a d-drink, someone. Bitter. I was laughing," he jerked from tremulous lips, "I was laughing at Fanny, poor kid. She's just bin nabbed."

"Nabbed?" snapped Dickery Dock. "Whaffor? 'Tempted suicide?"

"No. Pinching—p-pinching f-flowers!"

"Pinching flowers? Shurrup!"

"True's I sit 'ere. Pinching a fourpenny bunch o' lilies-o'-the-valley from old Gorton's shop, an' old Gorton caught 'er at it, an' 'anded 'er over."

"Well, it sounds queer, but I don't see nothing to laugh so much about."

" 'Tain't the pinching—though that's funny. It's what she said when they arst 'er why she done it. Wod yeh think she said? Our Fanny, mindyeh. Frances of the Causeway—knowing 'er and 'er ways as we do. Wod yeh think she said?"

"Go on. What?"

"Said she pinched 'em 'cos she 'adn't got no money and wanted 'em bad. Said she was fed up with things and was going to end it, and wanted the flowers 'cos a bad girl like 'er couldn't go before God with nothing in 'er 'ands. Fanny, mind yeh! Talk about laugh!"

He leaned back and chuckled again, and some of the men with him, but the girls did not laugh.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now