Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNew Theatres for Old

The Modern Effort to Provide a Fitting and Decorative Setting for the New Dramatic Ideas

KENNETH MACGOWAN

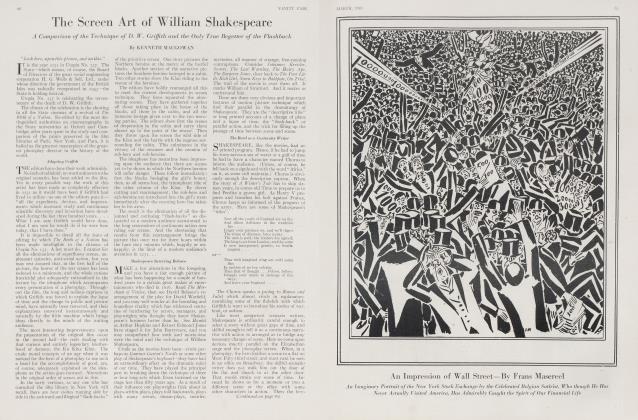

WE have heard an unconscionable lot of talk about the "new theatre". Where is the thing itself? We have had plenty of new scenery, some new acting, and once in a while a faint indication of a new play. But no playhouse that is literally new—new in shape, design, decoration, function. All the elements in the movement toward a new theatre which we have so far developed are almost invariably exhibited in what is fundamentally a nineteenth century playhouse. We go into the peep-show of Ibsen, and stare diligently through the fourth wall, just as we have been doing for two generations, and at what? At something which is as new and different from the product of the Ibsen tradition as the Ibsen tradition and the Ibsen theatre were different from the Elizabethan or the Elizabethan from the Greek. Ours is a thing just as much in need of a new and different theatre.

This problem of the new theatre has presented itself to a few of the producers, to Copeau and Reinhardt and Dalcroze. These men and certain stage artists have sensed in varying degrees that the age is ready for a really new playhouse. They have seen the absurdity of putting plastic, imaginative, abstract scenery into a box where people expect to find something else. They have realized that the new dramatic idea—keener, freer emotions, playing through simple, fresher and more unconscious mediums—calls for a new stage on which players and colours may move in fresh ways, upon different levels and from different angles. And they have realized that the audience which is going to understand this departure from the old form of realistic-make-believe production must find a change in the very auditorium to give them a sense that something fresh and different is going to be shown them. The old auditorium and the old pictureframe proscenium are inadequate. They cannot handle the new movement of the players, and they fail to lead the mind of the spectator into new channels.

The American Artist in the Theatre

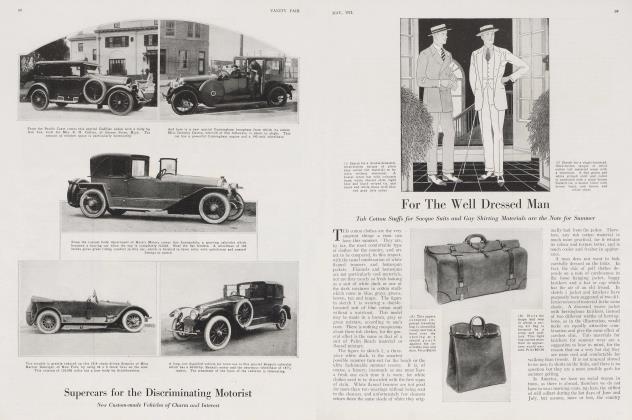

EUROPEAN producers have worked for a solution of this difficulty, now in this place and now in that. Littmann has designed moveable fore-stages, and auditoriumslikethe Munich Art Theatre withspecial side entrances outside the proscenium opening. Max Reinhardt in his "theatre of the five thousand", the Grosses Schauspielhaus, has cleared out the orchestra floor for his actors to play upon, and has fashioned a stage like none to be seen anywhere else in the world.

The first American step in breaking down the old theatre came when Joseph Urban introduced "portals", or new proscenium openings within the old ones, supplied with doors, and permanently unified with the different stage settings behind and between them. Like the "flowery way" of Sumurun, which led the actors down from the back of the auditorium, over the heads of the spectators and across the footlights to the stage itself, the "portals" have since been largely confined to musical productions. Jones and Geddes have dreamed of new theatres and adaptations of old ones, in which all the paraphernalia of scenery, back drops and prosceniums should give way to symbolic backgrounds, variously raised levels for the actors to play upon, a new physical approach to the whole business of moving people about before an audience.

Now a new artist comes to Broadway with extraordinary and daring sketches of how our "new theatre" may actually look when we have tried to escape from the old "peep-show" to a playhouse of fresh quality. He is Hermann

Rosse, born in Holland, trained i'n Holland, England and Italy, and for ten years more or less resident in the United States.

In Holland he has painted the murals and decorated the interior generally of the Peace Palace at The Hague, and the new Rotterdam City Hall. In San Francisco, in 1915, he supervised the decoration of the Netherlands Building of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. At various places in the West he has decorated such very different things as an automobile show, a Christmas Nativity Drama, musical comedy, drama and opera. New York saw his work first last winter in Madame Chrysahtheme, the Messager opera of Japan, mounted by the Chicago Opera Company. Last summer in Holland, he made designs for a theatre for Herman Heijermanns, the Dutch playwright and producer, and sketches for the settings of Roland Holst's Thomas Moore, which is to be one of Heijermann's first productions in his unusual playhouse. Within the past month Rosse has had a one-man show in New York in which his designs for new playhouses, as well as projects for new methods of production, have been exhibited. In the course of the past ten years Rosse has varied his life as a creative artist with expeditions to the East, to Japan, China, Dutch Java, and Bali, and has been the head of the Department of Design of the Chicago Art Institute.

The Architecture of the Playhouse

ISHALL say littlehere of the individual character of his drawings, or the unusual technical methods through which he expresses himself, his utilization of batik means, for instance, in making his sketches. The dominating thing that I find in his work and his personality is his emphasis on a new way of looking at the physical theatre.

The first approach is architectural. Rosse has spent much time and energy on schemes for uniting the lines of the proscenium opening of a theatre with the lines of the house, for bringing a real artistic unity into the architecture of the auditorium. You will see how easily he accomplishes this in the sketches reproduced with this article.

But all that is a small element in his work. He has gone beyond this to the designing of stages with new and beautiful approaches— doors set in the proscenium itself; "flowery ways", leading along the sides of the auditorium till they merge with a stage flung out in graceful curves beyond the confines of our footlights; steps down from the stage to the floor of the auditorium; the stage itself divided in ingenious ways by walls, pillars or screens of patterned colour to make a background for the play. Beyond these purely static decorations, Rosse now seeks a dynamic background.

Going beyond the physical theatre, again, Rosse has begun to scheme scenic backgrounds in which there shall be as much life and as much drama as in the actors themselves. He has planned to place within the prosceniums of his new theatres, upon drops, curtains or gauzes, an illusion of moving scenery, partly accomplished through varying lights and moving materials, and partly through designs projected on these surfaces by the motion picture machine. Through thousands .of drawings—made and photographed much after the manner of the animated cartoons of the movies—he would create an absolutely living and dynamic background. This background would necessarily out-act the actors, but such a method of production is intended only for an entertainment in which story, action, colour, music, pantomime and voice would be fused to create a new type of continuous emotional spectacle.

(Continued on page 84)

(Continued from page 57)

This is such work as the Russian Ballet has given us, pushed to the last degree of completion. The Diaghileff Ballet, Rosse points out, has added to the motion of the actors and the rhythm of the music a motionless representation, on the backdrop, of the vivid dynamic emotion of the ballet. There has always been something of a conflict between the moving, living occupants of the stage and the static background. Rosse proposes to bring the scenery to life.

The Triumph of the Decorative

PUSHED to the last degree, this means the elimination of the actor as the primary factor in the theatre. This is the accusation made against the newer designers in all their work. Rosse accepts it frankly in the case of the particular variety of vivid and emotional entertainment which has most readily utilized these artists' talents. He thus writes of the product: "From a purely æsthetic viewpoint the effect of this developing of the background at the expense of the actor will remake the dynamic play. Imagine beyond the proscenium a void in which planes and bodies will develop themselves in limitless graduations of color and shape in one great rhythm with the coordinating music—two-dimentional patterns in kaleidoscopic succession, and these fascinating patterns formed by the intersection of solids, darts of color across a sombre background, lines, planes, or solids, and symbols of man and surrounding nature, all emphasizing the mood of the music!"

Frankly, this is the triumph of the artificial, the decorative and the stylistic in the theatre. It is the tendency toward a purely pictorial theatre pushed to such limits as almost to become a glorified and enlarged and immensely beautified companion of the motion picture.

But this is not all that the "new theatre" means to Rosse. We must have a theatre for the imaginative and humanistic drama ,of words,. the drama that reaches back to the Greeks and forward to new types of plays whose emphasis is upon life and its philosophic and emotional meaning, rather than upon mere beauty and excitement. It is this theatre that seems ultimate, and this theatre that Rosse* has again and again attempted to design in sketches such as the one reproduced at the bottom of the page. This is intended for a dance, but the principle of a permanent architectural setting with a small portion varying, as with the Greeks, applies broadly.

"There are now plays", says Rosse, "and it is safe to predict that there will be more soon, for which the pure structural beauty of an unadorned building will be sufficient; such will in fact be the only entirely right method of mounting them. Nearly all the plays of a meditative, analytic nature, all plays of words, could thus be acted on a beautifully finished platform."

The Return of Realism

IT is ultimately to this type of play and of theatre that Rosse gives allegiance, although the unguessed opportunities of novel and picturesque play of moving scenery have stimulated him to much immediate effort. The actorless stage will decline almost as soon as it is accomplished. The other stage will live forever.

"That which will always conquer art," says Rosse, "is reality, life itself. In the theatre of to-day two tendencies are very evident—one toward a rare and precious artificiality, and one toward a new and vital realism. The first tendency will probably work itself out in the actorless theatre. The second tendency will probably lead by the way of a slow development of the purely constructive stage and the oratory platform to a new type of churchlike theatre, with reflecting domes, beautiful materials, beautiful people—to a revitalizing of art by a complete reversal from the artificial to the living real. If we are going to stay true to the spirit of the time, both of these tendencies will develop side by side until reality carries the day."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now