Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

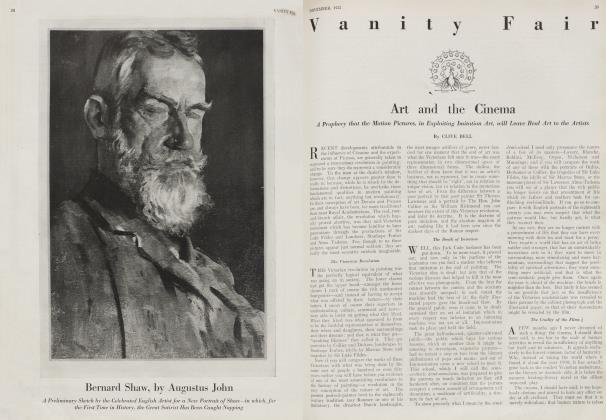

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Art of Augustus John

CLIVE BELL

An Essay in Which the British Painter's Gifts are Considered and Candidly Discussed

"MY sole excuse—no very good one, when you come to think of it—for writing disobligingly about the art of Mr. John, is that I was one of the first to admire it: there is, of course, that other excuse of my having been asked by the Editor to write something, but those who respect the profession of letters never mention things of that sort.

It must have been very early in the nineteen hundreds, at the New English Art ' Club, which, if I remember right, then held its exhibitions in Deering Yard, that I first saw a screen of his water-colors. I was duly enthusiastic; while, needless to say, all the great English critics and amateurs who are now professors and directors of galleries and, for the most part, noblemen to boot, and who all now consider John the greatest painter alive— if not the greatest that ever lived—screamed in rage and unison.

On a very small scale, it was a rehearsal for that grand chorus of abuse which burst over the Grafton Galleries in 1911, when Sir Claude Phillips and Sir Philip Burne-Jones, Sir Sidney Colvin and the poet Binyon (both of the British Museum), Mr. Humphrey Ward and Prof. Tonks, Mr. Konody, Mr. Finberg, Mr. Aitken, Mr. Ricketts and Mr. George Moore, all those, in fact, who now direct the national taste and are taken seriously, for all I know, in America, screamed at the tops of their not very melodious voices that Cezanne and Van Gogh had no talent at all, that any school child could do as well, and that Matisse, Picasso and Derain were either wretched practical jokers or feeble-minded dipsomaniacs. It may have been in the year 1908 that I caught a bunch of these quidnuncs, at a private view of drawings, tumbling ecstatically over each other to buy the works of Cole, the milkman, who, like so many Slade students, had been taught by Professor Tonks to make Michelangelos quite good enough for directors of public galleries.

"The Infant Pyramus"

A GROUP of very charming drawings by John—brush drawings in his best manner —which these same experts would now assure you were worth thirty or forty guineas apiece— went quite unnoticed except for an occasional scholarly jest: I bought a couple for a few pounds.

All this boasting is to show that if I cannot share the patriotic enthusiasm of my betters for what John is doing now, at least it is not on account of any inveterate prejudice: also, I want to prepare you for the announcement that at about that time I bought a very large oilpainting by John, The Infant Pyramus, which was, I believe, the first large picture he ever sold, and certainly the first I ever bought. It is now in the johannisberg gallery; but I lived with it for half a dozen years, so I must be allowed to have given some attention to the subject on which I am writing. The Infant Pyramus and The Way Down to the Sea (which was shown, I think, in the following year) are, in my judgment, the two best pictures Mr. John ever painted. For me, they mark the summit of his career.

What were the qualities that made this early work remarkable? A prodigious natural gift was the best. Painting came to John as singing comes to some Italian tenors; he found he could do what he liked, and he did it with superb ease and gusto.

"He lisped in numbers, for the numbers came ", mightaptlybesaid of John's early work.

This natural painting gift, accompanied by a rather too facile sense of beauty, is by no means rare in England: among the moderns we have Burne-Jones, Watts, Millais and Conder, all painters born. Unlike most, John had the sense to take his gift to Paris, where it came under the influence of Puvis de Chavannes and Picasso. From Puvis he learnt to decorate; to compose in large, flat lints, and to give gesture an almost Poussin-like dignity. From Picasso he learnt far more important lessons, which unluckily he made haste to forget: he learnt to submit, to some extent at any rate, temperament to intellect. He learnt to eliminate by simplification what was superfluous, and he learnt that much of what, to most people, appears essential is superfluous. He learnt that detail atlds nothing to intensity; that only concentration can do that. He learnt that the significance of a work of art is increased by being compressed into a minimum of forms; and that spaces are as significant as lines. And, for a moment, he profited by the lesson. He learnt what were the principles of great art, and these instructions brought out the best elements in his talent.

Certainly in The Infant Pyramus and The Way Down to the Sea, and in his early drawings, there is more than a trace of all that John learnt in Paris. They bear marks of a discipline which has been imposed upon a gift: and this gift you feel in every gesture that the artist makes with a brush in his hand, or without, for that matter. You cannot talk to him for five minutes without becoming aware that he is a greatly gifted being; how much more manifestly, then, will this gift of his appear in the ease and confidence with which he sweeps an arabesque. Also, this gift is all, or almost all, that remains of preciosity in his later work. This he cannot lose; you are aware of its presence when he walks the street. If ever man was born an artist,that man is Augustus John.

Yes, John has a great talent for painting and a natural sense of beauty, both of which gifts are less rare in England than is generally supposed. Unluckily, he has two more national characteristics— intellectual laziness and a propensity to find literature in everything. He makes an arabesque with so magnificent a gesture, that it seems pernickety to bother about whether it expresses what he wants to express, or whether, indeed, it expresses anything at all. There, to be sure, sits the model; but to use the model as a means to conception, and to find for that conception a plastic equivalent, takes a deal of hard brain work; and a generously swept arabesque looks appetizing enough. Still, to give complete satisfaction, a statement of some sort about the model, about the sitter rather, there must be; and if the sitter interest him at all, ten to one it is not as a form but as a temperament that he (or she) interests. Though John rarely has a visual, often he has a literary conception; so he will sweep a character for you on to the canvas. Even here, however, his search does not go very deep, not nearly so deep as that of some English painters, Hogarth for instance, has gone.

John's Method of Work

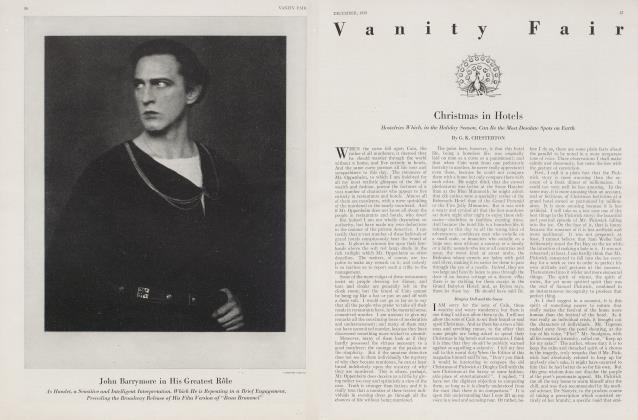

I ONCE had the honor of being drawn by Mr. John: it was at a picnic, after we had drunk I know not how many bottles of Hock or how much old Brandy. The master caught me with what may be, I fear, a characteristic expression on my face, and knocked it off in half a minute on a paper plate. Master, I say, because it is a masterpiece of caricature; here is something characteristic seized and dashed, with a single flick, into a circle of paper. It is a possession to cherish, and cherished it is; for it is the thrilling record, a more or less permanent record—preserved as it is under glass and hermetically sealed—of a miraculous power. It was done literally in less than half a minute on a paper plate; and I cannot help wmndering whether the millionaire who pays—and pays rightly in my opinion—ten thousand pounds (is it?) for a portrait, gets more.

(Continued on page 92)

(Continued from page 49)

Beside this caricature hangs one by Derain of the same unworthy subject. You see at a glance that it is much less amusing and characteristic. Derain, greatly-gifted though he is, has no such natural, unconscious, knack of making a brilliant gesture; no such eye, no such wrist, no such aptitude for catching a likeness and fixing it with a flick of the pencil. But, if Derain were to paint myportrait, or yours, he would produce something worthy to hang beside no matter what masterpiece. Whereas John's caricature contained all, or almost all, that John has to give, Derain's—compared with a finished portrait byhim—would be verymuch What a pocket-book entry byWordsworth would be, compared with the Ode on Immortality or the Sonmt on Westminsicr Bridge. For, between the note and the perfect piece would lie all the tremendous contortions of a master's mind. Do not suppose me insinuating that John has none. He has an uncommonly good mind. But either he does not choose to applyit, or has lost the art of applying it, to painting.

I am by no means surprised or vexed at John's popularity. The sheer bravura of his painting, externalizing as it does a bewildering gift, gives a delicious thrill, Here, in a series of handsomely sweeping brush-strokes, you have the authentic signature of genius to hang in your hall, If that is not worth more to a millionaire than a stcam-y-acht, Fifth Avenue and Mayfair should be ashamed of themselves. Furthermore, what a privilege to sit to such a man—one possessing all the notorious, and quite genuine, charm peculiar to born artists; the distinction, the humor, the intelligence, all bound together in the grand traditional manner by a generous personality. John maynot be a great painter, but he is a great figure: he reminds one a little of Watts, only he is quite without Watts's pomposity, It is not those who have sat to John who have anything to regret or complain of. But we, who recognized his budding talent and saluted its earliest manifestations, mayperhaps be pardoned a sigh, and even a touch of ill-temper, over what has been made of it. We may be parcloned for wondering whether Mr. John, WHO seems sometimes to have read everything, was ever heard to mutter, as he knocked off a brilliant impression of Mr. Lloyd George, or made an inspired grande dame of Madame Suggia, qnalis artifex pereo: or for wondering whether Mr. John thinks ever of the young man of genius, who may, without ludicrous vanity, have dreamed of becoming the English Manet.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now