Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNotes on Painting and Sculpture

Comments on the Current Exhibitions in New York

PEYTON BOSWELL

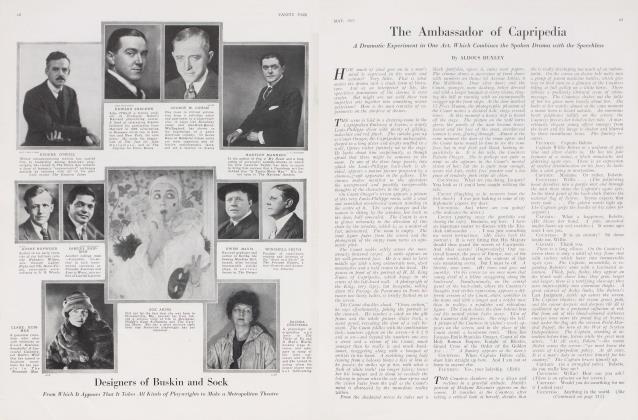

THERE was only one Tragic Turnip at the show of the Society of Independent Artists on top of the Waldorf-Astoria this year. Since the sculpture in the exhibition limited itself to this one jibe at all the traditions of plastic art, it is feared the Independents are becoming unduly sedate and fearful prospect 1 academic. matter of fact, those who went to the show to see freak art this year stood a good chance of remaining to pray at the shrine of the conventional. For with its increasing years the Independents society is unconsciously growing more conservative, in propertion as it is showing work which is better, particularly in the matter of technical achievement.

The critic who went adventuring for masterpieces, watching his soul mean while to note its reactions, had a wide range to cover at this particular dis play, for it was three times bigger than any regular exhibition of the National Academy. To satisfy those fond of facts, it is recorded that there were eight hundred, and forty-five works shown-oils, sculptures, pastels, water colours and drawings. And they ranged from an Irish landscape with a figure by the renowned Robert Henri to a group of drawings of religious subjects by the eleven-year old Marie Kempton -Robert and Marie both being strictly academic in their wprk.

It is always show the reward of the Independents show to find some original expression, sometimes naive, again personal and lovely in colour or design. Toshi Shimizu's In Chop Suey was one of these experiences in naivete, his picture being appalling in its realism, a slumming adventure in itself. Blanche Lazzell's Roofs was another gratification, for its exquisite glowing colour and its very personal way of looking at a cluster of rooftops down Provincetown way.

ONE of the trio who has contributed most to the success of that sublimated Russian vaudeville entertainment, the Chauve Souris, is Nicolas Remisoff, who designed its exotic decors and the weird and fascinating costumes the performers wear. The exhibition of his original designs for these, on view in the Wildenstein Galleries, has been adding to the gayety of Fifth Avenue just as the performance itself has added a new dish to the theatrical menu of Broadway.

Mr. Remisoff, in common with all designers for the theatre, uses water colour and black-and-white, and has all the bavura and comic spirit of the Russian workers in this field. He is showing sketches for all the costumes worn in The Bat, as the title of the piece has been Anglicized for local use, and for most of the principal scenes,

COLONIAL art and the art of today are joined in unique fashion at the Ehrich Galleries, in an exhibition of portrait drawings by Helen Peale, a young artist who is the great-greatgrandaughter of Rembrandt Peale, and therefore but five generations removed from Charles Willson Peale, his distinguished father. Since the present representative of the family has also chosen portraiture for her field, although the pencil is her medium, it has seemed singularly appropriate to show in conjunction with her work a group of American portraits, three of her famous ancestors and their contemporaries.

Miss Peale is represented by a group of twenty-six drawings which display an assured handling of a difficult medium. Her work, especially in such portraits as those of Mrs. Robert Henri, Arnold Genthe, Hamilton Easter Field and Walter Ehrich, has both strength and delicacy, lightness of touch being combined with refinement of feeling, and added to these is the rare penetra tion which makes the portraitist. In an adjoining room the portraits of Commandant Lewis Warrington and Edward Tilghman by Rembrandt Peale, and that of George Washington by Charles Wilson Peale appeared to great advantage in the Colonial setting which has appropriately been provided for them. There is also an interesting portrait of John Adams by James Peale, another member of the family.

THE Macbeth Galleries, to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of the opening of their gaUeries are showing thirty landscapes by Charles H. Davis, N. A. Although Mr. Davis is most familiarly known for his broad land scapes arched over by drifting cloud forms, pictures that make one feel like dropping work and getting outdoors no matter what happens to one's work, he does not concern himself solely with that gracious convention, as this ex hibition shows.

There is In Early May to drive this feeling to the innermost core of the visitor's being. Its elements are a sloping meadow, some sparsely leaved trees, a river palely blue in the thin, watery light of the springtime, sloping meadow-land and the trees beyond form an inexpressibly delicate colour scheme.

The Springtime is another of these less robustious canvases whose austere charm recalls Keats' line about mel ancholy abiding with beauty. His gaunt New England field with its pale green grass is dotted with trees, as yet with out foliage, that are mauve-colored against a sky of palest blue, the clouds touched with faint rose notes. Its sim plidty is equalled by its exquisite grace of mood.

THERE is no other American artist like Guy Pene du Bois-his kinship is with Daumier and Forain. Yet his art is American and he has mirrored American life as no other artist has.

The exhibition of his recent paint ings at the Kraushaar Galleries through April is brilliant. There is colour, rich and luminous, and there is figure draw ing which Is strong and compelling. He is the master of firm, trenchant line, whose simplicity is laden with sugges tion. These paintings express many moods there is The Lawyers, subtle and illuminating, a striking and power ful nude, and the Portrait of George Moore which was particularly noted by the English critics in Mrs. Whitney's "Over-Seas Exhibition." Then there are those inimitable glimpses of life as he sees it; in which his subjects are just people, of the type who dominate by sheer force of number, whose women are apt to •be vulgar and fatuous and whose men are well fed and sleek, yet both of whom are so human as not to be altogether un likable.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now