Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBambino the Maestro

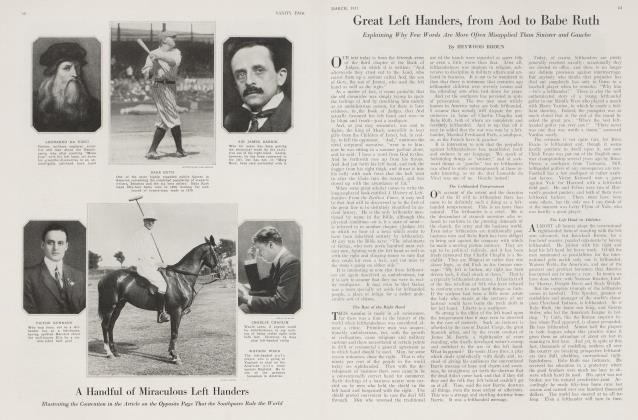

The Suggestion of a Possible Freudian Interpretation of the Aesthetic Appeal of Babe Ruth

HEYWOOD BROUN

THE beginning of another baseball season marks the growing development in America of appreciation for the aesthetic. We used to boast that the game was a science. Now we know that it is an art revolving around one great master. Need we name Babe Ruth. The revolution has been effected within the space of ten years. A decade ago all rooters thrilled to the revelations of Hugh Fullerton concerning inside baseball. He declared that a championship team was as well ordered in its action as a superb piece of machinery. The individuality of every player was merged into a fighting unit. Baseball was recognized then as another manifestation of American genius for organization. The same sort of intelligence which formed the Standard Oil Company went into the moulding of the Chicago Cubs.

It was admirable but it was not art. The magnificence of the achievement was wholly material. Once again the individual was merged with his fellows for the common good. Of course symphony orchestras are something like that and community masques, but, generally speaking, the artist is the fellow who catapults out of the scrimmage and proceeds down the field alone. The only cooperation he requires is the temporary use of a few faces to walk upon.

Baseball has been saved for art by Ruth. By means of his fifty-six-ounce bat he has hammered the game entirely out of its slick shininess of mechanical perfection and science into an adventurous something which undulates continually between the sublime and the ridiculous. He has made it a field of endeavour in which man is alternately riding with the clouds or lying flat on his face in the mud. Poetry, painting, and sculpture are just like that.

Greater than Baseball

RUTH is essentially an artist in that he gambles with his dignity, ready at any moment to fail utterly and miserably if only now and again he can knock the ball over the fence. Judge Landis asked plaintively at the close of the last season whether Ruth was greater than baseball. Queen Elizabeth might just as pertinently have inquired whether Shakespeare was greater than drama. The answer is, "Of course." Any true artist must transcend his medium. For the moment Babe Ruth is baseball.

The spectator much given to watching trained elephants has probably observed the formula which universally marks their entrance upon the stage. First comes the biggest one and behind him the next in size and so on and each elephant holds firmly to the tail of the fellow in front of him. Such is the progress of art. Babe Ruth governs the entire direction of the game. He has made the home run the aim and end of baseball although once it was merely an exciting incidental. Teams no longer try to help a man around the bases bit by bit, but endeavour instead to blow him home with one mighty gust of offensive strength.

It would be unfair to intimate that everybody is satisfied with the existing condition of baseball. There remains a considerable school of precise people who regret the introduction of the inspirational quality. This group seems to us more articulate than numerous. Last season they managed to convince some of the ruling powers that the great paying public was out of sympathy with the terrific hitting which prevailed during the season and desired a return to the days of the low score game and the pitchers' battle.

It seems to us that such a claim is wholly unfounded. There was nothing in the behaviour of crowds at the Polo Grounds last season to give support to the contention. Even better than evidence is well considered theory and in the field of speculation the arguments of the low score game necessarily go glimmering. Even the most casual Freudian must realize that the average rooter is subconsciously against the pitcher. This player must inevitably stand as the symbol of repression. He is the guardian of things as they are. Given two perfect pitchers every game would go into darkness and a tie score at nothing to nothing. In other words the condition obtaining at the beginning of each contest would be continued indefinitely. Now a rooter goes to a baseball game just as a spectator goes to a play because he is not wholly satisfied with life. He wants a change from the routine of existence which all too often can best be expressed in the formula of 0 to 0.

The batter is the man who attempts to mould life a little nearer to the heart's desire. The formulae within his potential power are innumerable. Thus he stands as the symbol of the human will desiring something which it has not chiefly because it will be different and perhaps better. But first he must conquer the opposing pitcher, chief factor in the forces ot frustration. We hope it will not be considered extravagant if we suggest that the subconscious spectator tends to identify the pitcher with all the forces of negation throughout the world. As he winds up and puts upon the ball every ounce of repression which is in him, he becomes suddenly a little brother to Puritanism, Volstead, law and order, the family and the home, the Malthusian theory, and keep off the grass. As the ball sings through the air the message which it carries is, "You cannot." And against this tyrant there has risen a champion of the hopes of humanity. Babe Ruth's bat also has a singing swish and it cries out, "But I can." And when ball and bat meet, the ball changes its tunes for as it scars screaming over the fence even the dullest ear can hear it exclaim, "Blamed if he didn't."

The Complete Enthusiasm

CERTAINLY nobody can deny the obvious symbolism of a fence. We do not refer, of course, to the signs "Traprock Tires," or "Have You A Little Weaver In Your Home." We mean that in any dream a fence must stand for something which has been reared up against an individual to limit his aspirations. Consider then how deep seated is the thrill when Ruth puts new hope in every heart by showing that fences are no more than low hurdles for the man who dares to will and refrains from biting at the bad ones. This feeling is so universal that even the partisanship of local pride cannot stand against it. Reporters noted many times last season that hostile crowds cheered Babe Ruth and hissed home town pitchers who forced him to accept a pass instead of giving him an opportunity to hit the ball.

It must be admitted that crowds also laugh and cheer when Ruth strikes out, but that does not fall outside a psychoanalytical explanation. This reaction is largely defensive. Mankind is accustomed to failing and so it likes to pretend that there is something amusing in it. The crowd which roars with laughter when Ruth swings for the third time and falls on his face is merely seeking to conceal the fact that its heart is breaking.

A few may object that the aesthetic appeal of Babe Ruth is lessened by the fact that he receives a great deal of money for his efforts. Nothing could be more materialistic than such reasoning. By happy circumstances Ruth's mind has been relieved of all financial worries. Other players are distracted occasionally by fretting about gasoline or tires, but Babe can devote his entire attention to baseball.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now