Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

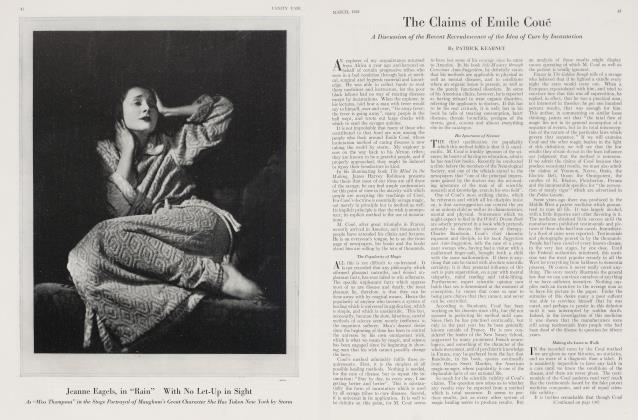

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Theatrical Callboard

Critical Notes Before the Curtain Rises

KENNETH MACGOWAN

PEER GYNT was written in Rome and a velveteen jacket. A Doll's House sprang full-armed from a silk hat bought in Munich ten years later. Italy and the velveteen jacket are more important than the date (1867) in fixing the nature of the extraordinary and monstrous play which the Theatre Guild is reviving.

It would be interesting to know whether Ibsen brought the velveteen jacket with him from Norway. Had he risked wearing such badge of freedom in that chilly and Puritanical clime where flourished the Helmars whom he later loved to castigate? In Norway he had been a bit of a Wunderkind—director of the Bergen Theatre at twenty-three, manager of the National Theatre in Christiania six years later. The plays that he wrote for those houses were sad stories of the death of kings, poetic romances of legendary heroes that the Scandinavians have always loved. Probably, in the fierce, uncompromising idealism of youth, he wore a horned helmet and chain gauntlets while he was writing The Vikings at Helgeland.

Rome found Ibsen launched on a new sort of play. New for him, at least, though it really dated back to Goethe's Faust. It was a rambling and Gargantuan poetic narrative. Fantasy, philosophy, ironic humor played over it as Peer shot down the years from boyish huntingjacket to frock coat and silk hat. His other philosophic poem for the stage, Brand, belongs to Rome and the velveteen period, and there are those who find more in the positive faith of this play —"replete", as a German critic quaintly described it, "with the catagorical imperative"—than in the nay-saying of Peer Gynt. Yet it is Peer Gynt that is acted up and down Germany every year, and even in Paris and New York, while Brand lies neglected.

Mansfield, and Schildkraut

TF the Theatre Guild had been patient enough to wait five years it might have celebrated the centenary of Ibsen's birth by its production of Peer Gynt. In that case, however, there would not have been so youthful a Peer for the opening scenes. The part is played by Joseph Schildkraut, the Liliom of Molnar's play, and Schildkraut is now twenty-six. It is amusing to reflect upon the extraordinary

difference in the ages of the two Peers who have presented the play to America -almost as great a difference as in the first and the last acts of the play itself. When Richard Mansfield produced Peer Gynt in x~o~ he was in the last year of his life-just past fifty. Mansfield-like most of the players who have done the partwas compelled to simulate both youth and great age. Schildkraut, almost alone, plays the young Peer with the natural conviction of youth, and falls back on the make-up box for middle age and senility. Not a bad arrangement, if a young player can muster the practice as well as the genius of an old one. Schildkraut, having played in German repertory theatres for a bare ten years, has had plenty of prac tice-parts by the score, ranging from Romeo to the Button-molder in Peer Gyni.

The Theatre Guild presents Peer Gynt just sixteen years after its first production in America and fifty-six years after its completion by Ibsen. It was only in the playwright's early life, when he was the director of a playhouse, and in his later years when he was a famous figure in the whole European theatre, that his plays were given within a season of their composition. Love's Comedy had to wait ten years for production; Brand, twenty years; Peer Gynt, ten; The League of Youth, thirty. It is interesting, by the way to note from William Henri Eller's book, Ibsen in Germany, that Chicago and not his native Norway nor his adopted Germany, gave the first performance of his most debated play, Ghosts, and that it was London—through the agency of William Archer and the London Stage Society—which first brought to performance each of his last four plays.

The'Guild is using the translation of Peer Gynt by this same Archer, who did more than any one to make Ibsen as widely known in America as—say, The Green Goddess—though hardly so popular. It was Archer, by the way, who was pictured by the incomparable and highly dangerous Max Beerbohm in audience with Ibsen in a, room whose wallpaper was liberally patterned with the famous hair and whiskers of the Norwegian. Archer, who has come to America for the premiere of Peer Gynt, is rumored, incidentally, to have another original play in his steamer trunk.

{Continued on page 106)

(Continued from page 10)

From Sacha Guitry

ACHA GUITRY is principally known to New York through Sleeping Partners, Deburau, and his father's fear of the ocean, which has kept the Selwyn's from fulfilling their desire to exhibit on Broadway the talents of Lucien and Sacha as actors. Before the year is out, David, Belasco will produce the long-promised piece, The Comedian, for Lionel Atwill, and Henry Miller will appear in the grave and exalted, as well as short and woman-less, drama, Pasteur, under the management of Charles Frohman, Inc.

News comes from Paris of a new play by Guitry, Un Sujet de Roman. The subject, apparently, is an inhabitant of the ivory tower, one of those literary men who plod steadily ahead for forty years writing what must be written and not what the public wants. At the end of the forty years his wife is still oblivious to the fact that he has won the respect of the greatest writers of the world. She forces him to sign a contract with a publisher of sensational fiction. At this point there intervenes a convenient paralytic stroke. The wife taking advantage of his illness, turns over a half-finished manuscript to a newspaperman with instructions to finish it in popular fashion, writes asking for him the Legion of Honor, and seems quite on the point of wrecking his career. Again with a convenience rather foreign to Guitry's other work, the man recovers his capacities and manages to undo the mischief. Following the best examples of the higher literature, he pardons the wife. They live on in a happier state of connubiality since she has found in his desk letters from the greatest of the literary world calling him "Master". It is the elder Guitry, of course—greatest actor of France today—who dictated the creation of such an aged hero and who succeeds in meeting the difficulties of the part.

Varying Prospects

AT the moment of writing it is a question when or whether William Gillette will come into New York with revivals of Sherlock Holmes and of Barrie's Dear Brutus. Certainly he will tour up and down the country with the two favorites, just as he did ten years ago with a repertory that included Held by the Enemy, Secret Service, The Private Secretary and Too Much Johnson, as well as the detective drama. It is a heartening sight to see an actor of seventy—a frail man, too—who not only canters off in harness but double-harness at that. Many talk of repertory; in fact no actor or actress feels himself quite respectable who does not admit that the future of American acting—and American playwriting, too, for that matter—lies with the founding of repertory theatres. But who except a gray-beard like Gillette has the courage to do something about it? I don't want to imply that a season of Sherlock Holmes and Dear Brutus, played by a single company, is a panacea for the American stage. But here is one kind of proof that repertory is possible if it is backed by reputation and courage.

Some day, of course, Laurette Taylor will appear in repertory. But until this season it looked as if the repertory would be confined—like the repertory of Sothern and Marlowe—to a single playwright. And not William Shakespeare. This year, however, Miss Taylor comes forward, for the first time in a dozen years, in a play not by her husband, Hartley Manners. It is Humoresque, made by Fannie Hurst from her own short story. Whether you like it or not, the author of its being is the motion picture. If it hadn't been for the great success which the story won upon the screen, Miss Hurst would hardly have thought of dramatizing Humoresque. Also, if it hadn't been for the remarkable performance which Vera Gordon gave of the mother, I do not imagine that Miss Taylor would have been spurred on to play her first middle-aged part. Failing Matthilde Cotrelly, the interested management would have bidden Margaret Wycherly cultivate a Yiddish accent. As the play has been fashioned, it dodges politely and wisely the issue of the happy ending which the screen tacked on to the poignant story of the young violinist from the slums seized and shattered by the war.

Another dramatization headed for Broadway is Rita Coventry, which Hubert Osborne, author of Shore Leave, has made from the novel by Julian Street. Brock Pemberton is the producer.

The first play to come from Porter Emerson Browne since he wrote The Bad Man is Ladies for Sale, a piece that takes war-shattered Vienna for its point of theatrical departure.

Magic makes a trinity with melodrama and mystery in Zeno, a play by Joseph F. Rinn designed to exploit some of the many deceptions practiced by the gentleman with no cuffs to deceive. It is to be produced by Lee Kugel with two infrequent—in fact two too infrequent—players in the leading parts, Effie Shannon and George Nash.

Among the impending productions of Sam H. Harris is a new drama by Owen Davis cast in the serious mould of his The Detour. This is Ice-Bound, and it is an easy guess that the locale is not Long Island this time but somewhere north of New Bedford. Robert Ames, so fine in The Hero, heads the list of players.

When the Washington Square Players mounted that powerful little tragedy The Clod few except those who knew the prejudices of American managers would have imagined that it would be half a dozen years before a full-length play by Lewis Beach would come to Broadway. The title of his new piece, The Square Peg, suggests tragedy again, but Guthrie McClintic, having swallowed Gringo, is not one to strain at a play without a happy ending.

Margaret Anglin speaks so highly of The Sea Woman as to raise the question whether she will bring it into New York this year with half the season already gone; but the road is not what it used to be and Broadway is always hospitable to Miss Anglin. The author of her new vehicle is the excellent actor and occasional collaborator, Willard Robertson.

Back from the movies comes Frank Keenan in Peter Weston, a play by Frank Dazey, son of the author of In Old Kentucky, and Leighton Osmun.

Charles Richman contemplates a return to the stage in a play by Charles Richman called Suspended Sentence.

Bookshelf Repertory

IN spite of Arthur Hopkins and Ethel Barrymore, the bookshelf continues to house America's only repertory theatre. There, no matter what the evening, you will find some good play, old or new, ready to entertain you. Play-publishing was once deemed as risky an occupation as establishing an art theatre, but now the presses grind out dramas steadily and profitably. Consequently, you may go to your bookseller and purchase seats from Doran for a departed success like The Harp of Life by Hartley Manners, or from Stewart Kidd for that interesting failure, Goat Alley, by Ernest Howard Culbertson. You can sit again through Owen Davis's The Detour, thanks to Little, Brown, and, if you were disappointed with the Theatre Guild's performance of Georg Kaiser's expressionist drama, From Morn to Midnight, you can remount the play with the aid of your imagination and Brentano.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now