Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

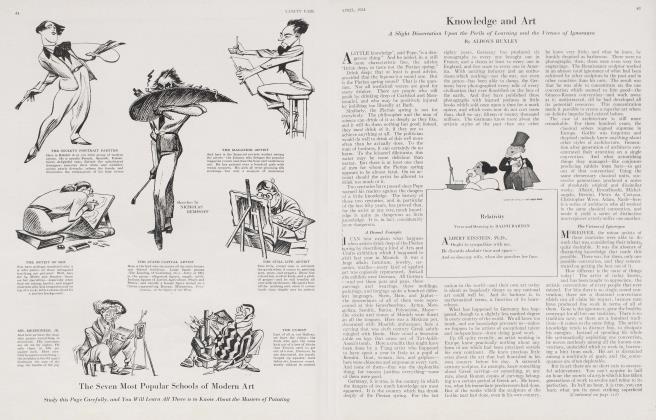

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowModern Art, and How to Look at It

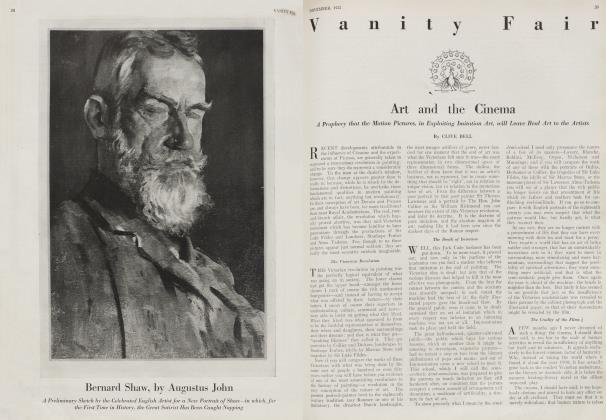

CLIVE BELL

A Critical Appreciation of "The Dial" Portfolio. "Living Art", With Certain Instructive Remarks

IN employing the skill and science of the Mares Gesellschaft to produce an anthology of contemporary art, Mr. Scofield Thayer has deserved well of the Republic of Taste. Notoriously', no anthologist ever quite satisfies any one—not even himself; and Mr. Thayer, in his prettily written preface (how touchingly grateful one is these day's for the least little bit of preciosity'), does his best to forestall criticism by admitting omissions. To be sure, it does seem odd, in a work of this magnitude, to find nothing by Rouault, Friesz, Dufy, Despiau, Utrillo, Marchand, Gris, or Leger; and if he felt that some Scandinavian artist should be included, why prefer Edvard Munch to the incomparably superior Per Krohg?

However, ray chief complaint is on account of sins, not of omission, but of commission. Surely into such fine company—the company of Matisse, Picasso, Derain, Bonnard, and Maillol—it is a pity to drag Ernosto de Fiori, and Alfeo Faggi (than whom I suppose there must be scores of better sculptors in America), and Wyndham Lewis and Boardman Robinson. Certainly, in a collection of this sort, there must be some second-rate work; Chagal is rightly represented. I do not complain of the inevitable mixing of classes: but the Faggis and Lewises go by another train.

HOWEVER, there is much to be grateful for. Stay-at-home Europeans will thank Mr. Thayer for bringing them acquainted with the work of Charles Demuth. When Mr. Derauth has shed the last remnants of Cubism, which is about as useful to his art as the appendix is to the human body, he will be a painter of whom one would wish to see more. And it was clever to discover a Bonnard which suffers so little from reproduction that, as usual, one finds oneself wondering whether, after all, its creator may not be our greatest living painter. Amateurs of contemporary art, you see, will find plenty to interest them in this sumptuous production; but the people who should be most grateful to Air. Thayer are those to whom he here gives a magnificent introduction to the modern movement, in the form of this sumptuous album.

These, if they can (the album, Living Art, The Dial Pubfishing Company, New York, costs S60.00), will clearly be well advised to buy. But, having bought, what are they to do? There are thirty sheets, 25 x 20 inches in size; and a good many people whose walls are not over-crowded will, I dare say, frame and hang them: there is something to be said here for that. And yet, I wonder whether these fine reproductions do not deserve to be taken more seriously. For the moment, at any rate, let us treat them as though they were originals; and, bv merging them in the class "pictures", allow the question to become more general.

We hang our pictures on the wall, mainly, I suspect, because the earliest pictures were painted on walls, partly because we see them so hanging in public galleries. Yet, by hanging them, we— all I mean, but an exceptionally attentive minority—rob them of the best part of their value. Let anyone who doubts the truth of this take down his or her favourite and replace it by a similarly sized and shaped piece of paper, framed, and daubed vaguely in the same colour scheme. Tn a month, he or she will hardly remark the difference: the fact being that most people do not contemplate their decorations, but notice merelv that they are there. So, if you happen to believe, as I do, that there is more in a Corot than in a vaguely daubed newspaper, you will have to agree, I think that, we lose a good deal when we treat a Corot as though it were a daub.

BUT wdiat about "decorative pictures"? To begin with, all pictures which have not been rendered positively repulsive by sheer bad taste are potentially decorative. It is merely a question of position and surroundings. A veiy slight acquaintance with the stately homes of England—and of America, too, I feel sure—suffices to demonstrate that a Rembrandt in mv lord's Jacobean hall is just as decorative as a Matisse in my lady's chamber. A rather closer acquaintance will demonstrate that a manifest copy, or more probably an honest picture by a lubberly contemporary, is just as satisfactory for purposes of decoration as an authentic old masterpiece would be; and that that delicious note of pearly gray above the sofa in the corner of the drawing room— the Lancret fan from the Bon Marche— does its business as adequately as if it were really by Watteau.

(Continued on page 88)

(Continued from page 56)

Obviously, it is wasteful to use first rate pictures for purposes of decoration: besides, there are so many bad or mediocre with which something must be done. Think of all the family portraits! A roving eye, no matter how sensitive, will hardly take in more than surface quality and general disposition; and to get up and peer into a picture is very unsociable, and perhaps not very profitable in the thick of general conversation. Yet, as everyone who cares seriously for visual art knows, the only way in which one can get at the significance of a picture is by peering into it, by attending it as one attends a poem or a piece of music. And, except in public galleries, which have inconveniences of their own, one can rarely attend to pictures hanging on walls.

PAINTERS understand this: they show their works one by one, setting them on the easel. Unfortunately, in studios, one is apt to^feel so much embarrassed by the presence of the artist, so anxious to say the right thing, so bent on saying something, that the best part of that energy which should go into appreciation and comprehension is drawn oil into making oneself agreeably sympathetic. It is a little better at the dealer's: there it is a little easier to retreat into that corner of oneself which reacts to painting. But even at the dealer's, one is harassed by a sense of obligation; one feels bound to give the impression either that one may be going to buy oneself, or—if that is manifestly out of the question—to persuade someone richer to buy. A small public gallery can sometimes be delightful; but the malaise, the heavy inhibition, which too often overcomes us as we enter the great national collections, is a familiar and constantly recuring affliction which requires, and will some day get, I hope, I careful analysis.

The conditions necessary to the perfect appreciation of pictures seem to me to be these: (a) that the pictures should be exhibited one by one on an easel; (b) that, though comment should not be discouraged, it should not be expected: (c) that the spectators should have come together expressly to look at pictures, not to do something else and look at them incidentally, between dances or on the way down to dinner: (d) that smoking should be permitted. If I am right, the best way of seeing pictures would be in a private house at a "picture party".

But we live in a self-conscious age. There are few things anyone cares for less than being called "high-browed", "intense", "aesthetic", "esoteric", or "highfalutin'";and anyone who ventured to give the sort of parties I am thinking of would quite certainly be called them all. Were the Editor of Vanity Fair to receive, with tomorrow's tea and toast, the following note:

"Cher ami:

I have got Arthur Rubinstein next Thursday. Do come. Dinner 8.30; black tie.

A bientot, DOLORES"

he would think nothing of it—nothing, I mean, but well and fair. He would go to the party, meaning to listen to the music: it would not be thought bearish in him to sit in silence next a charming lady while Mozart was being played; quite the contrary: and so he could give himself up to his aesthetic emotions as completely as if he were reading poetry at home. Now, suppose him opening this, "My dear Mr. Crowninshield,

I have just received from Parks three works by Bonnard, and I want you and a few people who really care for pictures to come and enjoy them tomorrow about noon, when the light is best. I hope you will stay to lunch.

Yours very sincerely, XANTIPPE P. BECK"

What will be his first exclamation? "Precious", at best; "pretentious", more probably; possibly "silly little fool". That way, however, perfect appreciation lies. American hostesses are notoriously the bravest in the world. And The Dial Portfolio gives even those who cannot afford three Bonnards a chance.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now