Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowParisian Nights and French Music Halls

ARTHUR SYMONS

Polaire: The Folies-Bergère: Señorita Santelomo

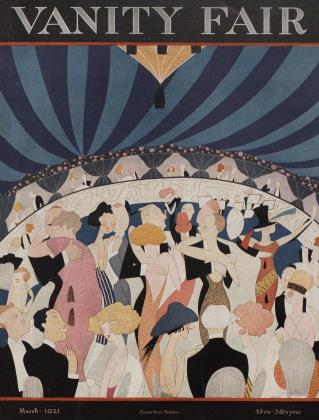

THE Theatre de la Porte Saint-Martin, on the Boulevard Saint-Martin, has been giving this year an extraordinary drama called Montmarte, by Pierre Froudiere. The plot is simple and amusing, ironical and decadent, and Parisian. Marie-Claire,—Polaire acts her—is one of the street-girls who used to haunt the Moulin-Rouge, who meets there Pierre Marechal, a young musician; they take the usual fancy to one another, she becomes his mistress; he, of course, belongs to the Quartier Latin. She finally gets bored; his atmosphere is not hers; she has none of his seriousness; she rebels and has a nostalgia for the rue Lepic, which leads to the Moulin de la Galette. One night, one of their friends—a composer— turns up, assures Pierre Marechal that his opera has had an immense success, and wants to take both of them to the Moulin-Rouge. Pierre refuses; she, hysterical, leaves him. This closes the first act.

In the second act she is the companion of a rich man namel Logera and, in an exciting scene, Pierre, her lover, returns to her. As her old passion for him conquers her, they escape from Logera. In the third act she is violently seized by the spell of Montmarte and the Moulin-Rouge.

The Terrible Polaire

POLAIRE, for whom the play was made, seemed to me magnificent, in spite of her age—one never knows the actual age of any actress—and, in fact, extraordinary, malicious, pernicious. Her face is more horrible than ever; the face of an absolute Vampire, of a Vampire with a writhing whirlwind of rebellious hair, that crawls across her forehead and over her ears. Her eyes are wicked—abnormally wicked, with a hard and perverse glitter in their fixed gaze; they roll from side to side, always in some uncontrollable fashion; are always restless, always nervous. Yet, what is so wonderful is, that in one scene she is so swept away by the torrent of her own emotion that the tears literally stream down her cheeks. Her nose is ugly; there are heavy and deep wrinkles that curve upward from the lips to the nose. Her mouth is large, her lips thin, her chin oval. If the Devil entered into any human being—as he has a fashion of doing when he chooses to—he certainly at one period haunted Polaire.

Utterly animal, she has a certain command over her nerves; that is, when she is not all nerves. Agile as ever, she retains her gaminerie. She can run, leap, jump—do anything; be natural and unnatural, normal and abnormal, serious and cruel, sardonic and malignant. She is still in possession of her genius; not that she is a great artist, like Sarah or Rejane; but the fact is she can, at times, all but achieve greatness.

All gesture, vivacity, curiosity; feverish and morbid; over-excited, capable of caresses but not of passion; incapable of loving, she lets herself go. And, when her hysteria carries her beyond the bounds of her power of resistance, she is absolutely amazing: a creature, as it were, torn asunder by two unequal attractions: the wild life of the Moulin-Rouge and the life she finds it impossible to endure in her lover's company. Like Io, stung by a gadfly, as one poisoned, she rushes to and fro, crying incoherent words.

That Polaire has studied Rejane is certain; only in Rejane's genius there was a kind of finesse: it was a flavour, and all the ingredients of the dish may be named without defining it. The thing is Parisian, but that is only to say that it unites nervous fire with a wicked ease and a mastery of charm. Polaire, on the night when I saw her, gave me several thrills: not the shudder in the spine Yvette gave me; nor the intoxication of Rejane's appeal to my senses. I could cruelly enjoy Rejane, but not Polaire. Polaire never gives me the effect Rejane did, in a scene where she repulses her lover, and with a convulsive movement of the body, lets herself sink to the ground at his feet. Only, in regard to passion, where Rejane was supreme and consummate, Polaire is neither consummate nor supreme.

The Folies-Bergere in Paris always has been, on the whole, an unsuccessful attempt to imitate an English music-hall.

The Folies-Bergeres

I WENT a short while ago, several times to the Folies-Bergeres. The show, L'Amour en Folie, Revue a grand spectacle en deux actes et trente tableaux, by Louis Lemarchand, was on the whole, curious. It began, as usual, stupidly, but with the invariable rattling and sonorous and exciting music, of the Orchestra, this time to the music of M. Gavel. It amazed me to remember an extraordinary spectacle I saw at this music hall, a pantomime by Catulle Mendes, which was called 'Chand d'Habits. It was a piece of fantastic horror which recalls one of the Tales of Hoffmann, and it was acted by Severin with an astonishing force and expressiveness. Pierrot, in order to gain riches, has killed and robbed an old-clothes man ("Marchand d'habits") who is a miser. The image of the man he has slain returns to him just as he is about to set to his lips the cup of every wine of the felicity of earth. The body of the woman he loves turns before his eyes into the body of the man he has murdered; transfixed by the fatal sword, it rises out of the earth, finally, to claim him. Then comes the really terrible, the really admirable, piece of acting. Pierrot tries to escape, but before he can reach the door he is drawn back by the force of his own terror, the intolerable magnetism of his own crime, to the feet of the avenging phantom. He implores, entreats, breaks away, returns, breaks away again, mocks at his terror, and is seized, imperceptibly, inevitably, by the fascination of the transfixing sword which points unwaveringly towards him, those open arms which wait to embrace him into death. It is with the very ecstasy of despair that he flings himself at last into that embrace, and goes down suddenly into hell, the victim of his victim.

L'Amour en Folie was followed by Un souper a l'Abbaye de Thélème. This was made amusing by a splendid pilgrim monk who really made one laugh by his outrageous manners, his surprise at finding himself there, his refrain, a frightening one: "Il faut mourir!" Then followed J.es yeux du Cirque, an arena in the reign of Nero, who is seen gazing on the tortured figure, with Messalina beside him.

La Danse a Biskra, which followed, was done in a more or less Oriental fashion: the Harem, slave-girls, Eastern music, slow dances. Only, when La Belle Baia entered, I saw in her what I had seen in Sofia and in Constantinople. She was wonderful, supple as a reed, subtle as a snake, with those strange movements so characteristic of her race. She danced and mimed; made her invariable undulations and convulsions of one part of her body after another; all with an Asiatic grace. Then her dance becomes wilder, as the man slave dances with her. They turn round and round together with a strange and troubling rhythm.

La Maison de Danse a Seville gave me— after having lived in Spain—no more than the vague aspect of an imaginary posada. Senorita Ritier sang, with a certain expressiveness, one of Raquel Meller's songs. I waited in intense excitement for the entrance of Senorita Santelomo. As she entered, swaying in the Spanish fashion, some of the dancers I had known in Spain returned to me in memory. Santelomo is young, wonderful, amazing, perfect in her art. She comes in, dressed in a black Spanish dress with a huge amount of flounces that fitted her tightly; there was a long black train behind, lower in front, that when she moved showed her laced white stockings and tiny feet. There danced before me—and, alas, to an unenthusiastic audience—an absolute Goya, with dead black hair, a malicious smile, a delicious face—"a face made wonderful with night and day", but essentially Spanish —a comb, and a rose in her hair. She danced to the sound of her orchestra a Malaquena, with those snake-like undulations of her lithe body and Spanish waist and hips. Graceful and passionate, she exulted in her dancing, as I did—with that nervous clash of the castanets.

(Continued on page 88)

(Continued from page 43)

In her next dance she wore a man's level black bat: she was dressed in white with one of her mantillas. Campiello—so Spanish, so much in his element even in Paris—strums his guitar. She stands motionless, gives one a sense of suspense, twitches her lips, then stamps three times, clashes the castanets, turns slowly—slowly, bends her body to a soft rhythm. Then she rises, turns, stamps her feet thrice; then waits, again in suspense, as the guitar sounds faintly, with castanets in her raised hands; after the pause, she makes the castanets sound like little broken sighs or sobs—a woman's in anguish— one just hears them; then the sound increases—she turns more rapidly: stamps again with more violence. Then she begins to crawl across the stage, insidious as some sweet and secret poison; then comes the same quietude of body, the slight clashing of the castanets. Then the music grows louder; she writhes in a narrower and narrower circle, as if imprisoned in her tightly clinging dress; with one nervous heel she kicks back her long train. "So," said I to myself, "do they dance in Spain."

She is a great artist; pure and passionate, perfect and perverse; she has genius and youth and fire and fascination. Imagine a wild beast full of infinite cunning—and she is that; imagine such beasts as shameless—and she is naturally that also. She creates before me in so small a space of time a form of dancing I have seen over and over in Spain—as in the dances of Josefer Dicz, the gypsy dancing-girl in Malaga, as in the dances of the finest Spanish dancers. This girl, like some of these, is elemental, primitive, instinctive; she has a natural gift; she is all fine nerves and concentration, calculation and impulse. Conscious as she was bound to be of her exquisite beauty and of her supreme art, she really seemed to like her public. I noticed that, in her last dance, as she grew more excited and turned on herself before the final pause and last clash of the castanets, she cried: "Hold.I Hold!" She cried these words in her guttural voice as her long earrings quivered and her adorable face glowed like a pallid rose with faint touches of colour.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now